Between plagues, wars, and freakishly cold weather, the early modern period was not the best time to be a human in England. For women in particular, there was another ever-present threat to contend with: allegations of witchcraft. But why were so many more women than men accused of practicing the dark arts? A new study has looked back into the annals of history and suggests that one major factor could have been their jobs.

Witch trials became something of a feature of public life during the 16th and 17th centuries, most famously in the British Isles and New England, but there was a very clear gender bias at play: only around 10-30 percent of the accused were male. Misogyny is, of course, a big reason for this, but a new analysis from University of Cambridge Assistant Professor Philippa Carter has brought some fresh insights.

Carter turned to the casebooks of Richard Napier, a prominent English medical practitioner and astrologer who operated between 1597 and 1634. During his career, he’s known to have performed almost 70,000 separate consultations, a small fraction of which dealt with suspicions of witchcraft and bewitchment.

“While complaints ranged from heartbreak to toothache, many came to Napier with concerns of having been bewitched by a neighbour,” Carter explained in a statement. “Clients used Napier as a sounding board for these fears, asking him for confirmation from the stars or for amulets to protect them against harm.”

Among 802 of Napier’s clients who mentioned suspected witches by name, 130 also gave details about the accused’s occupation, and as Carter analyzed these records, some themes began to emerge.

The case notes regularly featured six types of jobs that were almost exclusively performed by women: food services; healthcare; childcare; household management; animal husbandry; and dairying.

These jobs gave the women who held them a certain amount of power in the community, but also a lot of responsibility, and that often led to suspicion against them.

“An early modern housewife was responsible for managing the health of livestock as well as humans; she made the poultices and syrups used to treat both. When an animal sickened strangely, this could be interpreted as a malefic abuse of her healing skills,” said Carter.

“Natural processes of decay were viewed as ‘corruption’. Corrupt blood made wounds rankle and corrupt milk made foul cheese. Women’s work saw them become the first line of defence against corruption, and this put them at risk of being labelled as witches when their efforts failed.”

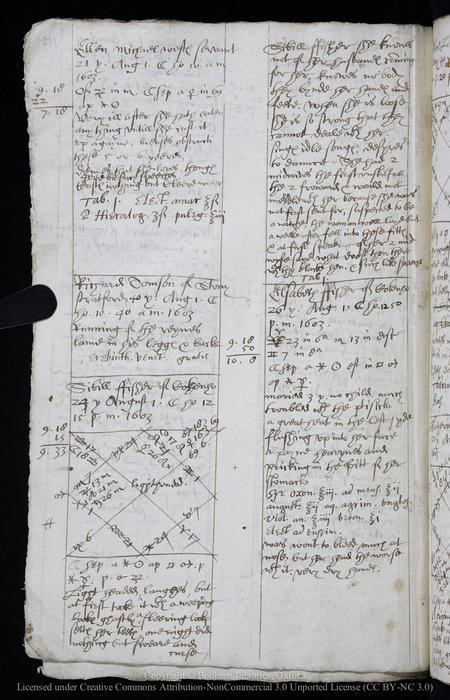

Human healthcare and midwifery during this time period was an especially risky business, which was – as it still is today – dominated by women. One of Napier’s cases from 1603 tells the story of Sybil Fisher of Cogenhoe, a 24-year-old who suffered delirium after giving birth. As Napier noted, a cloud of suspicion hung over one of the unfortunate woman’s midwives.

The page from Napier’s casebook where he recorded his consultation on the case of Sybil Fisher.

Image credit: Bodleian Library

“She had 2 midwives, the first unskilful, the 2nd froward (grumpy) & would not meddle with her because she was not first sent (for). Her suspected to be a witch. The woman well laid but a week after fell into these fits & at first speaking of her 2nd midwife said ‘what doest thou there with thy black hen?’ & such like speeches.”

Carter explained how these accused women were often in the wrong place at the wrong time. “The frequency of social contact in female occupations increased the chance of becoming embroiled in the rifts or misunderstandings that often underpinned suspicions of witchcraft. Many accusations stemmed from simply being present around the time of another’s misfortune.

“Women often combined multiple income streams, working in several households to make ends meet: watching children, preparing food, treating invalids. They worked not just in one high-risk sector, but in many at once. It stacked the odds against them.”

Carter’s work provides another compelling reason why women figured so much more than men in the moral panic around witchcraft that was ultimately responsible for hundreds of executions – a particularly timely finding as we head towards spooky season.

“Every Halloween we are reminded that the stereotypical witch is a woman,” Carter concluded. “Historically, the riskiness of ‘women’s work’ may be part of the reason why.”

The study is published in the journal Gender & History.

Source Link: Why Were So Many Women Accused Of Witchcraft? Maybe Because Of Their Jobs