Ever since their discovery in the 19th century, Neanderthals have been unfairly tarnished as the heavy-browed, brutish cousins of Homo sapiens (whose name, by comparison, means “thinking man” in Latin). While the stereotype has been tough to shake, a huge amount of research has helped to reinvent the image of Neanderthals in the 21st century; just like us, they were highly intelligent, culturally complex, and emotionally sensitive beings.

The first Neanderthal remains were discovered in Belgium and Gibraltar in 1829 and 1848, although they were mistaken for being modern humans at the time. It wasn’t until 1856 that German schoolteacher Johann Carl Fuhlrott identified the bones of a strange, extinct human in a cave of the Neander Valley.

Throughout the 19th century, when the theory of evolution was struggling to land in the public imagination, discussions about Neanderthals were ignored or dispelled by most. Those who did acknowledge the species were often most intrigued by its “primitive” nature. In 1864, J. W. Dawson described Neanderthals as “half-crazed, half-idiotic, cruel and strong,” while others felt their skulls had more in common with chimpanzees than humans.

Their inhumane reputation gained traction, culminating in a paper written by paleontologist Marcellin Boule in the early 20th century. Boule had got his hands on the skeleton of a male Neanderthal called “La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1” or “The Old Man”, which he described in detail. Although the prehistoric skeleton was in remarkably good condition, the individual proved to be a deeply unrepresentative member of the species.

“Boule interpreted the elderly, arthritic skeleton as an idiotic hunched-over brute—conflating pathological deformity with species-wide idiocy. This mistake, scholars have argued, resulted in a ‘merciless characterization’ of the species that ‘almost single-handedly’ revolutionized the ways scientists think about Neanderthals,” Paige Madison, a science writer and historian of palaeoanthropology, wrote in a paper published in 2020 by the Journal of the History of Biology.

Madison goes on to argue that the Neanderthal’s reputation of being an “uncouth and repellant creature” actually started in the 19th century, long before Boule’s work. Either way, it’s apparent that stereotypes had solidified by the early 20th century.

