“Comets are like cats,” David H Levy said, “They both have tails and do precisely what they want.” As co-discoverer of many comets – including Shoemaker-Levy 9, made famous for smashing into Jupiter before the eyes of the world – Levy should know. The saying is popular among astronomers watching one comet after another fail to live up to their hopes for peak brightness or trying to keep their optimism for a new one in check. Three years ago, however, one comet did something more like a dog than a cat, giving its tail a sold wag. The explanation may lie in a well-timed coronal mass ejection from the Sun.

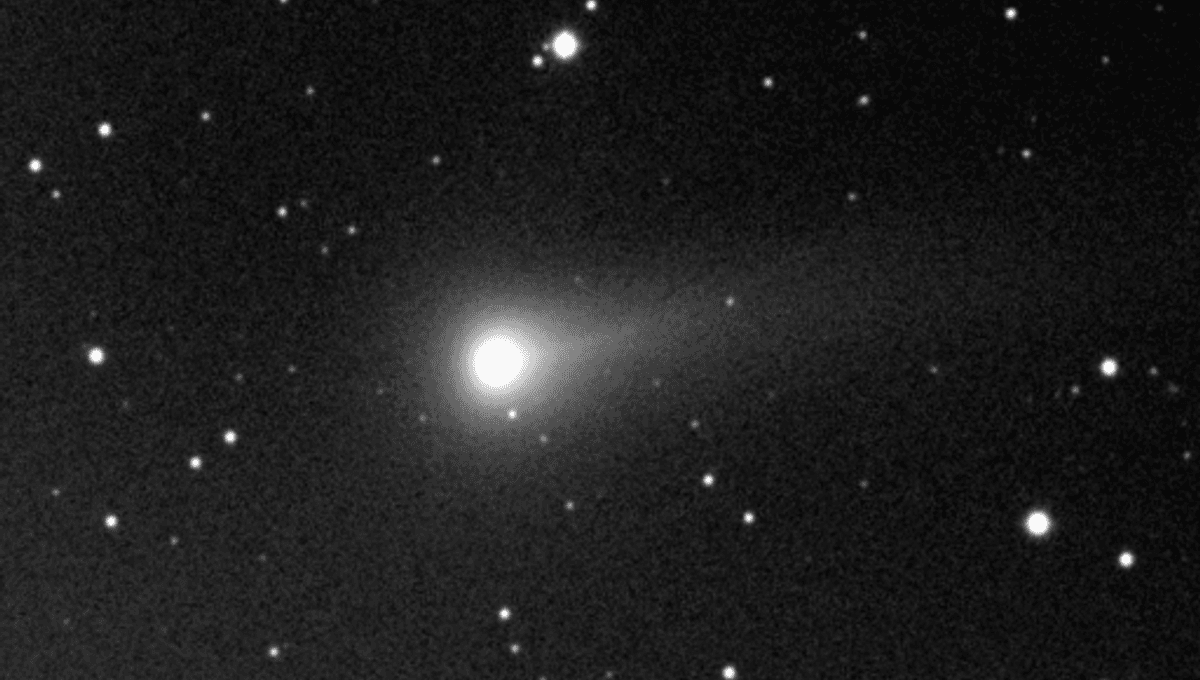

Comet C/2020 S3 (Erasmus) has an orbit lasting 1,800 years. If anyone saw its 3rd-century visit, their observations are lost in time. When spotted in September 2020, it seemed like a typical long-period comet, albeit one that had snuck up on us, and would soon venture as close to the Sun as Mercury’s orbit.

At its brightest, Erasmus was close enough to the Sun from our perspective that it was difficult to observe, but the STEREO-A and SoHO spacecraft were better positioned and provided data that has proven useful to astronomers.

In a behavior more common in comets than pets of either variety, Comet Erasmus grew two tails – one of dust and one of ions – which did not always point the same way.

When closest to the Sun, 12 metric tonnes of water vapor streamed off Erasmus every second as its ice turned to gas. Dust previously bound up with this ice escaped as well.

There is a myth that comet tails always trail behind them, and a partially true belief that they are pushed away from the Sun by the solar wind. In fact, a team led by Professor David Jewitt of UCLA notes, the dominant force in determining cometary dust tails is radiation pressure, which pushes on the escaping dust at least ten times harder than the solar wind does.

Some of the water vapor leaving Comet Erasmus became ionized by ultraviolet light, and the plasma formed from these ions could also be seen by the spacecraft. For the plasma tail, the solar wind is the primary force shaping its direction.

Dust tails are curved, sometimes quite visibly so, by the comet’s motion. Plasma tails, while pointing closer to directly opposite the Sun, can show fine structure, reflecting shifts in the solar wind. Indeed, this is how the solar wind was first discovered, and we can learn how it is changing by watching comet tails’ movement.

No well-recorded comet tail has ever shown quite the swish of Comet Erasmus, however. Its tail swung from 150° to 210° relative to the Sun over 11 days, implying variations in the speed of the solar wind from 200 to 550 km/s (450,000-1,200,000 Mph). At one point it swung so widely it can only be explained by a component of the solar wind not traveling radially away from the Sun.

Such non-radial solar winds have been observed before in other ways, and attributed to several causes. The most common, and the one Jewitt and co-authors think is likely to be responsible here, is a large Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) associated with a sunspot. Because the CME in question was pointed away from the Earth, we barely know of its existence.

The paper has been submitted to the Astronomical Journal, but has yet to be approved. A preprint is available on ArXiv.org

[H/T New Scientist]

Source Link: Why Comet Erasmus Wagged Its Tail