Observations from six spacecraft and some of the most powerful telescopes on Earth have revealed that temperatures change in Jupiter’s atmosphere much more than we would expect. Astronomers who have tracked these movements have shown distant regions appear to be “teleconnected”, with shifts in one being reflected far away with no obvious effects in between.

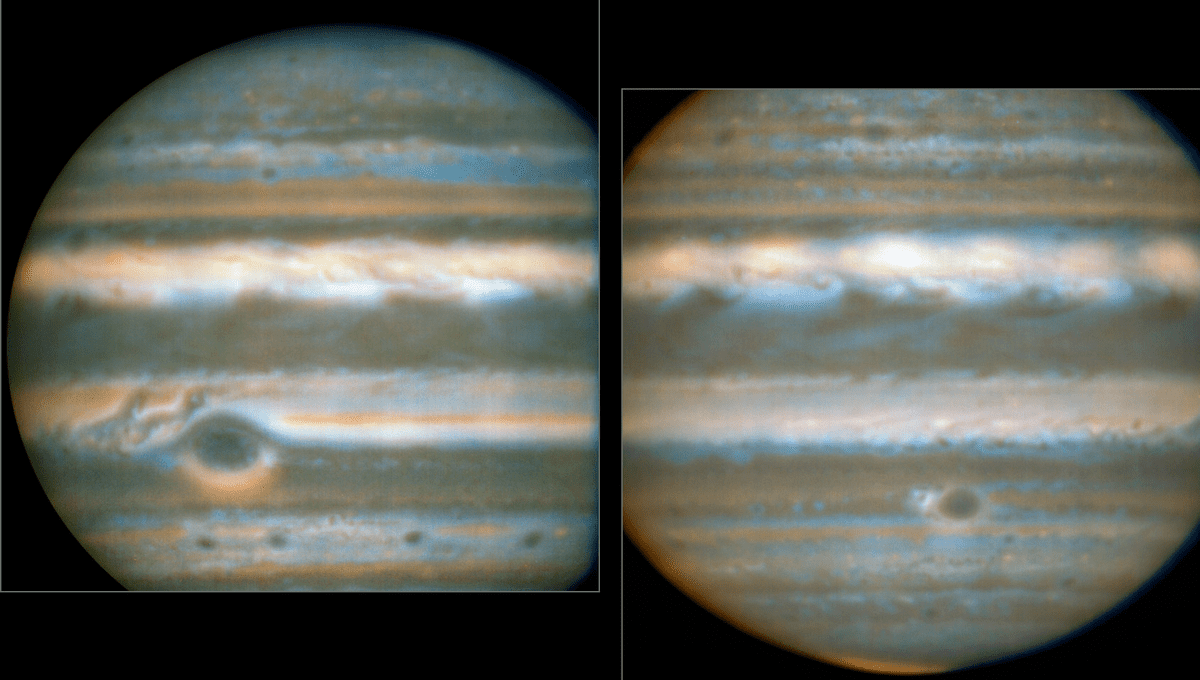

It wasn’t long after Galileo first turned his telescope to Jupiter that people noticed the alternating bands of white and reddish-brown running parallel to the equator. Even Pioneer 10 and 11, exceptionally primitive spacecraft compared to what was to come, were able to tell the white bands were colder than the dark ones.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Dr Glenn Orton set out to understand why, including finding out how the temperatures of the bands varied with time. He’s been studying the problem ever since. Now, along with co-authors who were not born when the research began, Orton reported significant progress in Nature Astronomy.

Most of Jupiter is gas, but it has layers that don’t mix much, some of which are designated the troposphere and stratosphere, after the atmosphere on Earth, rather than Jupiter proper.

Although the temperature of the troposphere varies by band, astronomers initially didn’t expect much movement between seasons. Jupiter’s orbit is highly circular and with an axis tilted by just 3°, compared to 23° on Earth, meaning the hemispheres get almost equal light exposure at any time.

Nevertheless, as more spacecraft visited the giant planet, and telescopes were built that could measure temperatures at specific locations from hundreds of millions of kilometers away, Orton and colleagues collected an impressive dataset on Jupiter’s temperature by band and month. Cycles have emerged lasting four, seven to nine, and 10-14 years respectively. The last of these may possibly be driven by Jupiter’s orbit around the Sun, although the connection is obscure, but the first two are even more mysterious.

One thing that became clear is temperature rises in a certain band are often matched by falls at the same latitude in the opposite temperature – as if there really were seasons, but without matching changes in neighboring bands. The pattern is particularly strong at 16°, 22°, and 30° from the equator.

“That was the most surprising of all,” Orton said in a statement. “We found a connection between how the temperatures varied at very distant latitudes. It’s similar to a phenomenon we see on Earth, where weather and climate patterns in one region can have a noticeable influence on weather elsewhere, with the patterns of variability seemingly ‘teleconnected’ across vast distances through the atmosphere.”

There is also an anticorrelation between temperatures in the equatorial troposphere and in the stratosphere 60-70 kilometers (37-43 miles) above. This resembles vertical temperature waves seen in Saturn’s atmosphere, and may prove easier to explain.

Studying the atmosphere of Venus alerted meteorologists to the consequences of a run-away Greenhouse effect. Likewise, comparisons with Mars proved helpful in exploring our own planet’s atmosphere. Now perhaps it is Jupiter’s turn.

With a year that lasts 11.9 Earth years, it takes a long time to find the patterns in Jupiter’s cycles, so it’s not surprising no one has taken the next step of explaining them. Nevertheless, co-author Leigh Fletcher of the University of Leicester is optimistic: “We’ve solved one part of the puzzle now, which is that the atmosphere shows these natural cycles,” Fletcher said. “To understand what’s driving these patterns…we need to explore both above and below the cloudy layers.”

The paper is open access at Nature Astronomy.

Source Link: Forty-Year Study Reveals Cycles In Jupiter’s Atmospheric Temperatures We Can’t Yet Explain