For the first time ever, a virus has been observed attaching to another virus. However, the never-before-seen behavior was almost missed after it was stumbled upon in a happy accident involving some anomalous sequencing results.

“When I saw it, I was like, I can’t believe this,” Tagide deCarvalho, first author of a study announcing the discovery, said in a statement. “No one has ever seen a bacteriophage – or any other virus – attach to another virus.”

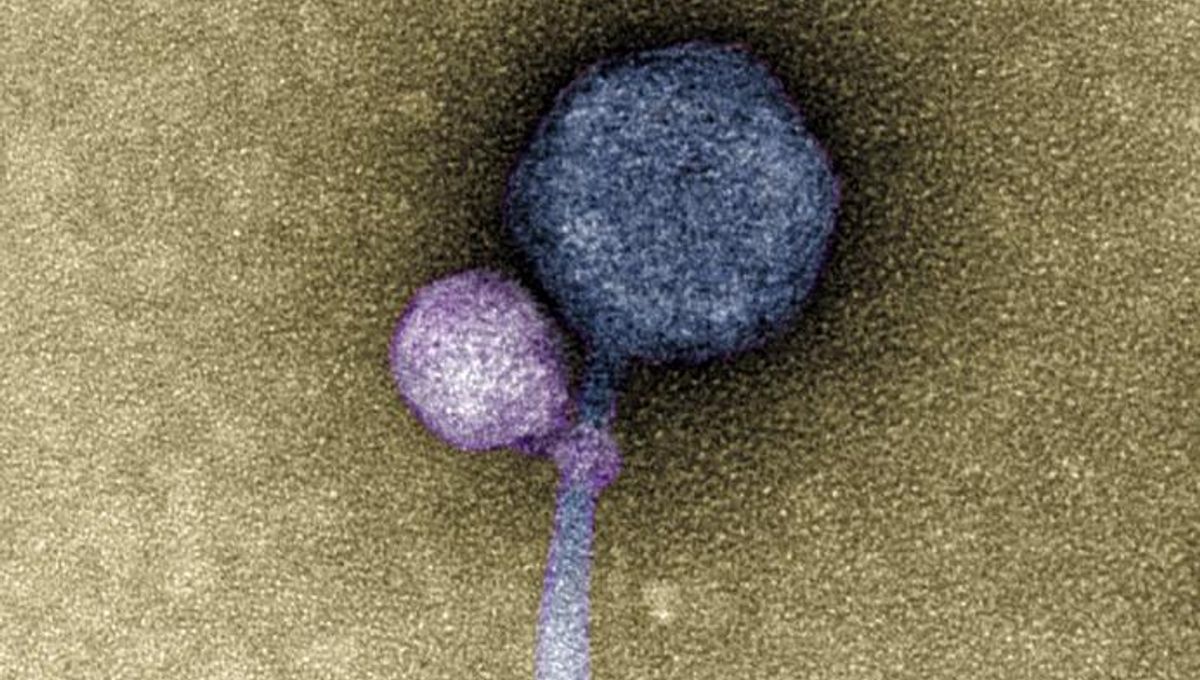

The virus in question is a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria – and also a satellite virus, which relies on other, “helper” viruses to complete its life cycle. Satellite viruses lean on their helpers either when building their capsids – the protein shell of a virus – or when replicating their DNA, both of which require the two viruses to be close together. Now, the new study suggests that they go a step further, getting up close and personal by latching on to their helper virus’s “neck” – the place where the capsid joins the tail of the virus.

But the groundbreaking discovery almost didn’t happen at all. A group of undergraduates were analyzing the sequences of bacteriophages from environmental samples when they found what they believed to be contamination in the sample. The sequence of the phage they were studying was present, but so was a smaller sequence that didn’t map to anything the researchers knew.

Repeating the experiment suggested that this was no mistake, and electron microscopy imaging later revealed the presence of helper viruses, 80 percent of which had a satellite bound at the neck.

Spookily, some of the helpers that were unencumbered by satellite viruses still had remnants of past attachments at the neck, which senior author Ivan Erill likened to “bite marks”.

The researchers were also able to analyze the genomes of the vampiric viruses, as well as their helpers and hosts, finding that most satellites have a gene that enables them to integrate into the host cell’s genetic material.

However, this is not universal. In one sample, the satellite, which has been named MiniFlayer, is the first known case of a satellite with no gene for integration. It, therefore, must stay close to its helper, MindFlayer, when entering a host cell, the team hypothesize.

“Attaching now made total sense,” Erill said, “because otherwise, how are you going to guarantee that you are going to enter into the cell at the same time?”

Further bioinformatics analysis hinted that this interaction between MiniFlayer and MindFlayer could be ancient, with the two co-evolving for at least 100 million years, according to Erill.

The team hope their findings will inspire future work into the unexpected phenomenon to further our understanding of it and perhaps explain some strange phage sequencing contamination.

“It’s possible that a lot of the bacteriophages that people thought were contaminated were actually these satellite-helper systems,” deCarvalho added, “so now, with this paper, people might be able to recognize more of these systems.”

The study is published in The ISME Journal.

Source Link: Virus Seen Latching On To Another Virus (Like A Tiny Vampire) For First Time