The discovery of the embryo of a choristodere, a type of crocodile-like reptile, has overturned what biologists thought about the development of egg laying. The discovery has big implications for how mammals and birds, as well as reptiles, developed their approach to having young.

The fossil has traces of egg around it, but this was nothing like a modern bird’s egg. Instead, it was a “parchment egg”, and represents the first example of an alternative approach to bearing young among archelosaurs, the branch of animals that includes crocodiles and dinosaurs, including modern birds.

Although many dinosaur eggs have been found, we don’t have examples from early dinosaurs, which led to some guesswork. It was believed the first dinosaurs, and the reptiles that preceded them, laid hard-shelled eggs, like those that have fossilized, and are used by birds, the surviving dinosaurs. Indeed, according to this story the development of hard-shelled eggs was key to reptilian success. However, the description of this embryo in a new paper throws that into question.

As the University of Bristol’s Professor Michael Benton told NPR, the old question of “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” has long been settled. The chicken evolved from other egg-laying birds, so eggs easily precede chickens. However, Benton has put more nuance to the matter. For one thing, not all eggs are the same.

Like fish, amphibians’ eggs need to be laid in water, which prevented frogs from ruling the land. It had been thought that hard-shelled eggs freed reptiles of this bond to waterways, creating what some have called a “private pond” they could deposit wherever it suited them.

The break from laying eggs in water is considered so profound that mammals, reptiles, birds, and extinct relatives are collectively known as amniotes, after the amnion, the membrane which protects the embryos of all these animals.

However, as humans and other mammals (monotremes excepted) know well, there is another way to get free of water: give birth to live young. Where reptiles’ amnion forms a sack within the egg, in humans it surrounds the embryo and amniotic fluid within the womb. There’s also an intermediary option, known as “Extended embryo retention” (EER).

“EER is common and variable in lizards and snakes today,” said Dr Joseph Keating of Nanjing University in a statement. “Their young can be released, either inside an egg or as little wrigglers, at different developmental stages, and there appears to be ecological advantages of EER, perhaps allowing the mothers to release their young when temperatures are warm enough and food supplies are rich.”

“Sometimes, closely related species show both behaviors, and it turns out that live-bearing lizards can flip back to laying eggs much more easily than had been assumed,” said Nanjing University’s Professor Baoyu Jiang.

