If you’ve ever counted beyond ten, and we’re going to be generous and assume that you have, at some point you’ve probably noticed the names of the numbers are a little odd.

While we say “thirteen”, “fourteen”, “fifteen”, “sixteen” and so on, when it comes to 11 and 12, we don’t say “oneteen” or “twoteen”, or any variation thereof. For some reason, 11 and 12 get their own words: eleven and twelve. Why is this? It likely all has to do with base 10 and the arguably more useful base 12.

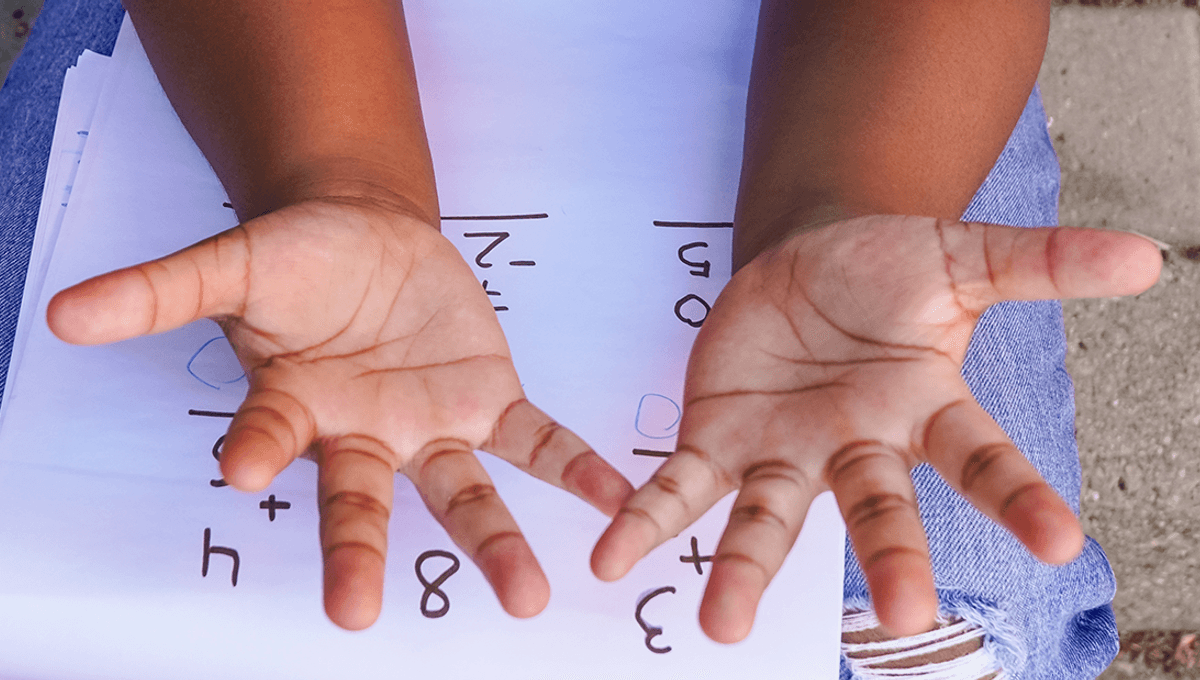

Modern humans tend to use base 10, where digits go 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and then 10. Rather than being mathematically superior, this likely comes down to the number of digits on our hands; we’ve got 10 of them. But there’s no reason why you can’t use other bases, base 3, base 12, base 60, to name three numbers.

In base 12 (or the duodecimal system), for example, you would just need a few extra numbers to denote ten and eleven, with 12 occupying the number 10. So it would go 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X, Ɛ, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 1X, 1Ɛ, and so on, if you use the Dozenal Society’s notation.

“The special position occupied by 10 stems from the number of human fingers, of course, and it is still evident in modern usage not only in the logical structure of the decimal number system but in the English names for the numbers,” Encyclopedia Britannica explains. “Thus, eleven comes from Old English endleofan, literally meaning ‘[ten and] one left [over],’ and twelve from twelf, meaning ‘two left’; the endings -teen and -ty both refer to ten, and hundred comes originally from a pre-Greek term meaning ‘ten times [ten]’.”

Tracing this back further to old Germanic languages, this becomes ainlif and twalif.

“Ainlif, twalif, which, it is generally agreed, mean something like ‘(ten and) one left over’ and ‘(ten and) two left over’ respectively,” a paper on the topic of Germanic numerals explains. “These are clearly distinguished in mode of formation from the numerals thirteen to nineteen, which are dvandva compounds.”

Though it’s not entirely clear, there is evidence that the special names for 11 and 12 stem from base 12 being used by our ancestors, or at least being influenced by it. This base is useful because of how divisible it is, and though we generally use base 10, we still regularly (and throughout history) group things into twelves, such as inches, and use “dozen” to denote 12. Overcounting (10 and one left over, 10 and two left over) may have hung around as we continued to break numbers up into groups of 12, even if we didn’t use 12 as a base.

There is evidence in old Germanic languages that indicates that base 12 may have been used, for instance, the Old Norse word “hundrað” actually meant 120, 12 groups of 10 instead of 100.

“A second piece of evidence is that in the earliest texts written in Germanic languages (such as the Gothic Bible), there are notes in the margins explaining to readers that certain numbers should be read “tenty-wise”, or in the base-10 counting system. These notes wouldn’t be necessary in a society that already consistently counted by tens,” Danny Hieber, who has a PhD in linguistics, explains on his blog Linguistic Discovery.

“The reason the overcounting stops at 12 seems to be that early duodecimal influence. *ainalif became endleofan in Old English, and that developed into the Modern English word eleven, while *twalif eventually became ‘twelve’,” Hieber added.

Source Link: Why Do We Say "Eleven" and "Twelve" Instead Of "Oneteen" And "Twoteen"?