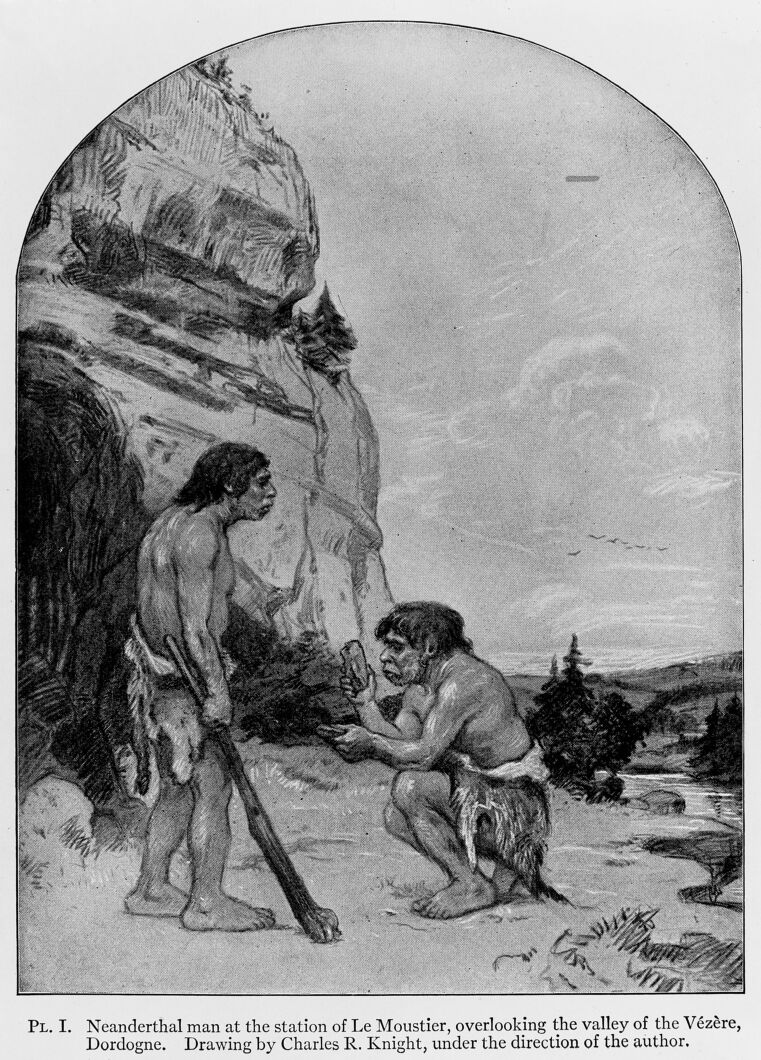

A historic illustration of the so-called “Neanderthal Man”.

When researchers took another look at “The Old Man” of La Chapelle in 1956, they reached entirely different interpretations. His hunched-over back was likely caused by a nasty case of osteoarthritis, not an “ape-like” stature.

Furthermore, he had lost many of his teeth and might have experienced difficulty eating. This could suggest that he had others, perhaps family or his wider community, caring for him in an act of altruism. Later research pushed back against this claim of selflessness, although it’s been suggested elsewhere in the archaeological record many times.

Archaeologists have found several examples of Neanderthals who appear to have lived with disabilities or degenerative diseases that must have required external care by others to reach their age. This ability to empathize with others, and react accordingly using knowledge and skill, shows a high degree of cognitive ability, let alone emotional intelligence.

Along with caring for their loved ones, Neanderthals buried them when they died. In fact, Both Neanderthals and modern humans started burying their dead at approximately the same time – around 120,000 to 100,000 years ago – in roughly the same part of the world.

It can be tricky to interpret burials. Perhaps burials started simply as a way to keep corpses away from scavengers or help to control the diseases and smells associated with decomposing bodies. Alternatively, it might be the sign of a ritual that shows an understanding of death and mortality.

Some archaeologists may have pushed this point too hard. Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan held some of the best-preserved Neanderthal remains ever found. Among the handful of Neanderthal skeletons found at the cave, one appears to have been laid to rest with significant amounts of pollen, which some have argued could be evidence that the individual was laid to rest with flowers in a beautiful funerary ritual.

The Shanidar Cave, an archaeological site located on Bradost Mountain in the Erbil Governorate of Kurdistan Region.

Most scientists don’t buy this explanation anymore, instead believing the pollen was the work of burrowing mammals, bees, and chance.

Nevertheless, plenty of evidence of complex behavior exists elsewhere, such as the cave walls of Europe. We know that Neanderthals were artistic, a trait we associate with advanced cognitive abilities because it demonstrates abstract thinking, symbolic communication, and creativity.

Some of the earliest examples of “art” were created by the hands of Neanderthals. One especially remarkable example can be found in Spain’s Cueva de Ardales where, some 65,000 years old, Neanderthals painted the stalagmites of the cave using ochre, a red-tinged earth pigment that’s rich in iron.

Elsewhere, there are several examples of Neanderthals placing their palm on the cave wall, then flicking and spraying red ochre, leaving behind a perfect hand shape.

In the book Human Evolution and Survival, Nasser Malit, an associate professor of biological anthropology at the State University of New York, writes a chapter titled “Are the Neandertals Finally Becoming Human?” that looks at how perceptions of Neanderthals have evolved since the 19th century.

Neanderthals have always been human, technically, in the sense they belong to the genus of great apes known as Homo alongside our species. However, Malit is asking whether Neanderthals are perceived as sharing some sense of “humanity”, particularly in their capacity for compassion, creativity, and consciousness.

The answer to that question has to be yes: we can now say with confidence that Neanderthals were just as “human” as Homo sapiens.

You could even make a case that they were more “human” than us. Among the many factors that led to their extinction, some argue that Neanderthals were effectively outcompeted by Homo sapiens (or, alternatively, many believe they were outbred and absorbed into our species). It might be argued that Homo sapiens had the upper hand because of their violent and expansionist tendencies, not their sensitivity and compassion.

If that’s the case, does that make Neanderthals the “nice guys” and us the “baddies”?

Source Link: Were Neanderthals Even More "Human" Than Us?