What do you get when you combine a team of scientists, a jet of crystals, a giant laser beam firing X-rays, a synchrotron facility in Japan, and a ticking clock? New short film Crystal Hitters: Beamtime, following a group of scientists from the University of Connecticut and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, reveals just that, shining a light on the scientists behind scientific experiments, and the very real emotions that go into their work.

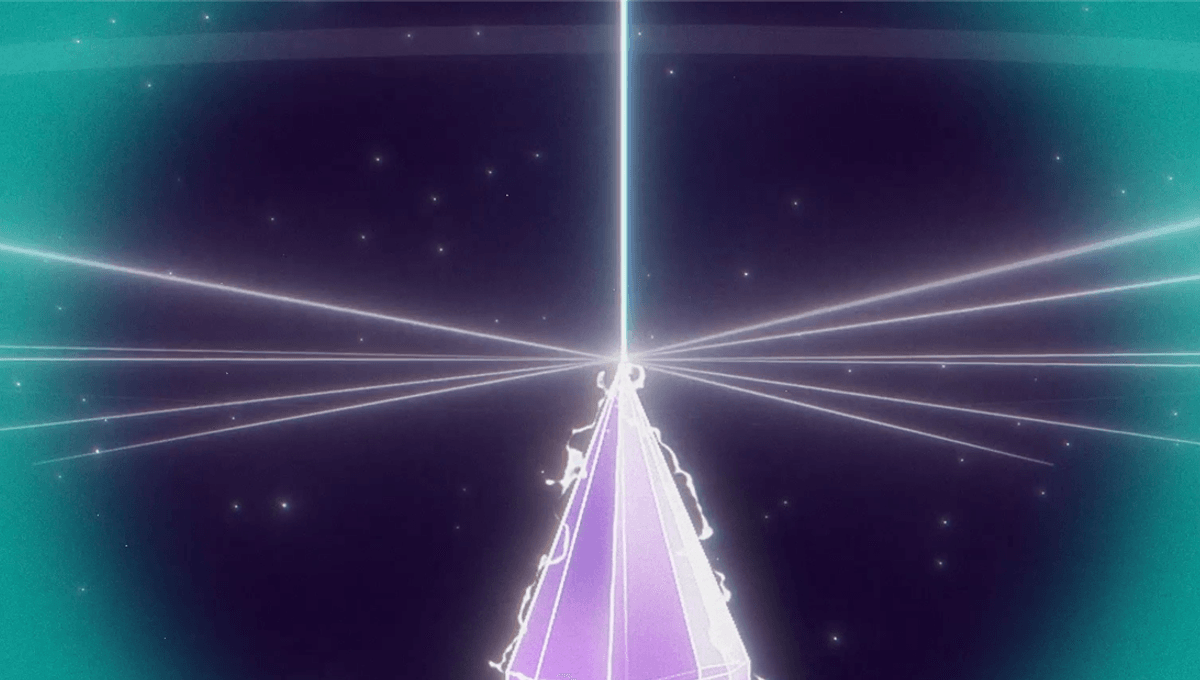

The team traveled to Harima Science Garden City’s synchrotron facility to use the SPring-8 Angstrom Compact free-electron LAser (SACLA) X-FEL laser – a cutting-edge tool that combines the properties of X-rays and lasers to produce intense, focused X-ray beams – but there’s a catch. The team had been awarded just 60 hours of “beam time” and once the beam goes on there is no turning back.

Over the course of the five-day experiment, we follow the team as they attempt to place jets of liquid crystals into the X-ray beam created by electrons traveling at nearly the speed of light. Working in round-the-clock shifts of around 10-12 hours, everything must be aligned perfectly to reach the goal they’ve all been working towards: a crystal hit. Using the crystals and the beam in this way is a pioneering new technique developed by the team and carries a lot of challenges, both mentally and physically, for the researchers.

Every single aspect of this experiment is challenging. Getting the crystals prepped and into the beam, ensuring we are hitting crystals, processing the data. Every part has new challenges that affect each part of the team differently.

Dr Aaron Brewster

“Every single aspect of this experiment is challenging. Getting the crystals prepped and into the beam, ensuring we are hitting crystals, processing the data, and solving the structure,” Dr Aaron Brewster from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory told IFLScience.

“Every part has new challenges that affect each part of the team differently, but we work together and have made progress on all of them.”

When the X-ray beam strikes the jets of liquid crystals, this causes diffraction. This diffraction is known as a crystal hit. The system then takes a rapid series of photographs, as many as 30 per second, of the crystal structure. Not all of the data is useful though, as sometimes there might not be a crystal hit.

“There’s a lot of steps to go from ‘this is a hit’, to ‘this is data we can use’,” explains Dr Daniel Paley from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the film. These photographs help the scientists to solve what they describe as a “logic puzzle”, finding the crystal structure that has been created. Combining the photographs and data allows the team to figure out where the atoms are within the crystal.

“Our goal is to solve many structures to build up a suite of possible materials to investigate. When we can find common properties, we can hopefully begin to predict how to alter them to get new properties and design towards the most useful materials,” continued Brewster.

The way people work together is a really powerful part of the scientific process.

Dr Nate Hohman

The team was successful in capturing new crystal structures caught in the images. The applications for these structures are, in theory at least, limitless, and the team has high ambitions for what could be achieved using them. “We’re making new stuff,” says Dr Nate Hohman from Berkeley Labs in the film. From structures to help with carbon sequestration, to those that could work on future space missions, to the dream of cheap renewable energy, the passion for the potential of what could be achieved shines through.

“Over that year we did three X-FEL experiments and, combined, collected enough data to solve 10 new structures. This exceeded our expectations and encouraged us to continue building up the method to solve more structures, faster!” concluded Brewster.

The film is also about communication, not only within the team in Japan but also through the film itself, helping to expose those not in the field to the scientists behind the science. During the experiment, they experienced issues with the line, the machine, and the network that feeds the liquid crystals into the beam itself. “When the beam comes back on you can start your experiment again, you don’t get any time back,” explains Hohman.

The crystals might be 3-hydroxy-bio-phenol, but they are nicknamed by Masha Aleksich as the “marshmallow samples” because they resemble tiny marshmallows in the images. It’s moments like this during the short film that help connect the audience to the science and scientists themselves. “The way people work together is a really powerful part of the scientific process,” said Hohman.

There is also the rise of new technology such as AI, which the team hopes to train to recognize the crystal structures. They simply need enough crystal hits so the AI can learn what they are and eventually even predict what could be possible.

“What the AI will do is take the solved crystal structures, the chemical composition of the crystals, and the properties of the crystals, to tell you which chemical elements to combine in given proportions to create a structure with desirable properties. The team needs to collect enough data from enough compositions in order to train the AI,” Dr Laura Leay, science consultant and co-producer for the film, told IFLScience.

Solving the problems mentioned in the film might seem a long way away for one group of researchers, and maybe it is. However, as with any team, it is their dedication, hard work, and perseverance that will lead to the crystal hits of the future.

Crystal Hitters: Beamtime has been selected and screened at the Max Sir International Film Festival in Costa Rica.

Source Link: Watch Groundbreaking Science In Action With Short Film "Beamtime: Crystal Hitters"