When I get up to stand, it doesn’t occur to me to question how I can move because, well, we’ve figured it out. But there was a time when the way our tissues and nerves produced movement was a complete mystery.

Turns out, the quest to figure such a simple thing out inspired one of the greatest gothic science fiction stories of all time: Frankenstein. Ahead of the Netflix release from director Guillermo del Toro, let’s take a look at the real science that inspired its original creator, Mary Shelley.

Luigi Galvani and “animal electricity”

Our story begins with Luigi Galvani, an Italian physician who, in the 1780s, began doing some rather eye-opening experiments with frogs. Like many scientific origin stories, what happened next exists in several versions (we like the soup story, too), but according to historians at the University of Münster, it began with a table full of frogs used for medical training.

Frogs were often used in medical training for dissections, but one day something interesting happened when one of Galvani’s assistants touched a frog’s leg with a scalpel. Another student in the room reported seeing a spark just as the scalpel reached the frog and so began Galvani’s search for “animal electricity” – a force he believed could explain how muscles move.

Frankenstein’s frogs

To test the theory, he got some more frogs. Well, half frogs, I should say. The poor amphibians were relieved of their upper bodies so that only the legs and nerves were left behind.

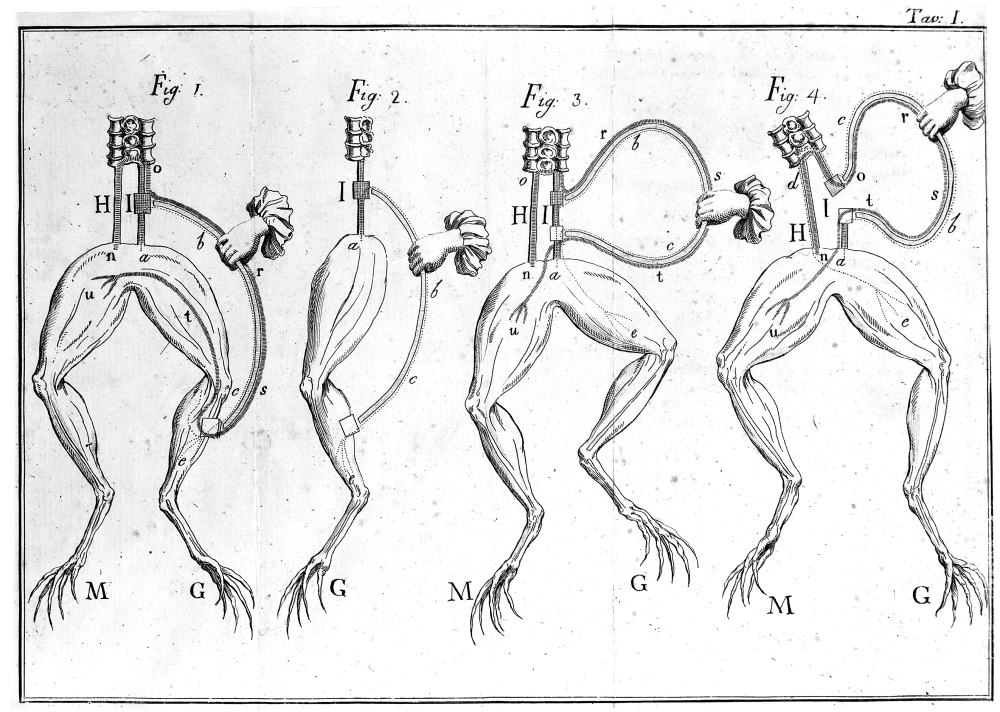

An illustration of how the frogs were prepared for Galvani’s experiments.

He then hung them from metal hooks on the iron railing of his terrace, hoping lightning might strike and set them twitching. It sounds like some pretty grim Halloween decorations, but during thunderstorms, the legs really did move.

Eventually Galvani proved that it was possible to produce the effect without lightning by connecting the nerves with two different metals that formed an electrical circuit. His theory of Galvanism was born in 1786, a breakthrough that captured the imagination of a young Mary Shelley as she penned her 1818 novel, Frankenstein.

A galvanised corpse

A great achievement for Galvani, it could be said, and if only it had stopped there. His nephew, Giovanni Aldini, decided to carry on his uncle’s legacy, and it’s here that things start to get really weird. As Dr Austin Lim writes in his book Horror On The Brain: The Neuroscience Behind Science Fiction, Aldini began testing on things much bigger than frogs.

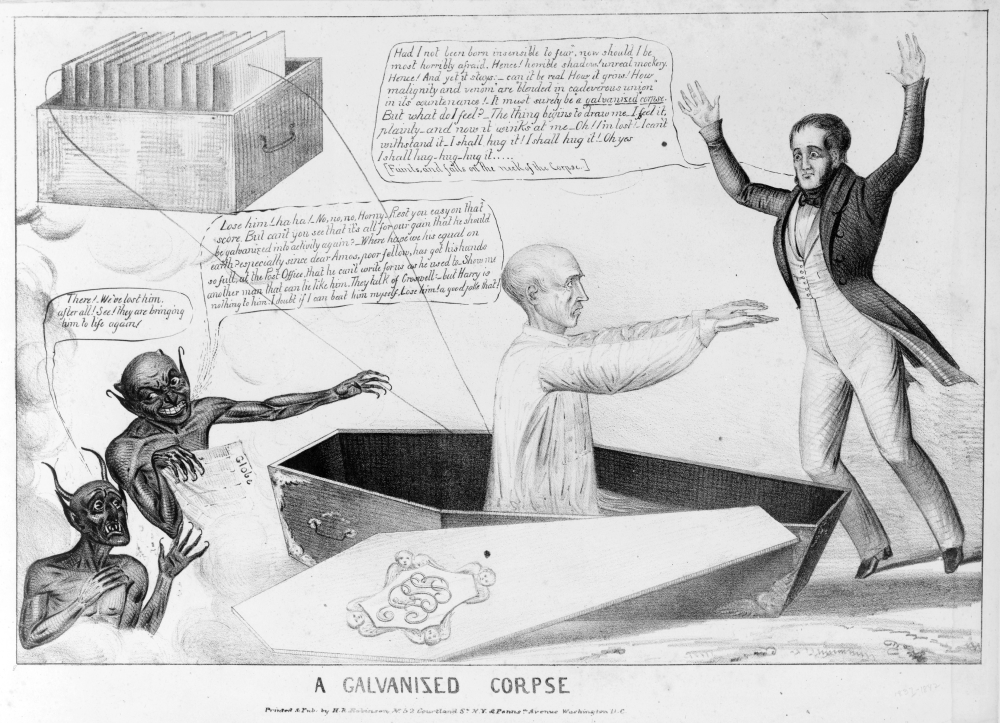

A galvanised corpse.

Stepping out of the lab, he brought galvanism to the public in demonstrating how decapitated oxen, sheep, horses, and dogs could all be zapped into gnashing, blinking, and thrashing with a bit of electricity. Then, he took the show to the gallows.

An account of Aldini’s human experiments was shared by Professor of History at Abertyswyth University Iwan Morus in an article published to The Conversation. It reads:

“On the first application of the process to the face, the jaw of the deceased criminal began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process, the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.”

Hoo boy. By comparison, Guillermo del Toro’s interpretation for Netflix will be light relief.

Source Link: “It’s Alive!”: The Real (And Horrifying) Science That Inspired Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein