As a wise and leonine monarch once said, “Everything you see exists together in a delicate balance. As king, you need to understand that balance […] we are all connected in the great Circle of Life.”

But what if that circle was more of an… oval? What if, instead of each species being just as important as every other one, they almost all kind of depended on just one or two? Well, then you’d have a keystone species.

What is a keystone species?

Humans like to think of themselves as the masters of manipulating our surroundings – and it’s true that very few animals out there are quite as ambitious when it comes to affecting the world. We’ve built cities where there was once wilderness; we can divert rivers and raise planetary sea levels; and we kill off entire species for little more than the hell of it.

So sure, maybe we’re the best at it (termites don’t @ us). But we’re by no means alone.

“It’s almost Orwellian: Some species are more equal than others,” Larry Crowder, a biologist at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, told National Geographic. “In terms of the structure of ecosystems, yeah, some species are more important than others.”

The concept of a “keystone species” goes back to the 1960s, when the then-fledgling ecologist Robert Paine decided to chuck a bunch of starfish into the Pacific Ocean.

No, really. “Paine realized that if he wanted to understand how nature worked – the rules that regulated animal populations – he would have to find situations where he could intervene and break them,” explained developmental biologist and author Sean B Carroll, a professor of molecular biology and genetics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Vice President for Science Education at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, in his 2016 book The Serengeti Rules: The Quest to Discover How Life Works And Why It Matters.

“In the specific case of the roles of predators, he needed a setting where he could remove predators and see what happened – what would later be described as ‘kick it and see’ ecology,” he wrote. “Hence, the starfish-hurling.”

Over the course of the next year, with Paine regularly flinging starfish away from the rocks along one area of the coast, the knock-on effects were stark. Without the pentapedal predators to pick them off, the local barnacle and snail populations exploded; four species of algae, on the other hand, had mostly disappeared, while local limpet and chiton species had gone completely.

Compared to an adjacent outcrop, which Paine had left in its natural starfished state, the biodiversity around the rocks had been cut by half. And the casualties weren’t even limited to species below the starfish in the food chain: local populations of anemones and sponges had also decreased, despite having no obvious ecological connection to the flung-away starfish.

It was this, along with similar experiments in New Zealand and Alaska, that solidified Paine’s concept of what he named “keystone species” – species that exert extremely high influence on their surroundings relative to their population. Remove a keystone species, and the whole ecosystem is thrown off-balance; at best, it will be forced to adapt rapidly to new or invasive species taking over the habitat, and at worst – well, at worst, the ecosystem can cease to exist entirely.

Which species are keystones?

Given how important they are, you might be surprised at which species actually qualify for keystone status. “The public perception of a keystone species is that they are the large terrestrial mammals,” Diane Srivastava, a community ecologist at the University of British Columbia, told Quanta Magazine earlier this year.

“But actually, most of them are not,” she explained. “Most keystone species are aquatic. Many of them are not predators. There’s a good number of invertebrates.”

So how do we identify which species count? It’s not as simple a question as it may sound – and since the 1990s, in fact, some ecologists have started to worry that the term is so fuzzy as to be borderline meaningless. To give you an idea of how wide the range of potential keystone species is: one analysis from last year surveyed more than 150 studies from the past 50 years or so, and concluded that at least 230 different species have been labeled as keystones at some point.

“The problem is that there are no standards to which researchers are held in designating their study organism as a keystone,” Bruce Menge, a community ecologist at Oregon State University who studied under Paine as a grad student, told Quanta. “Anyone is free to suggest, argue or speculate that their species is a keystone.”

Still, some species stand out as obvious examples. Beavers, for instance, have been described as “nothing less than continent-scale forces of nature and in part responsible for sculpting the land upon which Americans built their communities” – not bad for a once near-extinct rodent.

And why? Because of their dams: by constructing these signature pieces of infrastructure, the animals can literally reshape a landscape into thriving wetland ecosystems, creating habitats for waterfowl and encouraging populations of frogs, fish, and invertebrates.

“Beaver wetlands are pretty unique,” Nigel Willby, professor of freshwater science at the University of Stirling, told the BBC in 2023. “Anyone can make a pond, but beavers make amazingly good ponds for biodiversity, partly because they are shallow, littered with dead wood and generally messed about with by beavers feeding on plants, digging canals, repairing dams, building lodges etc.”

“Basically, beavers excel at creating complex wetland habitats that we’d never match.”

