We live in turbulent times. At every juncture, at least half the country is pissed at the government, complaining that “I didn’t vote for this! What happened to democracy?!” At which point, some smug commentator will pop up and point out, a wry smile on his face as ICE cart him away, that “actually, the US is a republic, not a democracy. Ha, eat it, libs.”

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

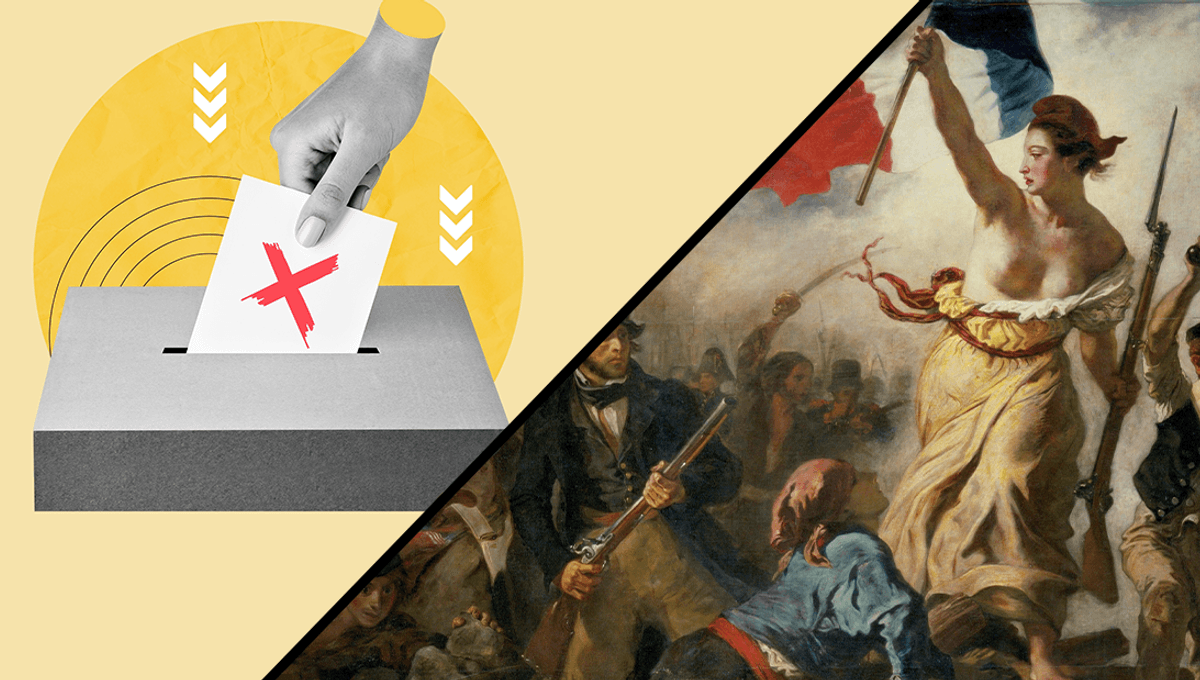

But is this actually true? Don’t Americans, kind of famously, hold elections all the freaking time? Doesn’t that make it a democracy? What’s the real story here?

Well, it’s kind of fuzzy… but the short answer? It’s both. You know – for now.

What is a “republic”?

Despite the many potential examples that might spring to mind when you hear the word – the USA, France, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and so on – a “republic” is really best defined by what it isn’t. So here goes: a republic, basically, is not a monarchy.

We tend to assume such a system must necessarily be a democracy – after all, without a monarch, who else holds the power but the citizenry and those they elect? But just because a society doesn’t have a crown at the top doesn’t mean it’s somehow inherently egalitarian, and it’s totally possible for a republic to be undemocratic. In fact, the prototypical example of one was a full-on aristocracy.

Just ask the citizens of Ancient Rome, from where we actually get the word “republic” – it originated as res publica, or a “public matter”, since, in theory, it marked a move from the Roman Kingdom, under an unelected monarchy, to a system where power was in the hands of the citizenry. In reality, however, the Roman Republic was ruled not by the people so much as some people – specifically, the few who came from the right families and had the right connections.

“You had the Senate […] which actually ran the show, and was comprised of men from the aristocratic (patrician) class,” explained author and historian Philip Matyszak in 2020. “And you also had a lot of democratic forums that, as the Republic evolved, become more meaningless.”

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

And the separation of classes was very real: “Patricians were, if you like, the original aristocratic class of Rome,” Matyszak told History Extra, “and had certain ranks in the Roman aristocracy that were reserved only for them. They got married by particular religious rites, which were separate from those of the general population, and they tended to represent the top families in Rome.”

