In 1812, Friedrich Mohs created a scale to measure the hardness of substances. There were problems with the scale, which have inspired other scientists to invent alternatives. Nevertheless, these have issues of their own, and the Mohs scale continues to be the most widely used. It is, however, sometimes misinterpreted, so time to explain what it does, and doesn’t, say.

Origins of the Mohs scale

People have been comparing the hardness of substances by seeing whether they will leave a mark since ancient times. The oldest recorded example was by Theophrastus in around 300 BCE, in his treatise On Stones. However, Mohs put the idea on a more mathematical, post-Enlightenment, footing.

Mohs’ scale was apparently simple. He defined a substance’s hardness by its ability to scratch others, and not be scratched by them. Therefore, the hardest substance, which he allocated a value of 10, was the one that could scratch anything else, without in turn being scratched. Not surprisingly, this value was awarded to diamonds. It turns out not all diamonds are equally hard, so a Mohs value of 10 is now given to Type IIa diamonds, the hardest type of the gem.

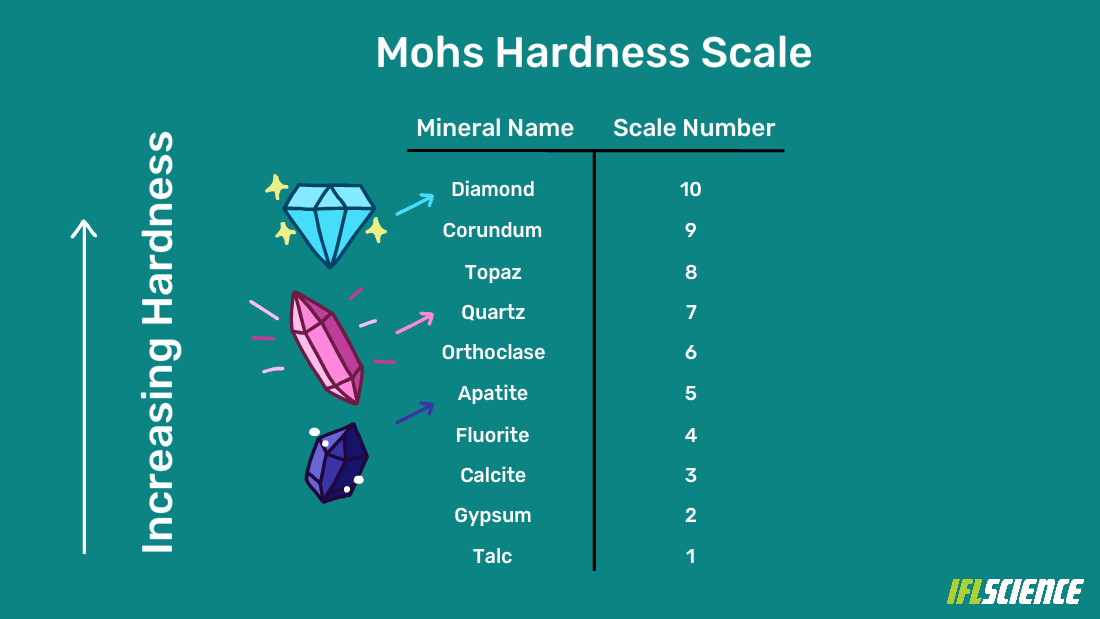

From there, Mohs picked nine other familiar solids, assigning each of them a natural number. In order from one these were: talc, gypsum, calcite, fluorite, apatite, orthoclase feldspar, quartz, topaz, and corundum.

The Mohs hardness scale.

Since then, other substances have been added using decimals. This guide, for example, slots in such relevant items as nails, both steel and finger.

What it lacks

The downside of Mohs’ scale is that by placing each of his starting items equally far apart, Mohs hid the real differences. For example, although gypsum, calcite, and fluorite are in the right order, the gap between calcite and fluorite is a fair bit smaller than between gypsum and calcite, whether measured linearly or logarithmically. Yet on the Mohs scale, the separations are equal. Amber might have been a better choice than gypsum for a somewhat evenly spaced scale.

There’s also an enormous gap in the true hardness of diamond and corundum; diamond is almost four times as hard on measures of absolute hardness. Mohs’ wasn’t to blame for these faults – he lacked the technology to measure hardness more precisely, and was not familiar with many of the substances closer to diamond on the scale.

There are also substances that probably exceed diamonds on the hardness scale, and should be assigned numbers greater than 10, although it turns out establishing this is not exactly easy.

Why we use it

Nevertheless, Mohs’ scale is still used, unlike many products of 19th-century science, which are largely now seen as historical curiosities that served as stepping stones to better modern versions.

The reason is that it’s highly practical to use the Mohs scale in the field, where more precise equipment is unavailable. If you find a mineral you don’t recognize it’s unlikely you will have a diamond anvil at hand to measure its absolute resistance to pressure. It’s easy, however, to carry a sample of Mohs’ original items, or cheaper counterparts, and test which ones will scratch the stone in question.

Such an easy measure of approximate Mohs hardness can help identify your find. If your discovery turns out to contain valuable minerals, which can only be accessed by griding it down, knowing the Mohs number tells processors what it will take to grind it down – which can also give a fair idea of the cost.

These turn out to be more widely relevant concerns than how much force must be applied to a diamond indenter to deform a substance, the measure used by the Vickers scale.

Misuse

The Mohs scale is often misused by people seeking to “prove” that ancient civilizations lacked the tools to create their surviving monuments. Once that conclusion is reached, those making these claims announce the true builders must either be aliens using laser cutters, or some superior lost civilization, who curiously always seem to be represented as white.

A particularly popular version is that the Egyptians only had copper tools, yet left a legacy in limestone and granite, which are much further up the scale. Since a material lower on the scale can’t scratch, let alone engrave, one with a higher number, the argument goes, it must have been aliens.

However, as a number of videos have demonstrated, Egyptian tools can be used to replicate all sorts of incisions in stones with much harder Mohs values.

Source Link: What Is The Mohs Hardness Scale?