As Johnny Cash once sang: “Love is a burning thing, and it makes a fiery ring […] And it burns, burns, burns, the ring of fire; the ring of fire.” This isn’t wrong, apart from one little detail: the first word should have been not “love”, but “a 40,000-kilometer-long horseshoe-shaped tectonic belt running around the edges of the Pacific Ocean and providing 75 percent of all the world’s volcanic activity and 90 percent of its earthquakes.”

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

Now that is a Ring of Fire.

What is the Pacific Ring of Fire?

Have you ever wondered why it is that certain places – New Zealand, for example; Hawaiʻi; Japan; even the northwest of the US – seem to get so many devastating earthquakes and volcanoes, while other places get none?

The reason, in fact, is simple: as distant from each other as these places are, they’re all linked by the“Circum-Pacific Belt – or, to use its more evocative name, the Pacific Ring of Fire.

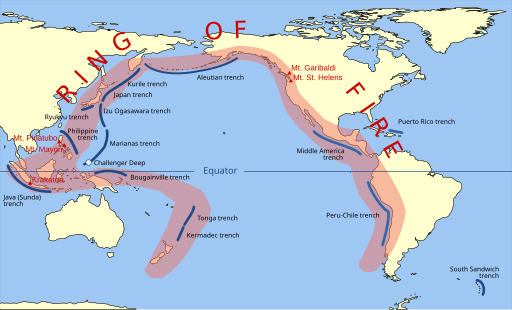

“Made up of more than 450 volcanoes, the Ring of Fire stretches for nearly 40,250 kilometers (25,000 miles),” notes the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Despite its name, the “ring” is actually “in the shape of a horseshoe,” NOAA explains, reaching “from the southern tip of South America, along the west coast of North America, across the Bering Strait, down through Japan, and into New Zealand.”

Okay, we admit, you have to use your imagination even for the horseshoe.

Technically, that’s not even all of them. The Ring of Fire may look like a horseshoe, but that’s only because we can’t see the whole picture: it is possible to close the ring, National Geographic points out, if you include the several active and inactive Antarctic volcanoes.

Even without this extra southern section, however – since whether or not to include Antarctica is something of an ongoing disagreement among geologists – three out of every four of the planet’s volcanoes can be found along the Ring of Fire. It’s the equivalent of one volcano every 88 kilometers (54.7 miles) or so, overall – to put that in perspective, if they really were spread out evenly like that, you could fit six inside the Grand Canyon.

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

Of course, things aren’t so orderly in real life. Take Japan, for example: a tiny nation, all things considered – and yet, thanks to its location within the Ring of Fire, it experiences as much as ten percent of all the world’s volcanic activity.

