Whether you’re a fan of amorphous solids or just enjoy being able to see stuff outside, glass is a pretty cool material. But how does it work on an atomic level? Why can we see through it, when we can’t see through (for instance) metals, Danny DeVito, and pasta? And what actually is glass anyway?

Is glass a liquid or a solid?

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

There’s an often repeated “fact” that glass is in fact a liquid, but it moves too slowly for us to see. Usually accompanied by this “fact” is the idea that stained glass windows in old churches and cathedrals are thicker at the bottom, the result of gravity pooling the glass at the bottom over the course of centuries. This isn’t really the case. In fact, glass has a lot in common with liquids, but things in common with solids too.

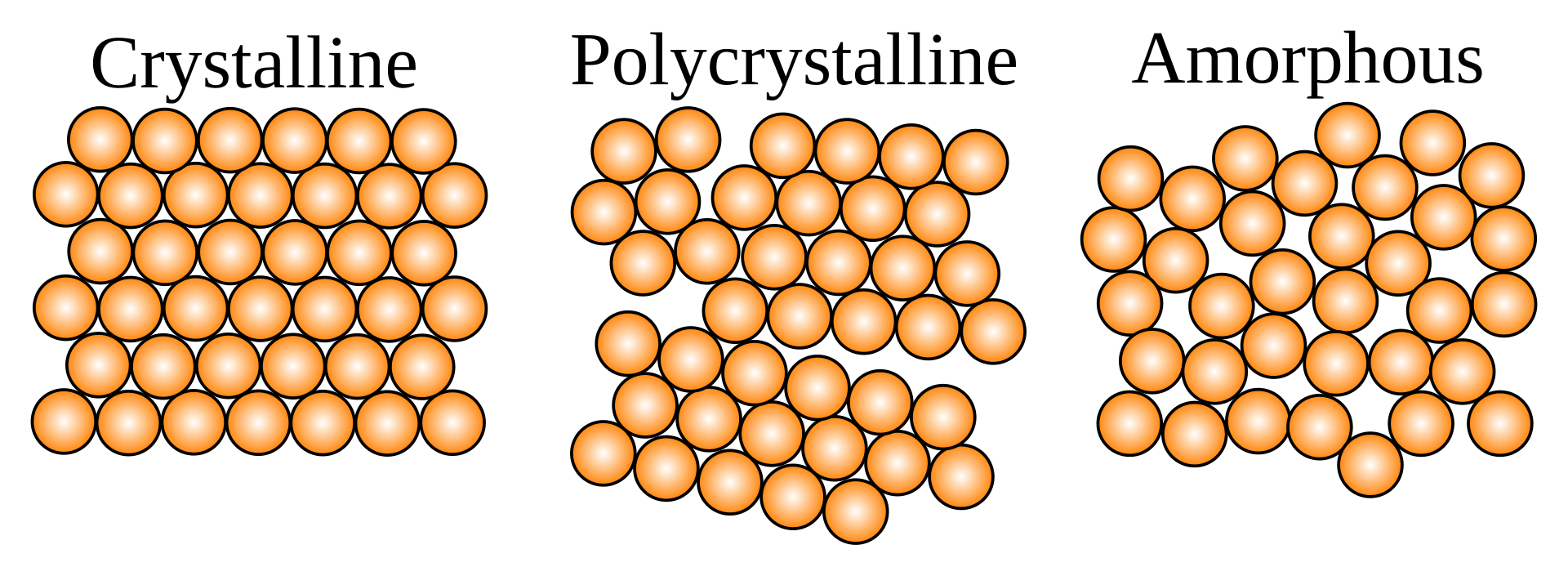

There are a lot of glasses out there, but it’s probably easiest to focus on silicon dioxide, the main ingredient in most glass. When you heat up quartz sand (SiO2) enough it melts into a liquid. In the liquid state, individual molecules are free to flow around within the material. But if you cool it quick enough, unlike in metals and other solids, it does not form organized crystalline structures, nor polycrystalline structures made of smaller crystalline structures packed in together.

“As a liquid is cooled, its viscosity normally increases; but increasing viscosity has a tendency to prevent crystallisation. Usually when a liquid is cooled to below its freezing point, crystals form and it solidifies; but sometimes it can become supercooled, remaining liquid below its melting point because no nucleation sites exist that can initiate the crystallisation,” Philip Gibbs explains for the University of California, Riverside.

“If the viscosity rises enough as it is cooled further, it might never crystallise. The viscosity rises rapidly and continuously, forming a thick syrup and eventually an amorphous solid. The molecules then have a disordered arrangement, but sufficient cohesion to maintain some rigidity.”

Glass is amorphous.

In this state, glass has properties similar to a liquid and a solid, but does not flow like a liquid as stated by the oft-repeated factoid.

“On short timescales, glass behaves much like a solid. But the liquidlike structure of glass means that over a long enough period of time, glass undergoes a process called relaxation,” materials scientists John Mauro and Katelyn Kirchner explain in a piece for The Conversation.

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

“Relaxation is a continuous but extremely slow process where the atoms in a piece of glass will slowly rearrange themselves into a more stable structure. Over 1 billion years, a typical piece of glass will change shape by less than 1 nanometer – about 1/70,000 the diameter of human hair.”

This amorphous, chaotic structure allows light to pass through it without much scattering taking place, like how light can pass through water. But it doesn’t really explain why glass is transparent. For this, you need to get electrons involved.

Why can we see through glass?

When a photon of light hits a solid material, there are a few things that can happen at the subatomic level. The photon can be absorbed by the material, usually heating it up with that photon’s energy. In this case, the photon effectively disappears, meaning there is no reflection, nor does light emerge from the other side of the material as it does in glass and other transparent solids.

The photon can also be reflected. This is where (very generally speaking, as electromagnetism is, famously, quite complex) the photon is momentarily absorbed, and then a photon of the same wavelength is emitted.

ADVERTISEMENT GO AD FREE

In both these cases, thanks to absorption, light does not make it through the object. However, light can make it through certain materials unchanged, which is known as transmission. If the incoming photon is not high enough energy to excite electrons to a higher energy state, the photon is not absorbed, but is instead allowed to pass through.

In most materials, visible light is enough to excite electrons into their higher energy states, and so they are not translucent. But in glass, the gaps between possible energy states are large enough that visible light does not kick the electrons to their higher energy level.

While glass lets visible light through, ultraviolet light is enough to excite electrons into higher energy states, and so many of these wavelengths of light do not make it through, which is what gives glass some UV ray-filtering properties.

Source Link: Is Glass Really A Liquid? And How Come We Can See Through It?