Deep in interstellar space, about five times farther from us than Pluto, a message is waiting to be heard.

It’s found on a pair of golden disks, decorated with dates and instructions, and containing natural sounds and greetings in dozens of languages, which were sent away from our planet in 1977 in the hope that maybe, someday, someone out there might find them. And the progenitor of these disks? Carl Sagan.

Carl Sagan was a TV presenter – but he was also a prolific writer, both of academic and nonacademic works; he was an activist against nuclear war and for cannabis use; he’s seemingly almost personally responsible for the careers of his successors like Neil DeGrasse Tyson. He pioneered the entire field of astrobiology – the study of life in the universe – and was a champion of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI.

And that’s barely scratching the surface of his legacy.

A media star

Sagan is, of course, most famous for his Cosmos series on PBS, and for good reason: between 1980 and 1990 the show was the most-watched series in the history of American public television, being seen by at least half a billion people across 60 countries.

It is, on its own, an output that “has inspired generations of scientists and brought an appreciation of science to countless nonscientists,” wrote Jean-Luc Margot, Professor of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a 2024 article for The Conversation.

Sagan brought a scientific outlook to the world, promoting critical thinking and rationality in the face of pseudoscience and chauvinism. He co-founded The Planetary Society, and engaged in countless interviews, articles, and public outreach to bring science and scientific thinking to everyday people.

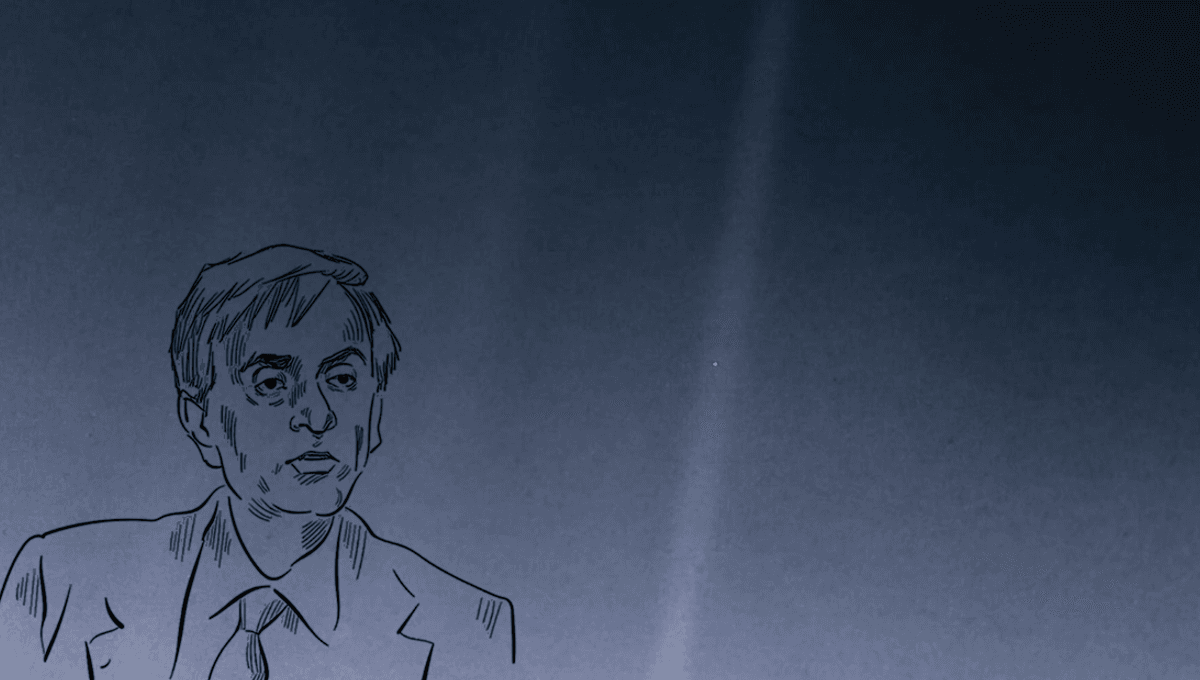

That didn’t always make him popular among academic scientists – despite a prolific output, he was rejected by the National Academy of Sciences due to the “jealousy” of his purported colleagues, a “failure [which] remains an enduring stain on the organization,” according to Margot. But it can’t be denied that he knew how to make a point: it was he who, in 1990, requested that the Voyager 1 space probe took the photo now known as “Pale Blue Dot”.

“Consider […] that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us,” he would later write of the speck in the image. “On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every ‘superstar’, every ‘supreme leader’, every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

“Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light,” he wrote. “Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.”