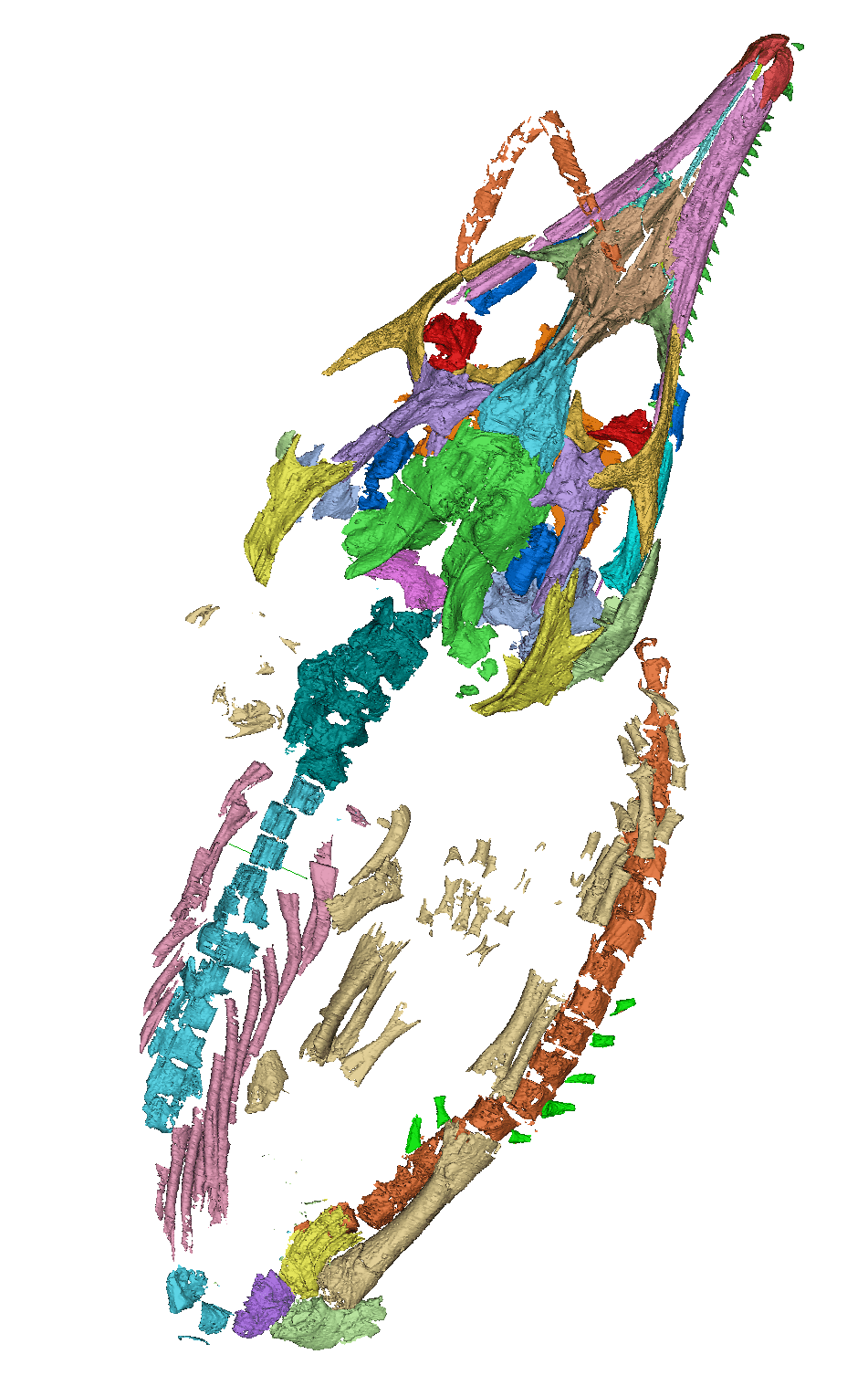

Skeleton of a baby choristodere, suspected to be an Ikechosaurus, from the Early Cretaceous of China, found curled up inside traces of a parchment-shelled egg.

Image credit: Baoyu Jiang, Nanjing University

When species that practice EER do lay eggs, these are called “parchment eggs” because they are so thin and vulnerable. It’s not a good approach if eggs need to survive for a long time before hatching, but it consumes less resources than go into making hard shells.

If EER existed in dinosaurs, and is common in squamates (lizards and snakes) and near universal in mammals, it is present in all major arms of the amniote family, the paper notes. This makes it likely it preceded the development of (hard) egg laying.

Perhaps because we see live birth as a mammalian advance on our reptile ancestors, it had been assumed that such flexible approaches were a recent development, and the first amniote encased its amnion in an egg.

Yet the giant sea monsters of the dinosaur age, such as ichthyosaurs, birthed live young.

The authors argue EER existed at the base of the amniote family tree, with hard-shell eggs and consistent live births both much later developments.

Amnions probably developed, they claim, as a way to control fetal-maternal interactions within the body. Only later did some animals build on this by creating a hard egg around the amnion and letting it develop for long periods outside the body.

The story of the revolutionary hard shell is “wrong” Benton told NPR. “It wasn’t the private pond, it was the extended embryo retention and live birth. That seems to be the primitive state for reptiles.”

“Whether the first amniote babies were born in parchment eggs or as live, snapping little insect-eaters is unknown, but this adaptive parental protection gave them the advantage over spawning earlier tetrapods,” Benton said in a statement.

The study is published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Source Link: What Came First: The Chicken, The Egg, Or Reptile Live Birth?