Despite their popularity within certain fantasy games or among some new age Pagan movements today, there is much we do not know about the Druids, an ancient social class often associated with mysticism and magic. That is because we have little contemporary evidence relating to them, which has enabled subsequent generations to imagine and add new details to these enigmatic people.

So what do we know ?

The druids were a priestly social class among the ancient Celtic peoples who lived in Ireland, Britain, and Gaul (a region encompassing modern France and much of Western Europe).

Although druidism is likely extremely old, we do not know when it began and even the origins of the word “druid” is unclear. Its first use appears in Latin and Greek texts, despite it having Celtic roots. There is a popular belief derived from early etymologies that it comes from doire, an Irish-Celtic word for oak tree, which was associated with knowledge and wisdom. However, later etymologies tend to see it as meaning “strong seeing” or “strong see-er”.

Most of the information we have about the druids comes from outside commentators, especially the Romans. This is the first issue we have when examining their history – there is little way of knowing the truth of such accounts.

What did other people say about these ancient priests?

According to Julius Caesar, who invaded Gaul in the 50s BCE, the druids were “engaged in things sacred, conduct the public and the private sacrifices, and interpret all matters of religion.” They were held in the highest regard among the Celts, who turned to them for instruction in all things juridical and spiritual, both public and private. They were not required to perform manual labor or to serve in the military, and they were free from paying taxes. Their main role was, Caesar suggests, to serve as intermediaries between the spiritual world and everyday life, but they were also responsible for human sacrifice.

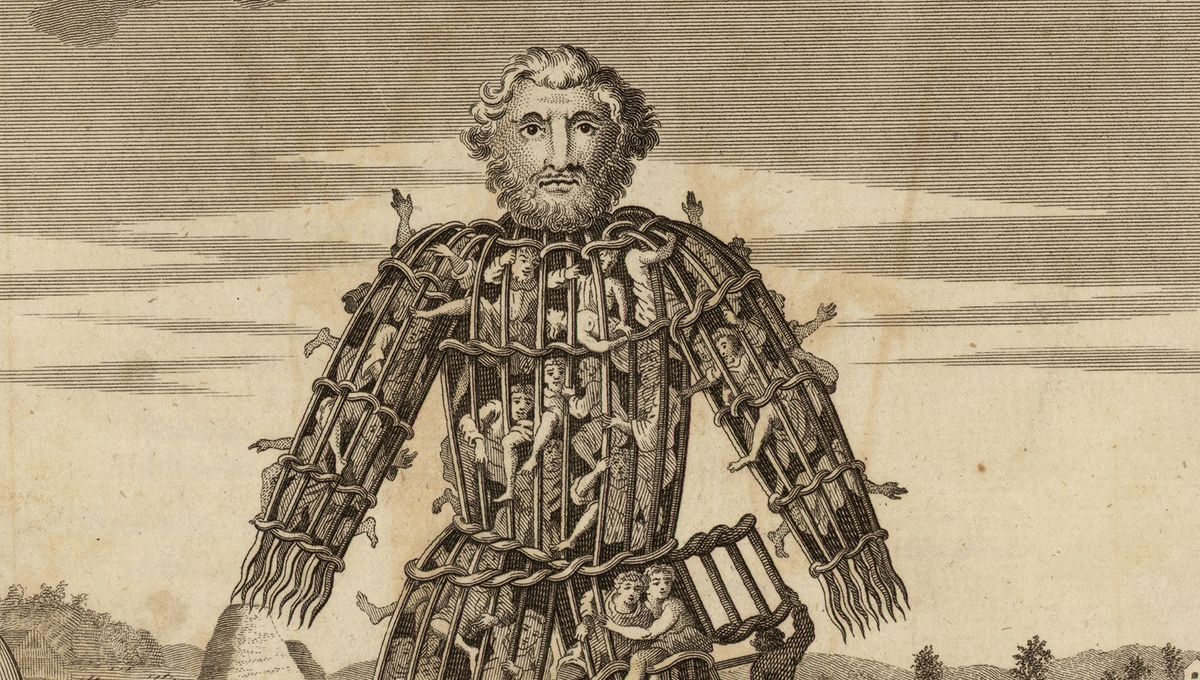

This aspect of Druid practice, Caesar suggests, was a crucial part of their role within the community. He described how those deemed worthy of ceremonial killing were placed into large wicker effigies – a wicker man – where they would be burnt as offerings. Caesar’s descriptions of Druids has remained one of the most important accounts related to these priests, but it is largely drawn from hearsay and is considered to be anachronistic as it relies on the work of earlier authors, such as Posidonius.

Other commentators such as the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus also referred to the Druid’s use of sacrifice, but as a way to divine the future, rather than to appease the gods. The druids, he wrote “prepare a human victim, plunging a dagger into his chest; by observing the way his limbs convulse as he falls and the gushing of his blood, they are able to read the future.”

The murky truth about human sacrifice

Despite the gory and imagination-stirring details of these accounts, there is significant doubt among historians as to the extent to which human sacrifice was actually practiced among the Celts.

Firstly, although sacrifice was certainly a feature of their religious practices, the victims were most often animals, rather than people. Secondly, the idea that these mysterious priests practiced such a savage act could have also served as useful propaganda for the conquering Romans, who feared their political influence over the Celtic communities. There is indeed some archaeological evidence that Iron Age Celts may have practiced ritual killings, but it was probably less common than is often thought if it did occur, though even this is far from conclusive.

Caesar believed that Britain was the center of druidism and that people from across Gaul would travel there to become druids, but yet again this is not a certainty.

Today, people often associate Stonehenge with the Druids – however, it is unclear whether the Druids had anything to do with the construction of this ancient monument, as it predates the first mention of them in the historical record by about 2,000 years. Moreover, there are no links within contemporary written texts connecting Druids to stone circles or similar monuments, and certainly not Stonehenge. Instead, their devotional rites were said to take place in wooded groves.

What did the Druids believe?

Like the Romans, the Druids were polytheistic, worshipping a pantheon of gods and lesser divine entities. However, 19th-century revivalists and modern Pagan/neo-Druids have merged druidism with more Christian ideas, recharacterizing them as monotheists believing in a single creative force above all others. Such claims are built on romanticized ideas that are largely divorced from historical reality. The evidence such proponents cite was produced in the 18th and 19th centuries, rather than during the classical period. It is also these sources that have linked Druidism to Stonehenge.

What happened to the Druids?

As Christianity spread across Europe, the Druids were pushed further into obscurity. By the 8th century CE, their numbers seem to have dwindled to a small presence in Ireland. Over centuries, the image of the Druid shifted from a priestly figure to a kind of magician or healer in Medieval folklore and literature.

Despite modern revivals and imitations of their imagined practices, the historical reality behind the Druids remains unknown and impossible to verify. We do not really know who they were and whether it is even possible to talk of “Druids” as a collective group rather than a blanket term covering anything from priests to bards to philosophers and teachers. The archaeological record is equally contentious, as we still do not have any artifacts that are unambiguously linked to their mysterious ways.

For some, these gaps are fertile grounds for interpretation and adaptation, but to others, they remain tantalizing reminders of how little we really know.

Source Link: What Is The History Of Druids And Who Were They Really?