A scientific legacy

As famous as he was as a media personality, Sagan was a real scientist too: he had more than 600 scientific papers to his name, and was awarded 22 honorary degrees on top of his real BA, BS, MS, and PhD from the University of Chicago.

And his academic work spanned fields of study in a way few other researchers can boast. “He produced notable results and insights,” Margot noted, and had “unusual breadth in astronomy, physics, chemistry and biology.”

“He enabled new scientific disciplines to flourish,” he wrote, “push[ing] forward the nascent discipline of astrobiology – the study of life in the universe.”

Early on in his career, he was one of the first people to understand the atmosphere of Venus. Back in the 1960s, it was assumed that our “sister planet”, as it was known back then, most likely had a climate similar to Earth’s tropics – but Sagan thought something very different was going on. Knowing that the Venusian atmosphere was overwhelmingly composed of carbon dioxide, he proposed a runaway greenhouse effect – one that would result in surface temperatures hundreds of degrees hotter than any (currently) on Earth.

Because of this expertise, he worked with NASA on their Mariner 2 project – the first robotic space probe ever to report back from a planetary encounter. He didn’t get everything he wanted out of the project, but even in his losses it was evident that he possessed a vision rarely seen even in other astrophysicists: “There were those who maintained that cameras weren’t really scientific instruments, but rather catch-as-catch-can, razzle-dazzle, pandering to the public, and unable to answer a single, straightforward, well-posed scientific question,” he would later recall in his 1996 book Pale Blue Dot.

But he knew the value of the visual – not just to the public, but also to scientists who might potentially be too confident in their own knowledge. “I argued that cameras could […] answer questions that we were way too dumb to even pose,” he wrote. “At any rate, no camera was flown.”

Environmental advocacy

Venus having been explored, Sagan next turned his attention to Mars. He “proposed a compelling explanation for seasonal changes in the brightness of Mars, which had been incorrectly attributed to vegetation or volcanic activity,” Margot wrote. “Wind-blown dust was responsible for the mysterious variations, he explained.”

But of course, any old visionary scientist can rewrite what we know about extraterrestrial planets like Venus or Mars. What set Sagan apart was his ability to see his discoveries not merely as interesting facts about other planets, but as cautionary tales for our own.

“The amount of CO2 in the Venus[ian] atmosphere is much larger than here,” he announced in his 1985 testimony to the US Congress. “But it is an indication of what can happen in an extreme case.”

“[With] the present rate of burning fossil fuels,” he warned, “there will be a several centigrade degree temperature increase of the Earth’s global average by the middle to the end of the next century. That has a variety of consequences, including redistribution of local climates, and the melting of glaciers, and an increase in sea level – there is concern, on a somewhat longer time scale, about the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet and a [sea level] rise of many, many meters.”

“Here is a problem which transcends our particular generation,” he said. “It is an intergenerational problem. If we don’t do the right thing now there are very serious problems that are children and grandchildren will have to face.”

Now, 30 years later, we’re only just coming to terms with how right he was.

A global consciousness

When your work offers a perspective that stretches light-years and eons, it’s difficult to keep a closed mind on topics outside of your nominal expertise. For Carl Sagan, that meant not only inspiring people to take an interest in science, but also promoting international peace and co-operation in a period defined by icy tension.

At a time when world politics basically involved a threat of wiping out all life on Earth at the drop of a wrench socket, Sagan was one of the most prominent voices calling for nuclear disarmament: “He was an antinuclear activist and spoke out against the Strategic Defense Initiative, also known as ‘Star Wars’,” noted Margot. “He urged collaborations and a joint space mission with the Soviet Union, in an attempt to improve US-Soviet relations.”

Global warming, too, was a problem urgent enough to require a global restructuring away from the war-posturing of his time: “I think that what is essential for this problem is a global consciousness view,” he told the assembled senators; “[one] that transcends our exclusive identifications with the generational and political groupings into which by accident we have been born.” And in his trademark way, he didn’t only address Congress and other academics about this, penning essays in Parade magazine to reach lay audiences of tens of millions of people.

It was a stance that didn’t always make him popular, either among his peers or the government. He was accused by some scientists of being a propagandist, basing strong statements on comparatively wobbly science – specifically, for example, his promotion of the idea that nuclear war would necessarily cause a devastating “nuclear winter” – and he found himself arrested multiple times for anti-nuclear weapons activity.

Evidently, though, he thought it was worth it. After all, there’s only one Earth – and as important as we think our own country, tribe, or community may be, in the end, we’re all just a pale blue dot in space.

Source Link: Why Carl Sagan Was Way Ahead Of His Time And The Legacy He Left Behind