What happens in the Pacific doesn’t stay in the Pacific. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle describes how a pattern of climate fluctuations in the Pacific Ocean has a global impact on the world – from wind, temperature, and rainfall patterns to the intensity of hurricane seasons and even the distribution of fish in the seas.

It’s hard to understate the importance of the ENSO on our world – and in 2023 it’s all the more significant, as El Niño is forecasted to return.

We’ve been in the midst of continuing La Niña events since September 2020. However, that’s due to change in 2023 with a flip over to El Niño, which many are predicting could deliver a string of unprecedented heat waves. The impact could be so significant that we might see some of the hottest weather since records began and, as a result, potentially tip the average global temperatures over 1.5°C(2.7°F) before pre-industrial levels, which is a key milestone of the climate crisis.

Here’s how it all works, according to the NOAA.

Typically in the Pacific Ocean, winds blow west along the equator, delivering warm water from South America toward Asia. To “replace” that warm water, cold water rises from the depths of the Pacific to the surface. In episodes of El Niño and La Niña, however, this state of events is disturbed.

What is El Niño?

El Niño is sometimes referred to as the “warm phase” of the ENSO. During El Niño, winds along the equator are weaker. Warm water is pushed back east toward the west coast of the Americas. As a result, less cold water rises toward the surface.

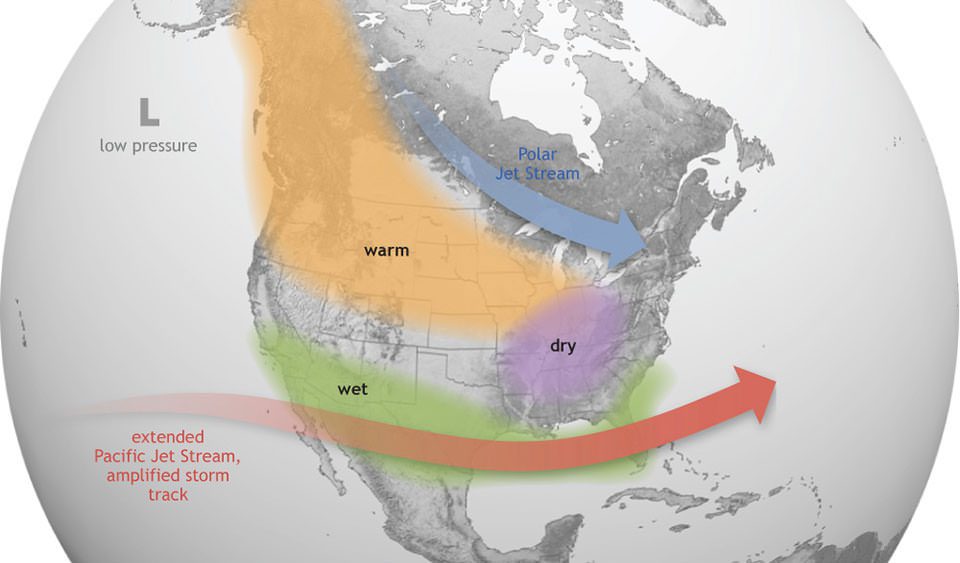

The impact of this temperature change is profound. The warmer waters cause the Pacific jet stream to move south and extend, causing drier and warmer weather to hit northern parts of the US and Canada, but wetter weather in southern states.

Over in the Atlantic Ocean, El Niño actually weakens hurricane seasons while strengthening hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basins.

In Africa, El Niño fuels increased rainfall in East Africa, while causing decreased rainfall in southern Africa, West Africa, and parts of the Sahara region.

The warmer water also has an impact on marine life. During El Niño, less nutrient-rich water is brought up from the depths of the Pacific, resulting in fewer phytoplankton to support the wider ecosystem. As a result, fish are known to die or migrate elsewhere.

An El Niño is declared when sea temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific rise 0.5°C (0.9°F) above the average.

