An enormous area of the Earth’s crust has torn and slumped, dropping about 5 kilometers (3 miles). We’ve only just noticed because this is happening beneath the Pacific Ocean, but what sounds alarming could eventually end one of the planet’s most dangerous earthquake fault lines.

The San Andreas Fault gets most of the USA’s attention when it comes to geologic hazards, but it’s the fault line that doesn’t keep triggering earthquakes that can be most damaging. Off the coast of Oregon and Washington, the Cascadia Subduction Zone moves rarely, leaving more time for pressure to build up into something major. A tsunami around 300 years ago, triggered by a Cascadia quake, would be devastating if replicated today, and there are reasons to think a devastating one is brewing.

Cascadia and the San Andreas are both products of the westward motion of the North Atlantic plate, pushing down oceanic crust in subduction zones – where one tectonic plate slips under another – in the process. These subduction zones are the reason continents change their position on the Earth, creating most of our earthquakes and volcanic eruptions in the process. We still only have a limited understanding of how they form and end.

“Getting a subduction zone started is like trying to push a train uphill – it takes a huge effort,” said Dr Brandon Shuck of Louisiana State University in a statement. “But once it’s moving, it’s like the train is racing downhill, impossible to stop. Ending it requires something dramatic – basically, a train wreck.” Sisyphus could relate, but geologists have not had much opportunity to see what form that trainwreck might take.

Extensive collection of high-resolution images of the sea floor off the Pacific Northwest as part of the 2021 Cascadia Seismic Imaging Experiment (CASIE21) may have changed that.

