The length of an Earth day is built deep into our sense of time, so much so that minuscule variations in the Earth’s rotation can create considerable problems. How then are we to operate on other worlds, where the length of a day is completely different? The European Space Agency (ESA) doesn’t have the answer, but thinks the time has come to ask the question, before future lunar bases find themselves saddled with a clock that doesn’t suit their needs.

Lunar missions, whether crewed or robotic, have operated on the times of their home base. That’s worked well enough because no one has stayed long, and missions haven’t interacted. A future Gateway station with missions accountable to different continents will not have the same experience. Once there are multiple bases on the Moon, each experiencing day and night at different times, and communications satellites in orbit above them, things will get more complex still.

“LunaNet is a framework of mutually agreed-upon standards, protocols, and interface requirements allowing future lunar missions to work together, conceptually similar to what we did on Earth for joint use of GPS and Galileo,” said ESA’s Dr Javier Ventura-Traveset in a statement. As Ventura-Traveset notes, we can agree on these systems before they are implemented, or find ourselves stuck afterward, at the mercy of those unwilling to change.

Part of what is needed is a lunar reference time that everyone accepts. That doesn’t mean everyone is on the same time. We use time zones effectively, much as it may horrify flat-Earthers, relying on a system of common references to know what the time is anywhere we need to. It might seem simple to apply this to the Moon, adopting the offsets used to keep the American GPS and the European Galileo global navigation satellite systems in harmony. That means a selenocentric reference frame, providing consistent measurements of distance, as well as time.

However, ESA points out things are not quite so simple. A key component of general relativity is that clocks run at different speeds depending on the gravitational field in which they operate. The lower lunar gravity doesn’t just allow for impressive leaps, it also means lunar clocks will gain an average of 56 millionths of a second a day compared to those on Earth. That might seem trivial, but will soon add up, and could prove catastrophic for joint operations that need to align to the microsecond.

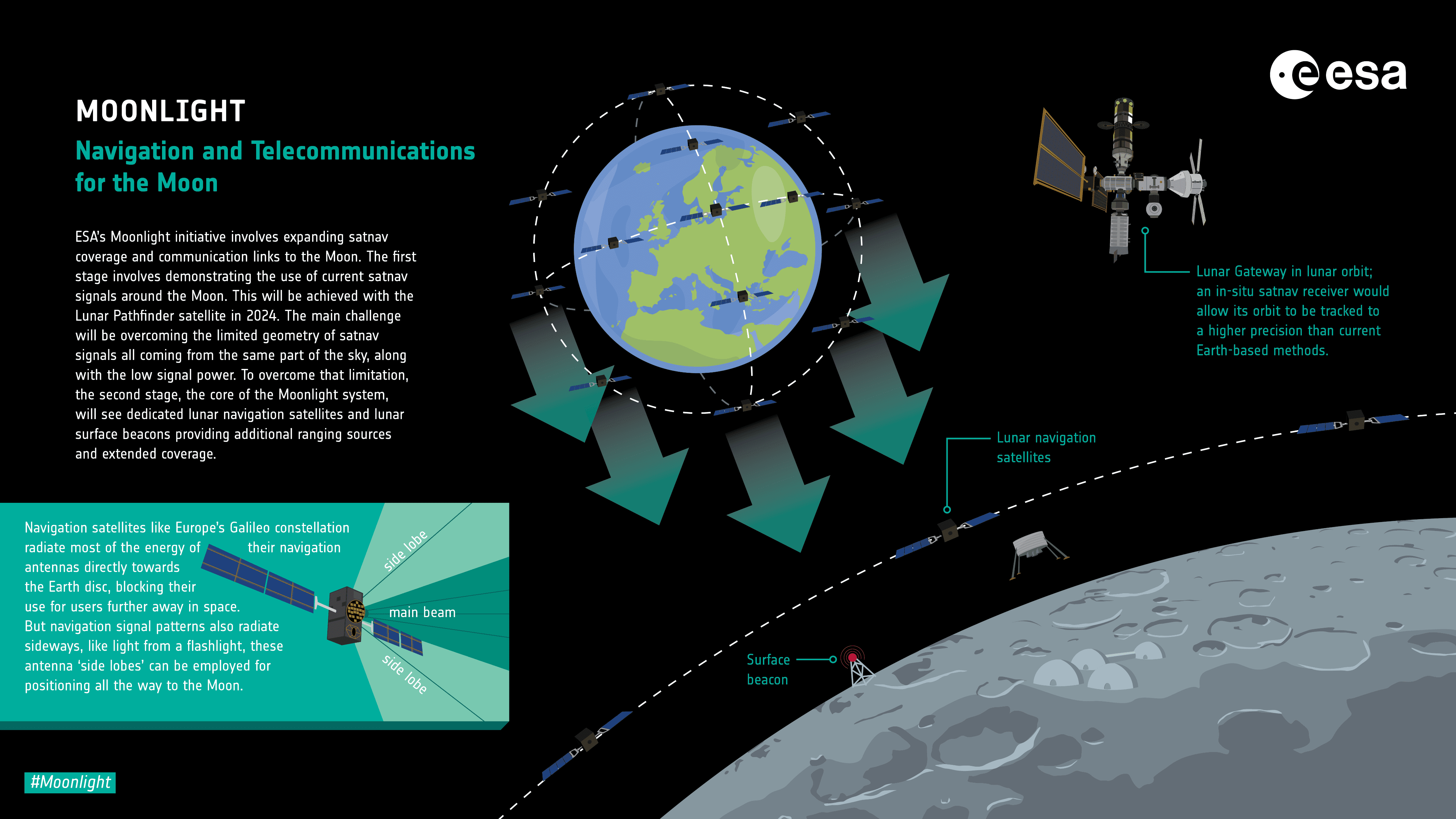

Lunar missions will need to be able to communicate with Earth, as well as find their way. The ESA’s Moonlight program is designed to address both.Image Credit: ESA

Future missions to Mars may operate on local time – a day is close enough to ours that controllers of rovers can function on Martian time with a day/night cycle of 24 hours 39 minutes. It’s unlikely, however, that astronauts will ever be able to go 15 or more days without sleep to make maximum use of the lunar day.

One solution would be a lunar version of the Bureau International de Poids et Mesures, which defines units such as grams and seconds. Not long ago, when cooperation between space-faring nations was better that seemed likely, but alternatives are now being considered to adjust to an era of greater hostility.

Plenty of Earth time will be used up by scientists and engineers from around the world to find an agreed system, but once we have one for the Moon it will create a template for use on other worlds.

“Throughout human history, exploration has actually been a key driver of improved timekeeping and geodetic reference models,” Ventura-Traveset said. “It is certainly an exciting time to do that now for the Moon.”

Source Link: We Need A New Way To Define Time On The Moon