There are few things more sinister than a parasite that hijacks the brains of infected ants and effectively turns them into zombies. But new research has shown that these tiny worms are even more sophisticated than we gave them credit for, altering the behavior of their unwitting hosts in response to temperature to maximize their chances of survival.

A parasite’s goal is to exploit other species so that it can progress its own life cycle by any means necessary. Some of our most feared human diseases, like malaria and sleeping sickness, are caused by parasites, but many other animals and plants have parasitic pests to contend with too.

The lancet liver fluke (Dicrocoelium dendriticum) is a flatworm with a complex, multistage life cycle. For part of this cycle, the fluke sets up camp in the bodies and brains of ants, temporarily turning them into “zombies”. You might have heard of the so-called zombie fungus, Cordyceps, which infects ants and bends them to its will; this is a bit like that, except with fewer mushrooms exploding out of the tops of heads.

The cycle starts when an ant unwittingly consumes a lovely ball of snail mucus that contains fluke larvae. This can lead to an infection with several hundred parasites, but only one breaks away from the pack and heads for the ant’s brain. The rest hide out in its abdomen.

“Here, there can be hundreds of liver flukes waiting for the ant to get them into their next host,” said Brian Lund Fredensborg, coauthor of the new study into these troublesome critters, in a statement. “They are wrapped in a capsule which protects them from the consequent host’s stomach acid, while the liver fluke that took control of the ant, dies. You could say that it sacrifices itself for the others.”

Researchers have already observed the changes in ant behavior induced by the fluke once it reaches the brain. The next stage of the parasite’s life cycle requires it to be eaten by a grazing animal, such as a cow or sheep. To maximize the chances of that happening, the fluke causes infected ants to climb to the top of blades of grass, holding themselves steady with their powerful jaws until a grazer comes along.