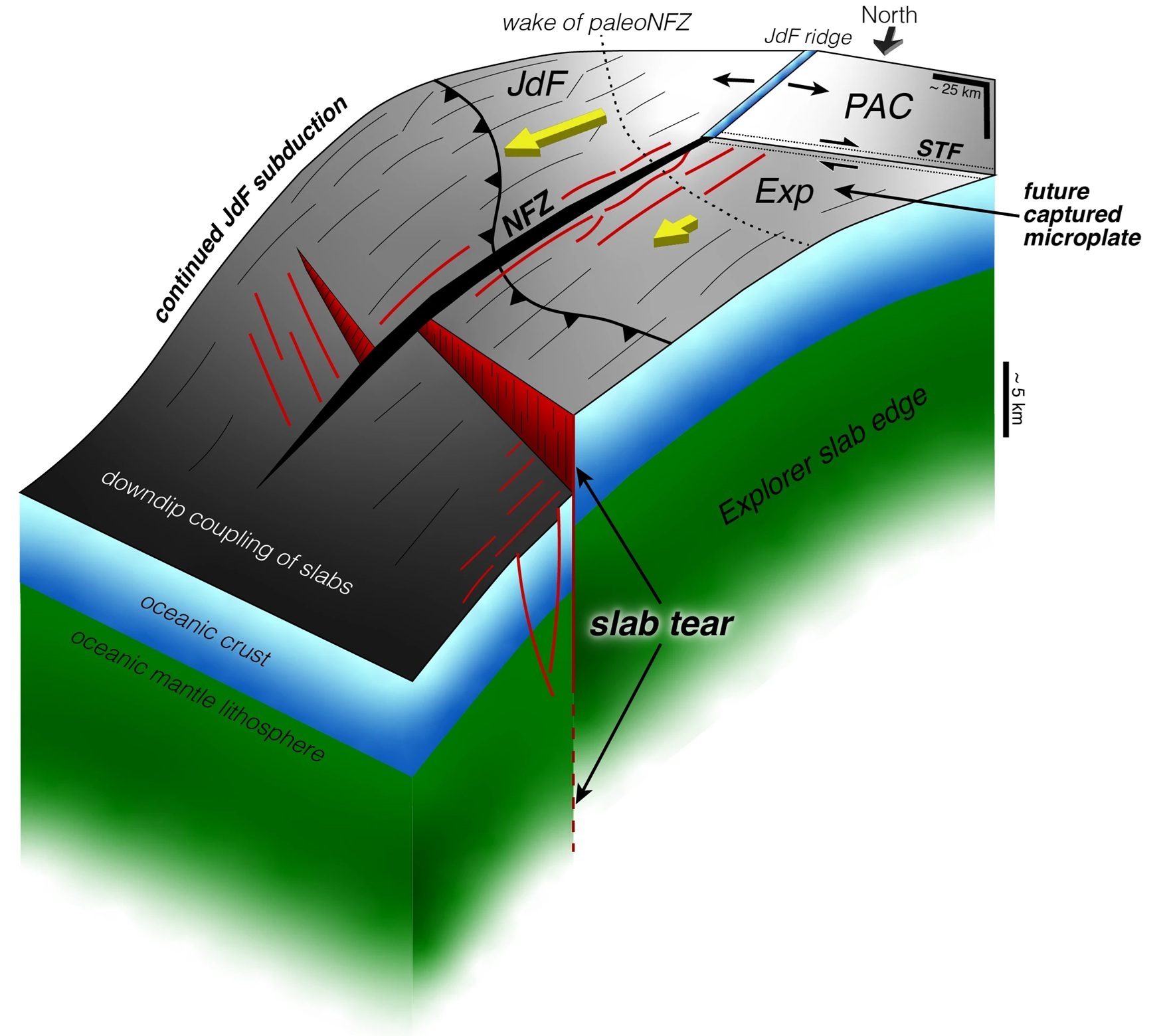

The Cascadia subduction zone, where the North American plate overrides the Juan de Fuca and Explorer plates, is gradually shutting down with slabs breaking off while the remaining plate continues to subduct.

Image Credit: Shuck et al., 2025, Science Advances

“This is the first time we have a clear picture of a subduction zone caught in the act of dying,” said Shuck. “Rather than shutting down all at once, the plate is ripping apart piece by piece, creating smaller microplates and new boundaries. So instead of a big train wreck, it’s like watching a train slowly derail, one car at a time.”

That’s made the area where the North American Plate rides over the Juan de Fuca and Explorer plates complex and jumbled. In one place, the slab has dropped about 5 kilometers (3 miles). “There’s a very large fault that’s actively breaking the plate,” Shuck explained. “It’s not 100% torn off yet, but it’s close.”

Violent as this sounds, Shuck noted, “Once a piece has completely broken off, it no longer produces earthquakes because the rocks aren’t stuck together anymore.” Music to the ears of disaster planners in the two states. Faults known as transform boundaries slice sections of the plate off at right angles to the tear, halting earthquakes in the pieces that have separated.

Shuck and colleagues conclude that the loss of these pieces drains the plate of momentum and eventually stops the subduction process, ending the threat to the region, although creating an opportunity for movement to start elsewhere.

The team thinks what they witnessed is a live version of what ended the subduction zone off Baja California millions of years ago, leaving a legacy of fossil microplates geologists have struggled to interpret.

This process of slab division doesn’t just initiate randomly; it’s caused by a subduction trench getting close to a mid-ocean ridge. The most famous mid-ocean ridge lives up to its name by neatly splitting the distance between the Americas and Europe/Africa. The northern Pacific has no equivalent; instead, there are the Explorer and Juan de Fuca Ridges, lying a few hundred kilometers off the coast of the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia.

The slicing of a slab into pieces isn’t an entirely pacifying process. It can drive bursts of volcanic activity in areas where hot mantle rises around the descending slab pieces. “It’s a progressive breakdown, one episode at a time,” said Shuck. “And it matches really well with what we see in the geologic record, where volcanic rocks get younger or older in a sequence that reflects this step-by-step tearing.”

The region is already marked by active underwater volcanoes, but they’re much less dangerous than the occasional enormous earthquake and tsunami, and a rich source of nutrients besides. Unfortunately for those living uncomfortably close to Cascadia, the process takes millions of years. However, even if the slab tearing will not make the area safe on human timescales, understanding it might give seismologists a better chance of identifying the warning signs, if there are any, before a dangerous quake.

The study is open access in Science Advances.

Source Link: Why An Eastern Pacific Tear In Earth’s Crust Could Spare The Pacific Northwest… Eventually