Three years after evidence emerged that the quasi-moon known as Kamo’oalewa is formed from a chunk of Earth’s one true Moon, we may know just where it comes from. Besides showing the rapid progress in knowledge about the exceptionally recent field of quasi-moons, the discovery honors a scientist who believed in the plurality of worlds.

Until recently, the inner Solar System was thought to be a pretty lonely place, with just three moons between four planets, plus a few asteroids with orbits closer than the main belt. However, a by-product of the search for objects that could pose a threat to Earth is the discovery of so-called quasi-moons. These objects orbit the Sun on the same timeline as the planet, causing them to stay close for years, before shifting to horseshoe-shaped orbits.

The first of these, a quasi-moon of Venus, achieved some fame thanks to the delightful way in which it got named Zoozve.

In the process, we have learned that Earth has a few quasi-moons of its own. They’re all small – some the size of elephants. The largest we’ve found is Kamo’oalewa, which is about the length of two blue whales (oh you want a less zoological measurement? – try about 60 meters, 200 feet, tops). A quasi-satellite doesn’t exactly translate as a second Moon, but on the asteroid-to-moon spectrum, Kamo’oalewa is more towards the moon end, and maybe deserves the title.

Five years after its discovery, Kamo’oalewa’s spectrum was analyzed and found to look a lot like that of some lunar rocks, but nothing like any known asteroid.

The idea that Kamo’oalewa might have been knocked off the Moon in an asteroid strike gained credibility from the fact that its orbit is more stable than the other quasi-moons, and has a much lower velocity compared to the Earth-Moon system, as would be expected of something with nearby origins. Modeling last year of the required conditions to make an object like this showed the idea to be plausible.

Still, there are a lot of impact craters on the Moon. Identifying the one that gave birth to Kamo’oalewa seems like a fool’s errand, but that is what a new paper claims to have done.

Although Kamo’oalewa is fairly small, the crater from which it came would have to be much larger – at least 10-20 kilometers (6-12 miles) across, the authors calculate. Moreover, it’s likely to be relatively young. Kamo’oalewa’s orbit may be stable by the standards of quasi-satellites, but it’s unlikely to survive for hundreds of millions of years given the tug of planets’ gravity and the possibility of a collision with some other object.

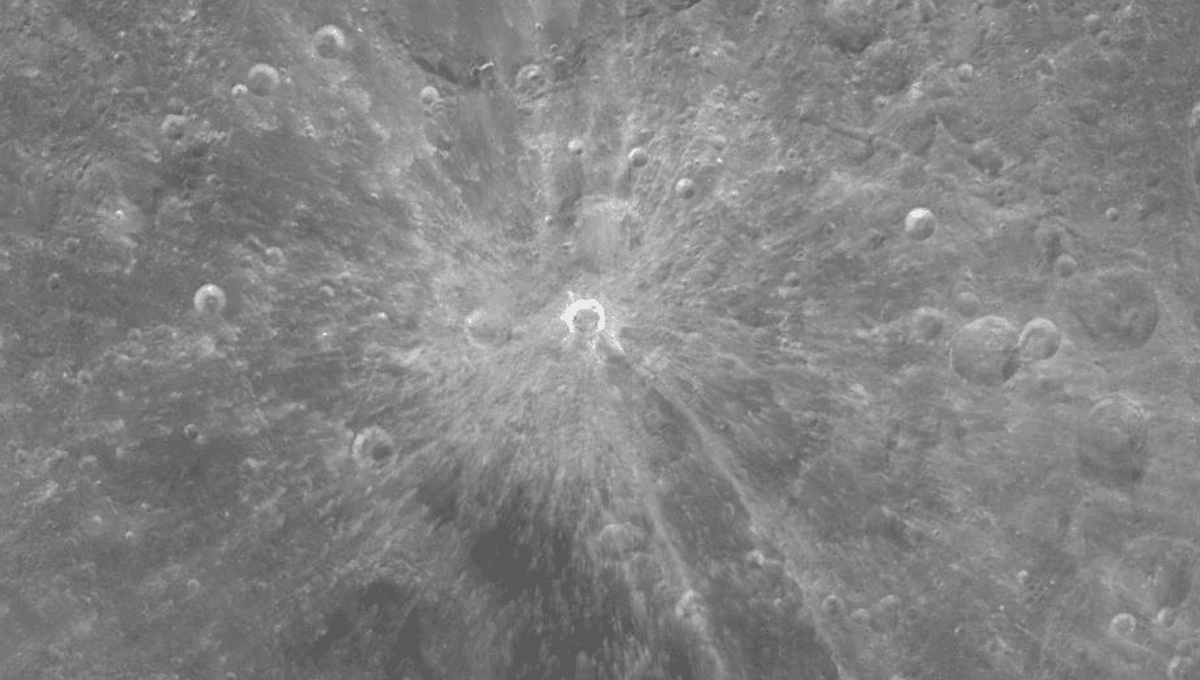

That makes for a short list of possibilities, and the authors think the crater Giordano Bruno is the most likely candidate. It’s 22 kilometers (14 miles) wide, and thought to be between 1 and 10 million years old,

The spectrum collected from Kamo’oalewa most closely matches the samples brought back by the Apollo 14 mission, as well as those collected by the Soviet Luna 24 lander, and some meteorites knocked off the Moon.

We’re going to need a more detailed analysis of Kamo’oalewa, probably by landing there, to be sure of the match. Giordano Bruno has attracted the authors’ suspicions because it is thought to be the youngest lunar crater of suitable size, but there are others, such as the much more famous Tycho crater, that might be young enough.

If the authors are right, quite a few other objects of similar size would have been ejected when a 1.6-kilometer (1-mile) wide object hit the Moon and created the Giordano Bruno crater. Most would since have hit the Earth, or been ejected from the Solar System, but there could be other survivors to look out for.

“Asteroids tens of metres in size have never been explored by space missions and thus are among the least understood small bodies, even though they represent the most frequent [near-Earth asteroid] hazard and could be the most accessible space resources,” the authors note. The planned Tianwen-2 mission to Kamo’oalewa next year could change all that, and provide us with a comparison of how material evolves on and off the Moon.

Not having any samples of Giordano Bruno, we can’t measure its age precisely. However, its steep walls and prominent surrounding rays speak to a recent birth, as does how few smaller craters have appeared on top. The crater achieved some fame when its creation was proposed to be the cause of the events described by medieval monks, but the idea it’s as young as that is now largely discredited. The crater is named after the philosopher burned for heresy after proposing the stars had planets of their own, although the execution probably had other motivations.

The study is published in Nature Astronomy.

Source Link: We’ve Found Where On Our First Moon Our Second Moon Came From