The Sun is the closest star to us and the most studied by humanity. There is a lot we still do not know about it. Among the unknowns, until today, were the Sun’s polar regions. We simply had not seen them before. Now, the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter has delivered our first-ever look at the Sun’s South Pole.

It might seem peculiar: the Sun is right there! How have we not seen its poles? The answer rests in celestial mechanics. When we send something into space, it carries the momentum of our planet around the Sun, so it has its speed and it is roughly in an orbit around the Sun’s equator. Not the right spot to see the poles.

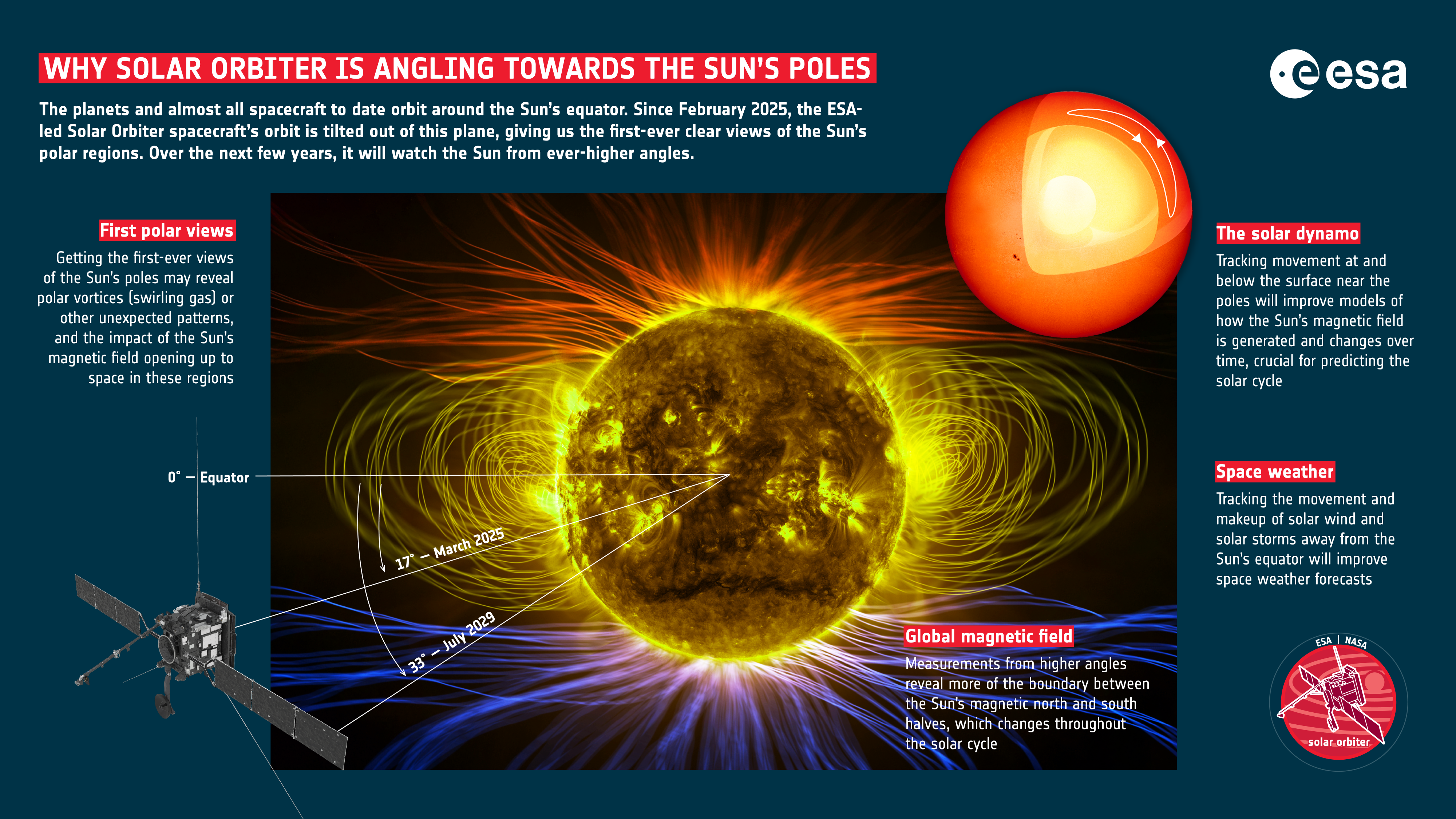

For a spacecraft to get close to the Sun, it needs to lose the excess orbital velocity that comes from being from Earth. That is achieved with rockets and gravity assist maneuvers, using the planets as a brake. In the same way, it is possible to shift the angle of the orbit, and Solar Orbiter used a flyby of Venus earlier this year to climb to a 17-degree tilt with respect to the Sun’s equator. The result is that it has been able to give us the first-ever look at the Sun’s poles.

“Today we reveal humankind’s first-ever views of the Sun’s pole,” Professor Carole Mundell, ESA’s Director of Science, said in a statement sent to IFLScience. “The Sun is our nearest star, giver of life and potential disruptor of modern space and ground power systems, so it is imperative that we understand how it works and learn to predict its behaviour. These new unique views from our Solar Orbiter mission are the beginning of a new era of solar science.