El Niño means “the boy” in Spanish. It’s thought to have originated as “El Niño de Navidad” centuries ago when Peruvian fishermen named the weather phenomenon after the newborn Christ. Notably, El Niño can often peak around December time.

A map showing how El Niño influences weather in North America. Image credit: NOAA

What is La Niña?

It’s easy to imagine El Niño and La Niña as two sides of the same coin, like yin and yang. As opposed to El Niño, it’s often called the “cold phase” of the ENSO.

During La Niña, which means “the girl”, westward winds in the Pacific around the equator are even stronger than usual, driving more warm water toward Asia. Accounting for the drop in temperatures at the surface, colder nutrient-rich water rises from the ocean depths along America’s west coast.

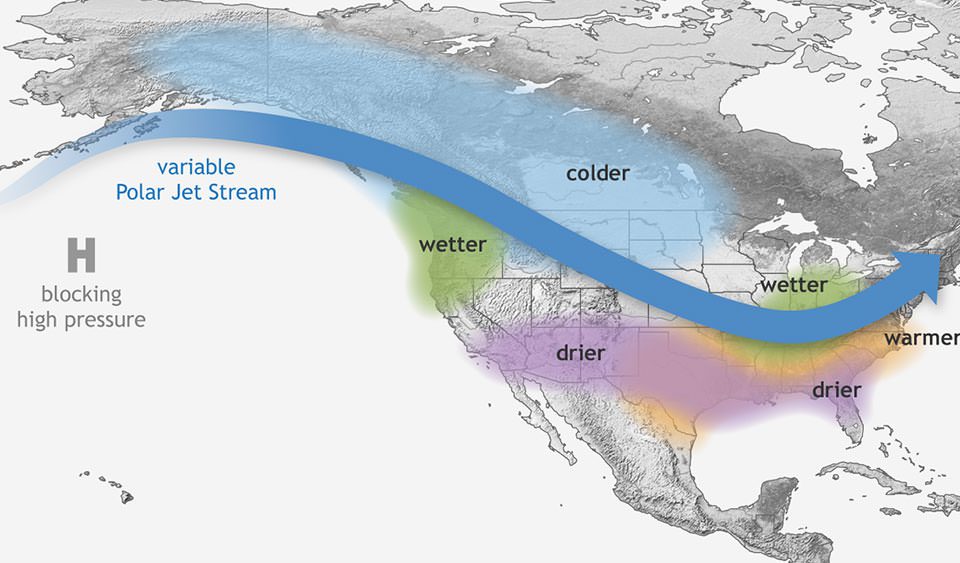

The cold waters in the Pacific push the jet stream northward, resulting in drier weather in the southern US, but notably wetter and colder weather in the Pacific Northwest and Canada. We also see warmer winter temperatures in the South during la Niña and cooler temperatures than normal in the North.

La Niña can additionally lead to less severe hurricane seasons in the Pacific, but fuels a more severe hurricane season over the Atlantic. We can also expect to see drier conditions in East Africa, as well as wetter weather in Australia and parts of Southeast Asia.

Map showing how La Niña impacts weather in North America. Image credit: NOAA

How long do El Niño and La Niña typically last?

El Niño and La Niña events arise every two to seven years on average and typically last nine to 12 months, although they can persist for much longer, as we’ve seen in recent years.

They both tend to develop during the spring (March to June) and reach their peak intensity in the late autumn or winter (November to February), before dying down during the spring or early summer (March to June).

El Niño and Climate Change

Given its complexity, it’s still not certain how the ENSO is being influenced by climate change. Scientists have only been scientifically studying the frequency of El Niño and La Niña events in recent decades, so there’s still not a lot of data to go by.

That said, there is some evidence that warming temperatures are favoring the emergences of La Niña since higher temperatures above the Pacific fuels the westerly trade winds towards Asia, fuelling this side of the cycle.

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

Source Link: What Are El Niño and La Niña? The Giant Forces That Shape Our World