We need to take the popular belief in alien visitations seriously, one researcher has argued – not because it could be true, but rather because that credence can be very harmful.

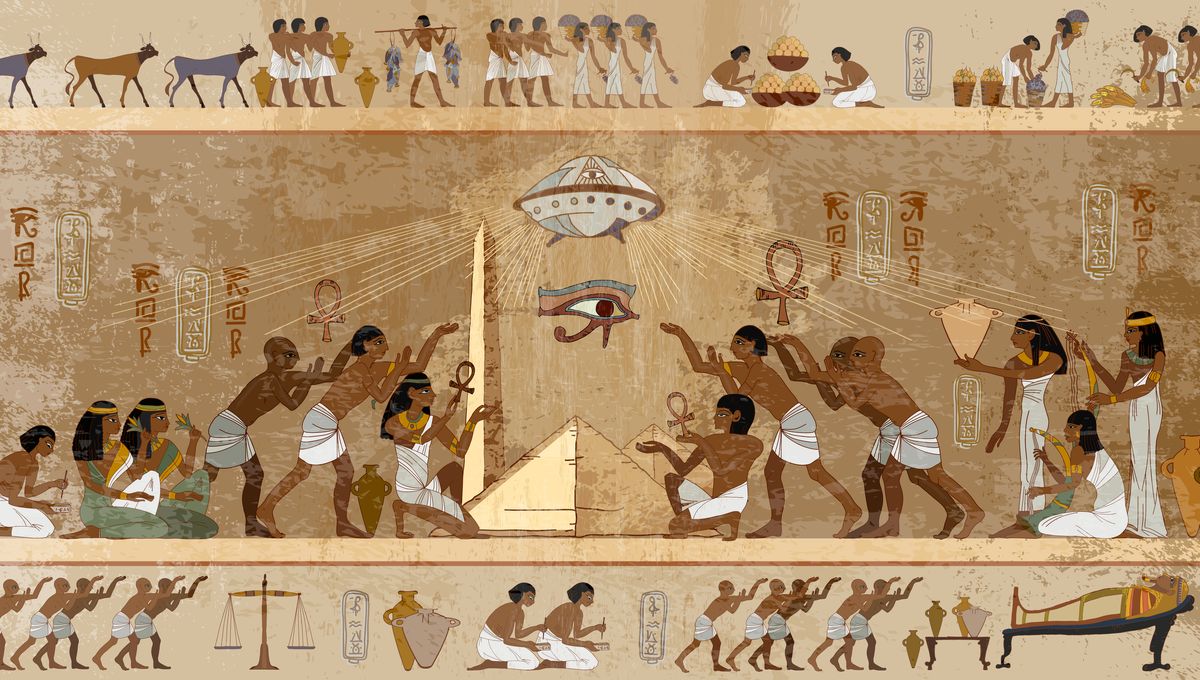

The beliefs that extraterrestrial spacecraft buzz in our skies, and that past visitors provided ancient civilizations with much of their technologies, have attracted wide support. When it comes to the ancient civilizations side of this coin, there is no evidence that is not either blatantly fraudulent or easily explained by other means.

When it comes to modern UFO sightings, people have certainly reported lights moving in ways no one has yet been able to explain, and some of these observers are credible. Nevertheless, it’s a big leap from; “We don’t know what this is” to “Another species crossed many lightyears of space to nip around in Earth’s atmosphere just enough to draw our attention without leaving anything tangible.”

Many may question whether the popularity of these ideas matters, however. False claims and conspiracy theories can do great harm when they concern vulnerable communities, like religious or ethnic minorities. It’s not so obvious why we should care about a belief in aliens. Dr Tony Milligan of Kings College London thinks there are good reasons to consider the effects of these beliefs and hopes to advance discussion about how to respond.

Perhaps the most obvious point Milligan makes is that the ancient aliens claims are inherently racist and create background harm as a result. The origin for these tales lies in disbelief by people of European descent that people they considered primitive could have achieved impressive feats on their own. If white people hadn’t managed to build the pyramids of Egypt or Central America, or erecting the stone monoliths of Rapa Nui, then how could those they considered savages have managed it? Rather than acknowledge that non-white peoples were just as smart as them – and at certain points in time more technologically advanced – pseudo-historians preferred to claim they must have had help.

Books and “documentaries” on the topic have become exceptionally lucrative, and inspired numerous successors, some of whom may be motivated more by money – Milligan notes that one Youtube channel on the topic has run for 20 years and has almost 14 million subsrcibers. Modern versions attempt to cover up the racism, but the idea continues to undermine of the achievements of non-white societies, making it look like only the Ancient Greeks and Romans invented anything for themselves. Discrediting the achievements of ancient civilizations is an essential step to treating their descendants as inferiors.

Milligan also argues that these inventions interfere with our recognition of Indigenous origin narratives, harming cultures that have often been pushed to the edge of extinction’s capacity to tell their own stories.

Milligan is also concerned about modern day alien stories, particularly when they become so widespread that governments decide they need to respond, opening up records without satisfying those alleging cover-ups. He argues these tales can also “Generate background noise which impedes science communication.” It’s hard to teach people the speed of light may be an absolute limit if they think extraterrestrials are jaunting between stars to spook the locals.

Potentially, Milligan argues, we may need a scientific research program (SRP) to address these claims, rather than ad hoc debunking. Although Milligan is not sure belief in aliens is so widespread and harmful that such a program is required, he has written a paper attempting to assess what would justify an SRP and how it might be done. “If we are underwhelmed by what has been offered as evidence, then we may owe a story about what would count as convincing evidence,” he argues.

Nevertheless, Milligan acknowledges there are problems with trying to construct an SRP on a topic where so many of those pushing the beliefs are uninterested in evidence. Some aspects of claims about aliens can be investigated in ways that can be scientifically productive. Milligan offers an example of suggestions Oumuamua’s path might indicate it was a derelict alien space craft. While the idea, and the confidence with which it was stated, frustrated many astronomers, efforts to find a more plausible explanation deepened our understanding of Oumuamua’s composition.

In contrast, however, many claims don’t lend themselves to being studied in the same way. Insistence that similarities in architecture between distant civilizations must mean they all had common teachers can’t really being addressed by investigations of building methods. There’s not always an easy way for science to respond to pseudo-science, but fortunately people seldom go into science to do something easy.

Milligan’s paper is to be published in the Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, and a preprint is available here. An accompanying Conversation article focuses on the reasons he considers widespread belief a threat.

Source Link: Why A Philosopher Is Worried About People Believing Aliens Have Visited Earth