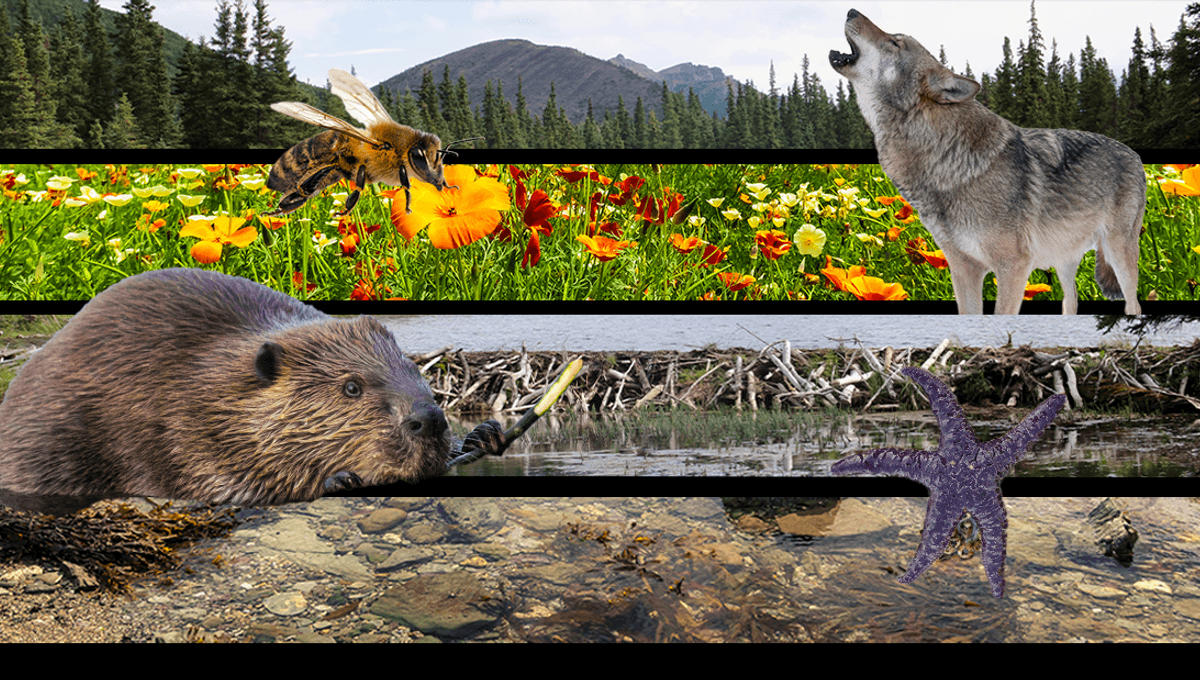

Other keystone species are less glamorous. Using an analytic technique designed to sort items into related clusters, UC Davis ecology doctoral student Ishana Shukla and her colleagues were able to isolate five separate types of keystones: some, like the beaver, are small mammal terraforming specialists; some, like sharks or wolves, are important thanks to their role as large predators, imposing what is genuinely known in scientific circles as a “landscape of fear” on their ecosystems.

But the other three types of keystone species – middle-of-the-food-chain species like the European sprat or bullhead; ecological niche-fillers like honeybees; and what the researchers referred to as “smaller, lower-level invertebrate consumers”, such as sea urchins or cabbage butterflies – are less likely to grab the headlines. And that’s a problem.

“We’ve identified a whole swath of keystones that aren’t necessarily getting conservation action or conservation attention,” Shukla told Quanta. “But we can see that they are massively important to our ecosystem.”

What happens if a keystone species goes extinct?

By definition, a keystone species has an outsized effect on its ecosystem. So, what happens if one disappears?

We don’t actually need to use too much imagination for this one – we have a ready-made example to hand. Once the most widely distributed mammal in the world, centuries of human interference have driven the grey wolf to near or full extinction in many of its original habitats.

The disappearance of this keystone species had effects that we’re only now beginning to fully understand – and it’s actually thanks to their recovery and reintroduction in places like Yellowstone that we’re seeing how vital they are to the ecosystem.

For example, “one way in which wolves wield influence is by preying on coyotes, which produces ripple effects across the system,” wrote Christopher J. Preston, a Professor of Philosophy from the University of Montana who specializes in environmental ethics, in a 2023 article for The Conversation. “Fewer coyotes means more rodents, which in turn means better hunting success for birds of prey.”

Similarly, “elk avoid some areas when wolves are around, resulting in ecological changes that cascade down from the top,” he explained. “Vegetation can recover, which in turn may benefit other species.”

These strong, top-down effects are known as “trophic cascades” – and they can be much more complex than you might realize. Indeed, the presence of wolves in an area can induce the kinds of changes human geoengineers can only dream about: according to one 2016 study, reintroducing the canids across all North American boreal forests could decrease the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere by up to 99 million tonnes per year. That’s the equivalent, the researchers noted, of taking up to 71 million cars off the road entirely.

And here’s the thing: that’s the result of just one keystone species – one which we, thankfully, were able to bring back from the brink. But how many other ecosystems have been lost forever thanks to human overreach? How many are currently disappearing?

“Trophic cascades have been discovered across the globe, where keystone predators such as wolves, lions, sharks, coyotes, starfish, and spiders shape communities,” Carroll wrote. “And because of their newly appreciated regulatory roles, the loss of large predators over the past century has Estes, Paine, and many other biologists deeply concerned.”

“Today, of course, one predator has more influence than any other,” he warned. “We have created the extraordinary ecological situation where we are the top predator and the top consumer in all habitats. ‘Humans are certainly the overdominant keystones and will be the ultimate losers if the rules are not understood and global ecosystems continue to deteriorate,’ Paine says. The only species that can regulate us is us.”

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

Source Link: What Is A Keystone Species, And Why Are They So Important?