In 1994, the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, pointed the Hubble Space Telescope at a dark and seemingly empty patch of sky for 100 hours.

When Hubble was launched in 1990, like with the JWST, its capabilities weren’t immediately clear. Ahead of being turned on, astronomers attempted to analyze what objects it would be able to see, based on what we know of ground telescopes. One paper from influential astronomer John Bahcall argued that the telescope would not be able to see distant galaxies that we had not already seen from telescopes on Earth.

But in May and June of 1994, Robert Williams, an astronomer who went on to be President of the International Astronomical Union, looked at wide field photos taken with the camera at a wide range of wavelengths, and believed it showed more distant objects could be captured by Hubble. Williams was in charge of 10 percent of Hubble’s operational time, as director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, and decided to test its capabilities further, pointing the telescope at a patch of sky for a long exposure time to see if it revealed more distant objects, further into the past.

“We didn’t know what was there, and that was the whole purpose of the observation, basically – to get a core sample of the universe,” Williams said at the time. “You do the same thing if you’re trying to understand the geology of the Earth: Pick some typical spot to drill down to try to understand exactly what the various layers of the Earth are and what they mean in terms of its geologic history.”

The team needed to look at a patch of dark sky with no other nearby objects that could ruin the exposure, ruling out everything on the plane of our own galaxy. So too were any stars that the Earth or Moon would pass in front of during the exposure. Eventually, they settled on an area roughly the size of a pin head held an arm’s length away, near the Big Dipper in the constellation Ursa Major.

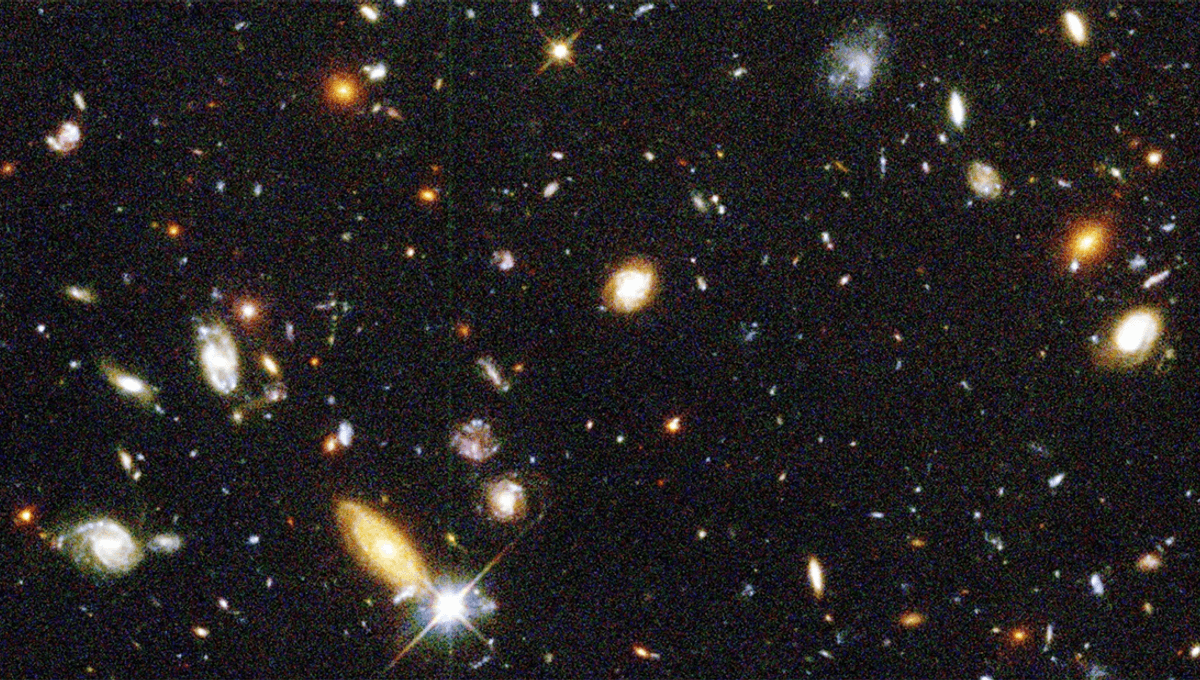

The point of sky, which looked relatively empty from ground telescopes, proved to be anything but. When Williams pointed the telescope at it for 100 hours, the result was the Hubble Deep Field, the deepest view of the universe up to that point, and the furthest back into the past that humanity had ever seen. It was, of course, filled with galaxies, including ones that could not be seen by ground-based telescopes, and information about the state of the universe billions of years in the past.

Source Link: What Happened When The Hubble Telescope Stared At "Nothing" For 100 Hours