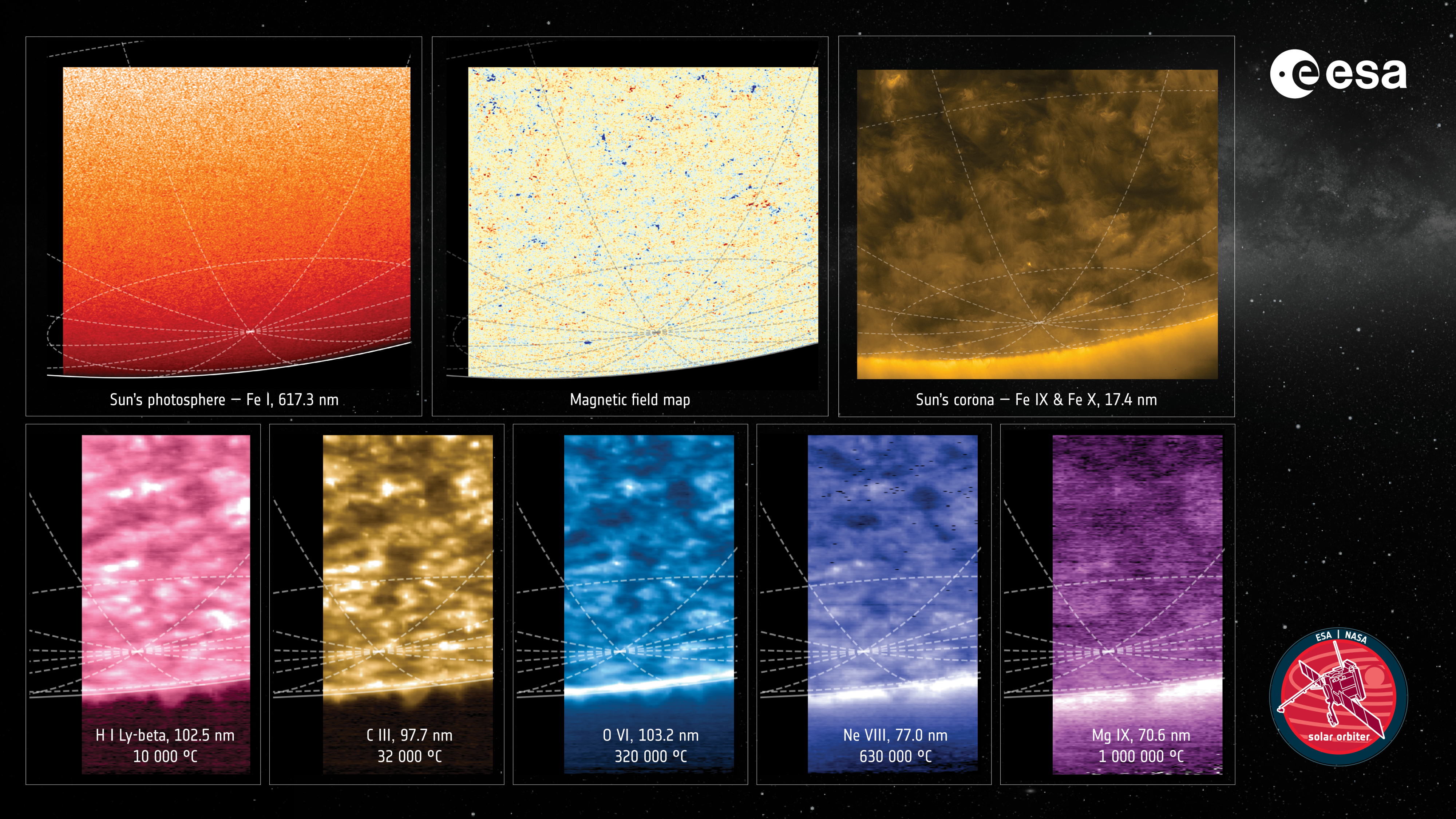

These images are from the very first observations, with Solar Orbiter snapping them and measuring different properties while at 15° below the solar equator – not even at its current tilt. The images were taken by the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI), the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), and the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument. Each is studying different properties of the Sun: the visible light emission and magnetic field (PHI); its extremely hot corona (EUI); and the various charged gases above the Sun’s surface (SPICE).

“We didn’t know what exactly to expect from these first observations – the Sun’s poles are literally terra incognita,” added Professor Sami Solanki, who leads the PHI instrument team from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany.

Different views of the poles through different instruments.

Image credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/PHI, EUI & SPICE Teams

The full pole-to-pole observations dataset will be released in October, with all 10 Solar Orbiter instruments delivering science, as well as photos, from the North Pole. The mission will use future encounters with Venus to raise the tilt even more. In December 2026, the tilt in its orbit will increase to 24°, and from June 10, 2029, the spacecraft will orbit the Sun at an angle of 33°.

“This is just the first step of Solar Orbiter’s ‘stairway to heaven’: in the coming years, the spacecraft will climb further out of the ecliptic plane for ever better views of the Sun’s polar regions. These data will transform our understanding of the Sun’s magnetic field, the solar wind, and solar activity,” explained Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter project scientist.

Solar Orbiter is conducting a new kind of study of the Sun.

Image credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter

Solar Orbiter has been revolutionary in our study of the Sun, especially as our star is currently experiencing the peak of activity for this solar cycle – the solar maximum.

Source Link: Watch: First-Ever Footage Of Sun’s South Pole Gives Spellbinding New View Of Our Star