Attempting to model astronomical systems can often involve supercomputers, but scientists have also looked for alternative analogue systems to model the astronomical systems they are studying. This can involve varying degrees of complexity. In the past, they have simulated black holes in the lab using “quantum tornados” inside superfluid helium, but even old-fashioned water has been used to create “water black holes“, serving as a useful analogue for the real thing.

Now, researchers at the University of Greifswald and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany, have shown that water tornadoes can also provide a surprisingly good analog when studying planetary formation.

The protoplanetary disk model was predicted long before we got the first spectacular images of other early planetary systems. Over the last decade, astronomers have imaged hundreds of protoplanetary disks that will go on to form exoplanets in a process that can last 10 million years or longer.

But there are plenty of mysteries still to solve about planetary formation, and new ones are uncovered as our telescopes and methods become more advanced. For example, it may be that protoplanetary disks are a lot smaller than we expected.

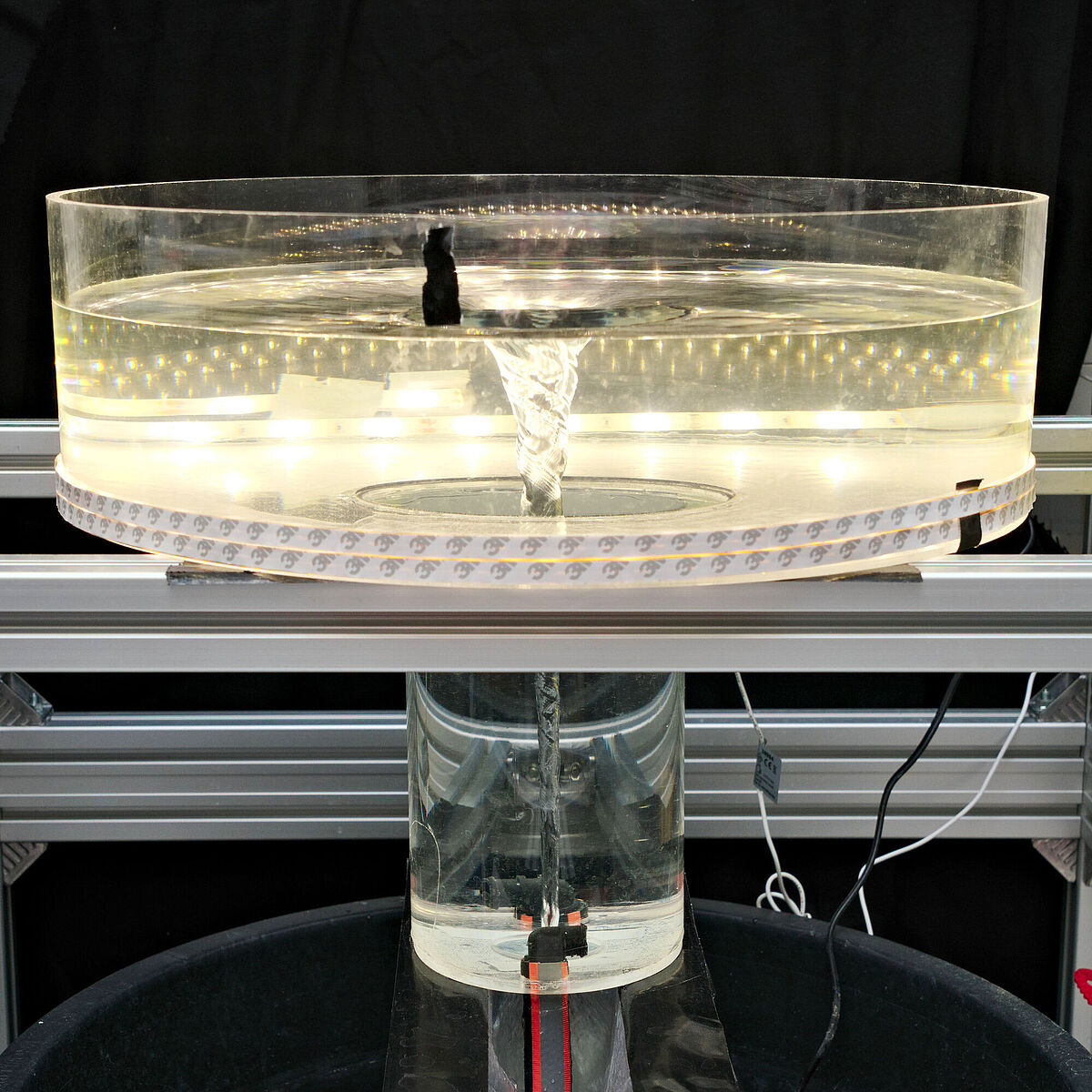

In a new experiment, researchers attempted to model protoplanetary disks using a water tornado. This has been attempted in the past, but in a new setup, the team was able to simulate a wider distance from the analogue star. At the bottom of the tank, made of a wide cylinder on top of a thinner cylinder, the team used nozzles to pump water in opposite ways to create a vortex.

With the new design, the usable area to simulate a gravitational field began around 3 centimeters (1.2 inches) from the center, and stretched all the way out to the edge. The team then placed polypropylene beads into the tank, to represent gas and dust within a protoplanetary disk. These were chosen because their density is similar to water, meaning that they would stay near the surface and also be dragged along by the rotating water. The researchers then filmed the beads using a high-speed camera, keeping track of their positions, while an algorithm was used to calculate their trajectories.

The tank setup.

Image credit: S. Schütt (University of Greifswald)

The team found that the setup worked surprisingly well.

“The motions and flows closely resemble those observed in planet-forming discs and planetary systems,” Stefan Knauer from the University of Greifswald said in a statement.

In fact, the team found that the particles within the tank were described well by two of Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. The first law – that each planet’s orbit is an ellipse with the star at the center of one of the two foci – was not obeyed in this experiment, with particles taking a circular path on average. But the second law and third law were, overall, good descriptions of the particles inside the tank.

The second law states that “the imaginary line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps equal areas of space during equal time intervals as the planet orbits”. Essentially, as a planet’s orbit is an ellipse, this means that planets must move faster when they are at perihelion (closest to the Sun) and slowest at aphelion (furthest away from the host star). The third law states that “the squares of the orbital periods of the planets are directly proportional to the cubes of the semi-major axes of their orbits”, and implies that the orbital period for a planet gets rapidly longer as you move away from the host star. For instance, Uranus takes a lot longer to go around the Sun than Mercury.

According to the team, the particles were able to mimic protoplanetary disks closely, with particles acting similarly to dust grains in real environments.

“The set-up has many advantages: it is easy to realize a large ratio between inner and outer radius and thus to study global dynamics, in contrast to local shear flows as in previous experiments,” the team wrote in their study. “It is diagnostically very accessible. It is very cheap to build. It is possible to determine dimensionless quantities such as the Reynolds or Stokes number and analogue quantities such as the central mass.”

“The current results from this analogue experiment are impressive,” Mario Flock, who leads computational studies of planet-forming disks at MPIA, added in a statement. “I am confident that, with a few modifications, we can refine the water tornado model and bring it closer to scientific application.”

“We hope this new analogue experiment will offer insights into how processes unfold across vast distances within planet-forming discs.”

The study is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters.

Source Link: Water Tornadoes Are Surprisingly Good At Modeling Planetary Formation