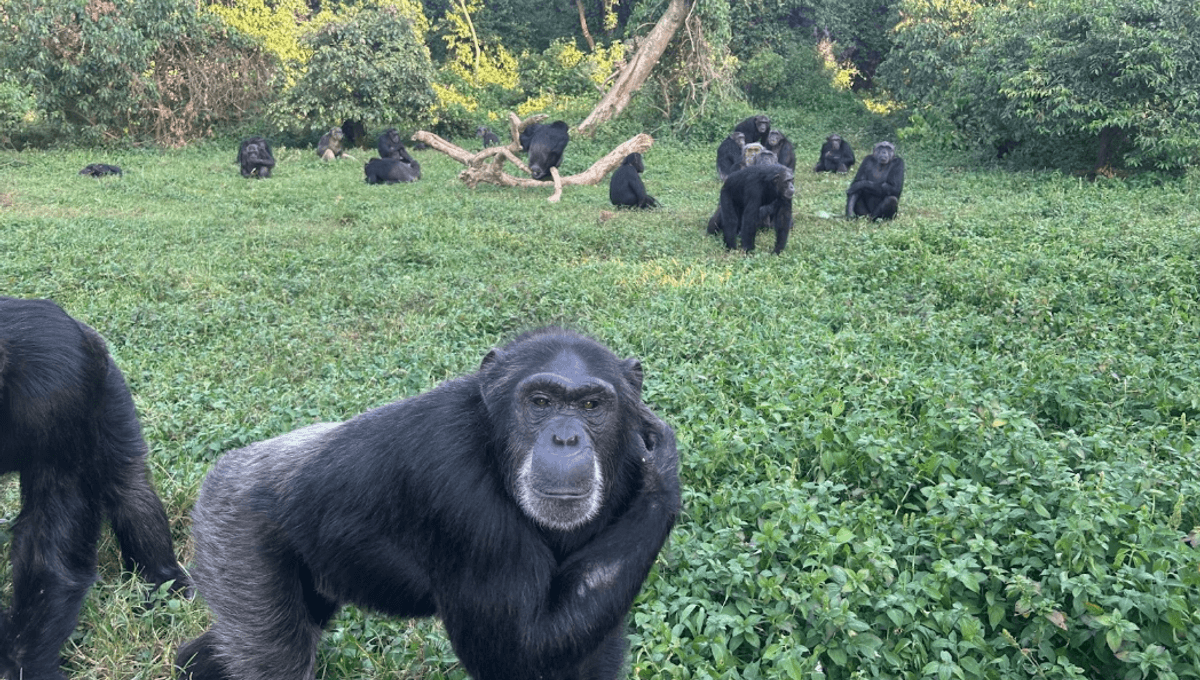

Chimpanzees at Uganda’s Ngamba Island Sanctuary can do what was once considered an exclusively human trait: form expectations on the basis of evidence, but revise them on learning new facts. Responding to evidence is an essential skill for the survival of any animal, but given how often humans neglect our supposed superpower, seeing another species show such sophisticated processing is somewhat humbling.

When the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson was criticized for differences between editions of his textbook, he responded, “When events change, I change my mind. What do you do?” (often misattributed to John Maynard Keynes). The question might have been rhetorical, but we’re all familiar with people who appear unable to alter their beliefs no matter what new facts emerge, perhaps sometimes even ourselves.

To see how our nearest relatives do on this account, Dr Emily Sandford of UC Berkeley and colleagues put food in one of two boxes and gave chimpanzees clues as to which held the reward. Sanford wanted to make sure the chimpanzees were not only able to change their mind about which box to open, but that they could weigh the quality of evidence, rather than just going on whichever had been presented more recently.

“We recorded their first choice, then their second, and compared whether they revised their beliefs,” Sanford said in a statement. “We also used computational models to test how their choices matched up with various reasoning strategies.”

The results indicated the participants could not only recognize if the facts had changed, but also if that change was large enough to warrant a shift in approach, potentially making them rational thinkers.

“Chimpanzees were able to revise their beliefs when better evidence became available,” Sanford said. “This kind of flexible reasoning is something we often associate with 4-year-old children. It was exciting to show that chimps can do this, too.”

Chimpanzees, like us, being visual creatures, the strongest evidence came in the form of seeing food inside a box. Sounds from the box were treated as intermediary, and traces of food in a box’s vicinity were the weakest sign.

Chimpanzees are not infallible, but they picked the rational choice two to three times more often than the nonrational one across five differently structured experiments. This included relatively complex situations, such as when the team provided new evidence that undermined the credibility of the first information the chimps had been given, for example, showing what looked like an apple might just be a picture.

Another experiment offered the chimps strong evidence for a single treat in a box, against weak evidence for two treats in another. They found that the chimpanzees do not agree with the human proverb, “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” Never take a chimp’s advice at a casino if you don’t want to lose your shirt.

The authors write, “Our findings present strong support for the view that chimpanzees have genuine metacognitive capacities.” That is, thinking about thinking.

By extending the research to other primates, the work may help us determine when in our evolutionary history such reasoning powers developed.

“The difference between humans and chimpanzees isn’t a categorical leap. It’s more like a continuum,” Sanford said. To understand that continuum better, Sandford is conducting similar experiments on children between the ages of two to four. “It’s fascinating to design a task for chimps, and then try to adapt it for a toddler,” she said.

Philosophers and scientists have debated for millennia if animals think. Most would now agree that many species do, but some would argue the answer depends on how one defines thinking. Yet this research suggests that at least one species meets possibly the highest test of thinking, the capacity to reason by weighing the significance of evidence.

As Professor Brian Hare of Duke University notes in an accompanying Perspective, Darwin “Predicted that psychological elements would be found in nonhumans, particularly in nonhuman apes, that bridge the gap between human and nonhuman cognition.” It’s hard to see what more we could ask apes to do to meet that prediction.

The study is published in Science along with the accompanying Perspective.

Source Link: Chimps Can Revise Beliefs When Confronted With Conflicting Evidence. Can You?