Worldwide, more than forty percent of amphibian species are considered endangered, and Dr Marissa Parrott of Zoos Victoria told IFLScience that’s probably an underestimate, as the ones we haven’t studied are more likely to be in trouble. Rather than feeling helpless however, Parrott has just collected and frozen sperm that will preserve the genetic diversity that three of Australia’s critically endangered frog species need to survive.

For decades a few scientists, and many more people without qualifications, have proposed saving endangered species by storing their DNA in a sort of frozen ark. A much larger group of scientists have pointed out why the idea is unlikely to work: once a species is gone there are immense obstacles to bringing it back.

However, that doesn’t mean there’s no role for deep freezing in biological preservation. One of the keys to keeping species alive is maintaining genetic diversity, which provides adaptability in the face of threats like climate change and novel diseases. When populations get small enough, they often lack the diversity they need to recover.

To address this problem, Dr Aimee Silla of the University of Wollongong has developed protocols to freeze frog sperm to -196°C (-321°F) and rewarm it while keeping it viable, a process that only works if done at just the right speed.

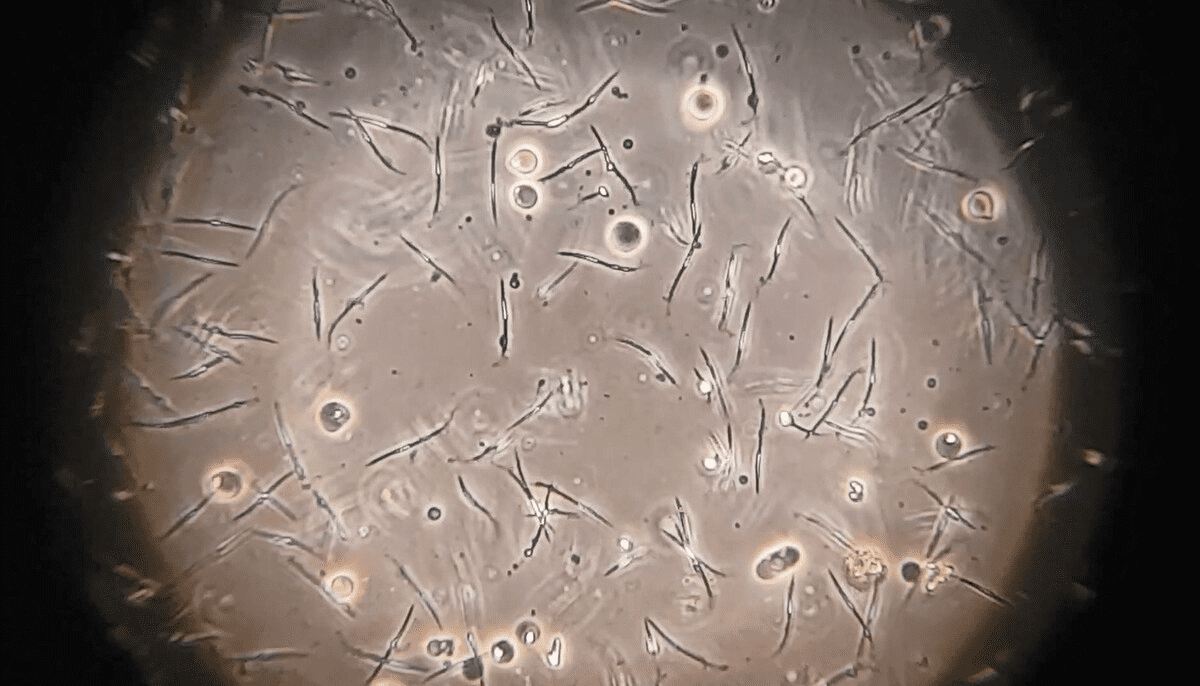

Frog sperm frozen to -196°C will last for decades. Image credit: Zoos Victoria

“The ultimate aim is to have sustainable populations back in the wild,” Silla said in a statement emailed to IFLScience. “If we can use these technologies to improve the genetic management of populations, and to improve the number, health and viability of offspring that we are producing in captivity and that we are releasing in the wild, then that is our best opportunity to save these species from extinction.”

Parrott has been applying Silla’s process to Australia’s rarest amphibian, the Baw Baw frog, as well as the critically endangered Spotted Tree Frog and the Stuttering Barred Frog, which almost counts as privileged by amphibian standards, being merely endangered.

Freezing sperm requires collecting it first. Fortunately, Parrott told IFLScience, that’s not particularly hard for frogs, who apparently don’t guard their jizz all that jealously. “We just give them a hormone injection and they let out their sperm in their urine, which we call spermic urine,” she told IFLScience. “Every two hours we use a tiny glass catheter to collect it. They’re delightful animals to work with.”

This is the face of a Stuttering Barred Frog who realizes his sperm has been stolen and he still isn’t going to get to be a prince. Image Credit: Zoos Victoria

The sperm is separated from the urine and analyzed for quality and quantity before storing in a biosecure facility. Decades after the donor frog has died its sperm will still be able to a-wooing go.

Since frogs’ eggs are fertilized externally, when the time comes to apply the sperm it will be a much easier process than for a mammal or bird. So long as programs – such as the one run by Zoos Victoria to preserve seven frog species, these three included – can keep some females alive and laying, the sperm will be able to increase biological diversity. This in turn will maximize the prospect that some of the tadpoles will be suited to the circumstances a changing world will throw at them, allowing them to keep playing their essential ecosystem role in insect control.

Parrott told IFLScience the main threats to frogs in general are climate change, habitat destruction, and the chytrid fungus. However, in the case of the Spotted Tree Frog, there are additional hazards in introduced fish species and pollution from bushfires washing into the streams in which they live.

Source Link: Frozen Frog Sperm Is A Defense Against The Amphibian Apocalypse