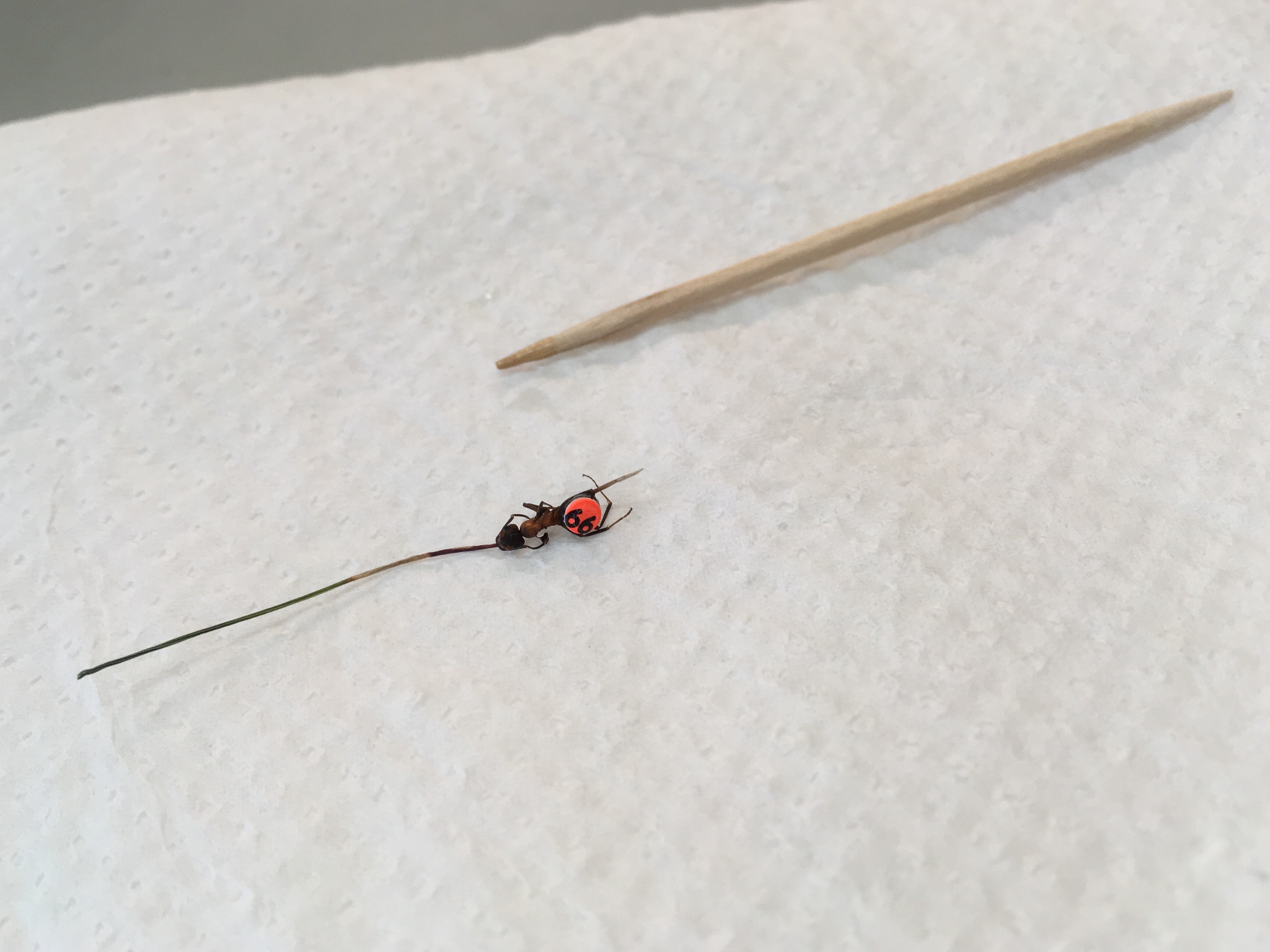

To study this in more detail, the researchers painstakingly tagged hundreds of ants from the Bidstrup Forests of Denmark with number and color markers. They could then keep track of them and assess whether the parasite’s effect on the ants changed in response to things like daylight levels, humidity, and temperature. One of these factors stood out almost immediately.

“It took some dexterity to glue colors and numbers onto the rear segments of the ants, but it allowed us to keep track of them for longer periods of time,” said Fredensborg.

Image credit: University of Copenhagen

“We found a clear correlation between temperature and ant behavior. We joked about having found the ants’ zombie switch,” Fredensborg said.

It’s in the parasite’s best interest to have the ants positioned at the top of the grass blades during the morning and evening hours when the grazers come along to feed. But in the middle of the day, when the sun’s rays become too strong, the researchers have now discovered that the parasite makes the ants climb back down to seek shelter.

“Getting the ants high up in the grass for when cattle or deer graze during the cool morning and evening hours, and then down again to avoid the sun’s deadly rays, is quite smart,” said Fredensborg. “Our discovery reveals a parasite that is more sophisticated than we originally believed it to be.”

The parasite’s life cycle continues – once the flukes are released as the ant is digested in the new host’s stomach, they undergo sexual reproduction and the eggs are eventually excreted. The eggs are eaten by snails, in which the parasites undergo asexual reproduction until they are expelled in a ball of mucus, and the whole cycle starts again.