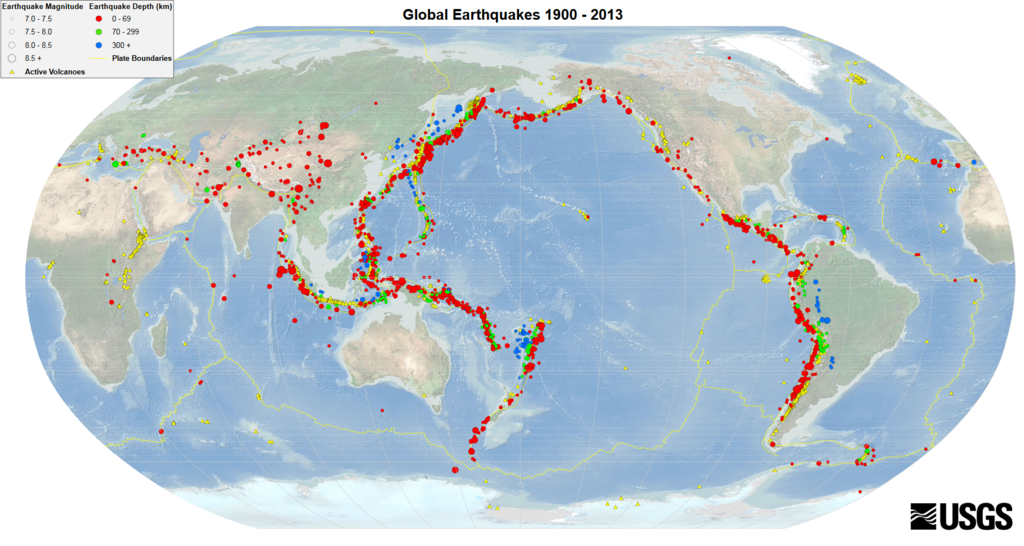

It’s not all volcanoes, though – and the infamous ring has even more of a monopoly on earthquakes. Something like 90 percent of the world’s earthquakes also occur along the Ring of Fire, including the 1960 Valdivia Earthquake in Chile – the strongest ever recorded, reaching a magnitude of 9.5.

What causes the Pacific Ring of Fire?

It’s a question of plate tectonics. If you think of the Earth as a big swimming pool filled with pool toys, you kind of get the idea: the pool toys, standing in for the planet’s lithosphere, or outermost layer, in this analogy, sort of float around on top of the liquid water – which, for the Earth, is the molten rock that makes up its asthenosphere, or the middle bit of the mantle.

Now, mostly, things are pretty stable, with the pool toys getting gently swished around by the water, moving across the pool over time but generally not getting into much trouble. But occasionally, thanks to the differences in how the water and toys can move and interact with each other, you’re going to get bumps. Bashes. Splashes. That kind of thing.

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

It’s the same with the planet. “The lithosphere is broken up into seven very large continental- and ocean-sized plates, six or seven medium-sized regional plates, and several small ones,” explains Britannica. “These plates move relative to each other, typically at rates of 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches) per year, and interact along their boundaries, where they converge, diverge, or slip past one another.”

“Such interactions are thought to be responsible for most of Earth’s seismic and volcanic activity,” it explains. “Plate motions cause mountains to rise where plates push together, or converge, and continents to fracture and oceans to form where plates pull apart, or diverge.”

As it turns out, the Ring of Fire just happens to follow the meeting points of a whole bunch of these tectonic plates: there’s the Eurasian plate; the North American; Juan de Fuca; Cocos; Caribbean; Nazca; Antarctic; Indian; Australian; Philippine plates, and plenty of other, smaller plates too, all of which surround the vast Pacific plate.

The result is… well, it’s what gives the Ring of Fire its name: volcanoes, and earthquakes – and a lot of them. “Much of the volcanic activity occurs along subduction zones, which are convergent plate boundaries where two tectonic plates come together,” explains NOAA. “The heavier plate is shoved (or subducted) under the other plate. When this happens, melting of the plates produces magma that rises up through the overlying plate, erupting to the surface as a volcano.”

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

These subduction zones are “also where deep earthquakes happen,” it continues. “Earthquakes occur as the two plates scrape against each other and as the subducting plate bends.”

That pattern looks familiar, doesn’t it?

The future of the Ring of Fire

What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object? That question may be impossible to answer, but a close estimate might be: in a fight between the biggest ocean on Earth and the Ring of Fire that surrounds it, who would win?

Perhaps incredibly, some experts are putting their money on the Ring of Fire – predicting that, eventually, the Pacific Ocean will entirely disappear. Not from any environmental catastrophe, like so many of its fellow waterways – purely because of the scale of the tectonic activity around it.

“By simulating how the Earth’s tectonic plates are expected to evolve using a supercomputer, we were able to show that in less than 300 million years’ time it is likely to be the Pacific Ocean that will close, allowing for the formation of Amasia,” said Chuan Huang – a researcher at Curtin University’s Earth Dynamics Research Group and lead author of a 2022 paper on the future of the Pacific – in a statement at the time.

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

“The resulting new supercontinent has already been named Amasia,” Huang explained – a portmanteau of America and Asia, the two main constituent landmasses that will form it. But “Australia is also expected to play a role in this important Earth event, first colliding with Asia and then connecting America and Asia once the Pacific Ocean closes.”

What then for the Ring of Fire? Well, it presumably won’t be much of a “ring” anymore – maybe it’ll be called the Great Amasian Zip or something – but one thing’s for sure: it’ll almost certainly still be hot.

Source Link: What Is The Pacific Ring Of Fire?