The JWST has turned its attention to Saturn, and captured images of a season we’ve never observed there before: the end of the northern hemisphere’s summer. This means the space telescope is able to see what has been one of the highlights of the ringed planet in recent years, the enormous polar vortex, for what may be the last time.

Saturn takes almost thirty years to orbit the Sun, which means each season lasts more than seven years. With an axial tilt of almost 27 degrees, there’s even greater variation in sunlight, proportionally speaking, between summer and winter than on Earth.

The Voyager spacecraft passed Saturn during the northern hemisphere’s spring. By the time Cassini arrived there 24 years later, we were almost back there again. The spacecraft watched the planet for almost half a year – but now, however, the JWST offers the chance to watch seasons we haven’t seen before, at least when watching Saturn makes it to the top of its long priority list.

If the two hemispheres are identical, there might not be much new to learn from the mirror image of what Cassini saw, but it’s not clear if they are.

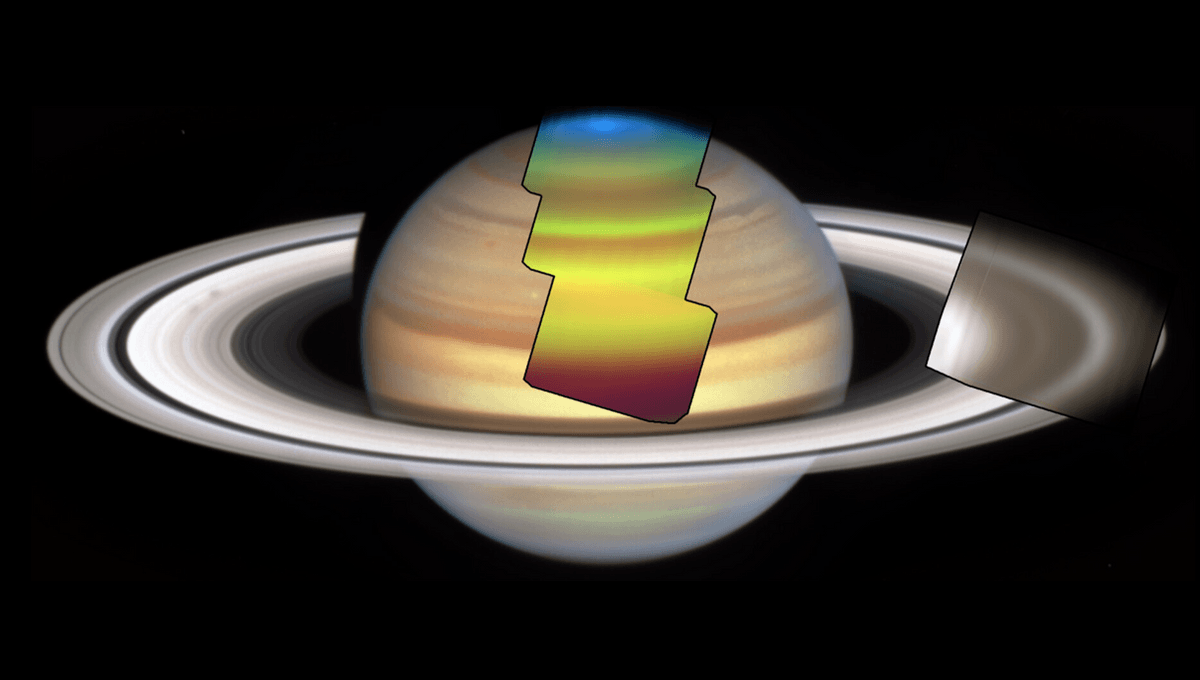

The outstanding feature of the northern spring and summer has been an enormous vortex of warm gases at the north pole that Cassini first witnessed in 2010. Known as the north-polar stratospheric vortex, this immense phenomenon surrounds what is called the north polar cyclone, which is 1,500 kilometers (900 miles) wide on its own. A counterpart has yet to show up in the south, although it’s not clear why a gas giant would be asymmetric.

During the summer, these areas get warmed sufficiently to cause hydrocarbons to rise through Saturn’s atmosphere. The vortex is possibly the largest ongoing storm we have witnessed, once exceeding Jupiter’s Great Red Spot in extent. Cassini witnessed the release of a hundred times more ethylene from the northern vortex than planetary scientists thought possible beforehand.

As Saturn heads towards its 2025 equinox, the vortex is expected to fade, and the JWST has already seen the start of this process.

Professor Leigh Fletcher of the University of Leicester is leading a team that, in November 2022, saw the hydrocarbons have almost vanished from lower northern latitudes as stratospheric circulation changed direction and temperatures fell.

To do this, Fletcher’s team had to deal with some unusual problems for astronomers, including observing an object too large and bright for their telescope. The measurements were made with the JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), which has such a small field of view it can’t see the whole planet at once. Moreover, the detectors are close to being saturated by the infrared light Saturn reflects. The moons present no such problems, but have to compete with scattered light from the planet and rings.

“We started designing these Saturn observations more than 8 years ago, so when that first data landed in late 2022, it was certainly a career highlight,” Fletcher said in a statement.

As well as hydrocarbons, the team tracked concentrations of phosphine, ammonia, and water in Saturn’s atmosphere. The first two are currently enriched at the equator which the team says indicates; “Strong mixing from the deeper troposphere.”

“JWST can see in wavelengths of light that were inaccessible to any previous spacecraft, producing an exquisite dataset that whets the appetite for the years to come,” Fletcher said. “This work on Saturn is just the first of a program of observations of all four giant planets, and JWST is providing a capability beyond anything we’ve had in the past – if we can get so many new findings from a single observation of a single world, imagine what discoveries await?”

The results of the observations are published open access in the journal JGR: Planets.

Source Link: JWST Observes Saturn’s Northern Polar Vortex Before It Fades With Summer’s End