Even today, you don’t have to look too far for examples of non-democratic republics. Take China, for example – or to use its formal name, the People’s Republic of China. There, opposition political parties are explicitly banned, authorities shun constitutionalism, and democracy in general is presented as kind of short-sighted and potentially dangerous.

It’s a viewpoint that would have found sympathy from Plato – aka the guy who literally wrote the book on republics (it’s called, appropriately, The Republic). In it, he “relentlessly argue[d] against democracy,” explained Matthew Duncombe, an associate professor in philosophy at the University of Nottingham, earlier this month, likening it to a “skilled trade” that “not everyone has the talent or the training to be good at.”

“Imagine if, when passengers boarded a plane, they had a mini election to select one of their number to pilot the flight,” Duncombe wrote. “What if, despite being an excellent pilot, [a candidate] were not able to make their case? What if some other passengers argued that you cannot learn aviation, and that anyone could do it? Or falsely claimed that the pilots were always looking at charts and doing sums and didn’t really care about the concerns of everyday passengers. Or cobbled together the biggest share of the passenger votes through bribes, deals, or lies.”

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

What if, indeed?

What is a “democracy”?

Democracy is exactly what it says – if you know how to look for it. The word is an ancient mashup of two Ancient Greek terms: demos, meaning “the people”, and kratos, meaning “rule”. In other words: rule by the people.

Of course, who counts as “people” has historically been something of a moving target. In Ancient Athens, for example – often seen as the birthplace of the system, although it was hardly alone in its embrace of democracy, and likely not its inventor either – you could vote only if you were an adult, a man, not a slave, and not a citizen of any other state. Overall, that left about 70 percent of the population with no say.

Or take the young USA, in which enslaved black people were (in)famously counted as 3/5 of a person – enough to count for census-taking, but not for voting. It took an entire civil war, nine years of politicking, and a constitutional amendment for Black Americans to get the same rights of suffrage as their white counterparts – and even then, countless state laws were instituted specifically to disenfranchise based on skin color.

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

Occasionally, though, this blinkered view of personhood could backfire. Despite the common story of the American Revolution being a quest for democracy against tyranny, the UK technically had some incredibly progressive democratic principles at the time: “Strictly speaking there [was] no rule preventing women from voting,” explained Tom Schofield, a researcher at Newcastle University and investigator at the Eighteenth-Century Political Participation & Electoral Culture (ECPPEC) project.

“If you meet all the other criteria […] then, technically you could be qualified to vote,” he wrote. “And historians have found evidence of a few women attempting to cast polls.”

Similarly, “there was no legislation blocking black men from casting their votes, provided that they met the other voting qualifications,” pointed out Hillary Burlock, a Research Associate at Newcastle University who also works on the ECPPEC project. We know, in fact, that they did: Ignatius Sancho and George John Scipio Africanus are two whose voting records have been uncovered, and “there are likely to be other examples of black voters to be discovered,” Burlock wrote.

Of course, that’s not to say that the 18th-century UK was a paragon of democracy – but it does at least highlight, once again, that the term is not interchangeable with “republic”. After all, even today the UK is technically ruled by a monarch – and yet, at last count, they’re doing quite a bit better than the US in the old democracy rankings. In fact, the most democratic country in the world – Norway – is a monarchy, and so are four others from the top ten.

So what does this mean for the US?

So, we’ve figured out what democracies and republics are – but which one is the USA?

Well, as you may have inferred by now, the two aren’t mutually exclusive. Just as a state can be a democracy but not a republic, or a republic and not a democracy, it’s equally possible to be both – and, in theory at least, that was the goal in setting up the new US.

“These terms [democracy and republic] are not mentioned in the Declaration of Independence, a document that nevertheless expresses clearly that governments should be established ‘deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed’,” explains Merriam-Webster. “This reads like a definition of both democracy and republic.”

There’s some important context here. Back in the days of the American Revolution, democracy wasn’t seen as an intrinsically good thing – it was actually considered kind of primitive, having been last attempted back in ancient times. It seemed obvious that it would end in mob rule – that’s why the early Americans installed an electoral college, after all – and, ultimately, would lead to the downfall of liberty.

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

Even if they wouldn’t have advocated for it by name, though, their goal was still a form of democracy. “The [words] democracy and republic are frequently used to mean the same thing: a government in which the people vote for their leaders,” explains Merriam-Webster. “This was the important distinction at the time of the founding of the United States, in direct contrast with the rule of a king, or monarchy, in Great Britain.”

“In part because that context was clear to everyone involved in the American Revolution, democracy and republic were used interchangeably in the late 1700s,” it adds. “Both words meant that the power to govern was held by the people rather than a monarch.”

So, there it is: the US is – in theory, at least – both a democracy and a republic. Always has been. And, at least until a certain president declares himself hereditary dictator for life, it should continue to be.

Source Link: What's The Difference Between A Republic And A Democracy (And Which Is The US)?