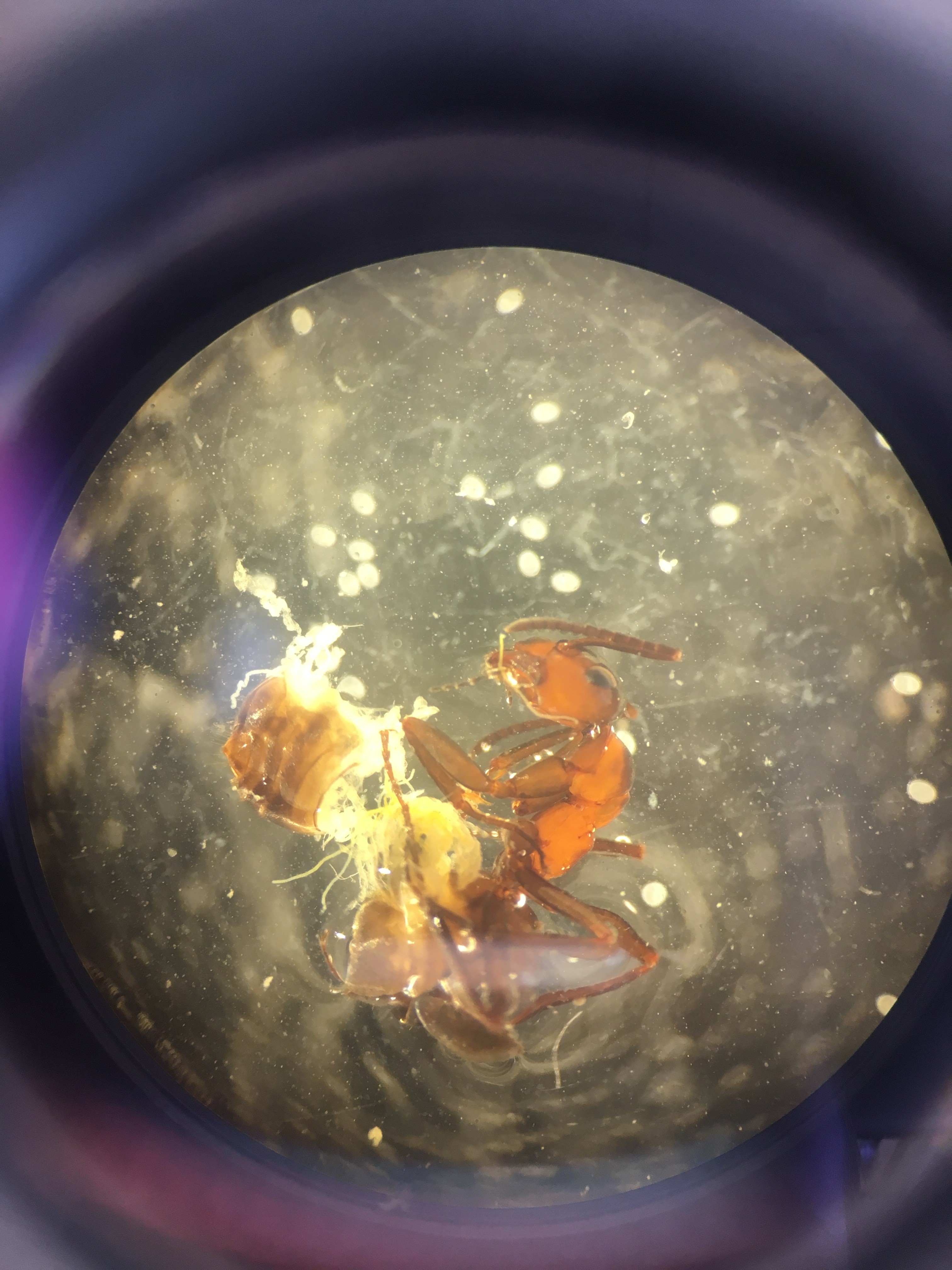

The white encapsulated parasites are clearly visible spilling out of the abdomen of this dissected ant.

Image credit: Brian Lund Fredensborg

There are still questions left to be answered about exactly how the fluke is able to take control of the ant’s brain, but Fredensborg highlighted how these kinds of host-parasite interactions could be more central to our ecosystems than many believe.

“Historically, parasites have never really been focused on that much, despite there being scientific sources which say that parasitism is the most widespread life form. […] the hidden world of parasites forms a significant part of biodiversity, and by changing the host’s behavior, they can help determine who eats what in nature.”

The study is published in the journal Behavioral Ecology.

Source Link: How A Brain Parasite Turns Ants Into "Zombies" That Hide From The Sunlight