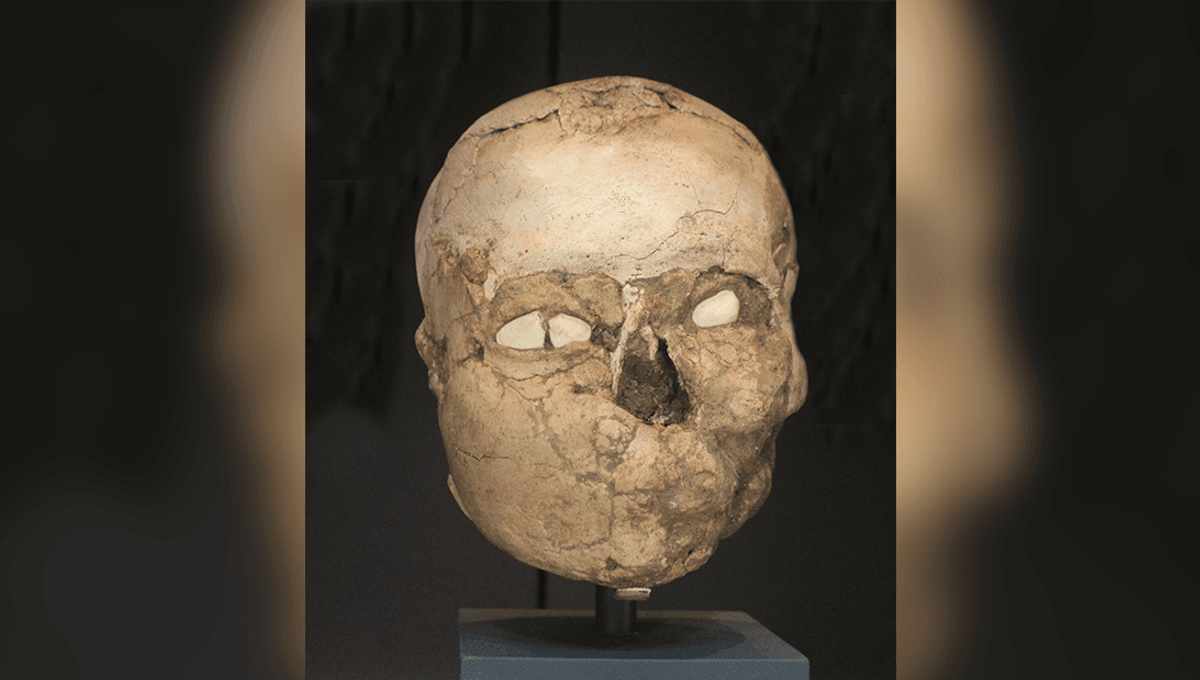

Around 9,000 years ago, during what’s known as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, the ancient inhabitants of the Middle East developed the curious custom of plastering the skulls of their dead. Often, these coated crania were then decorated with colorful pigments and other adornments to make them appear more lifelike, although historians are unsure exactly why and how this odd practice came about.

The first Neolithic plastered skulls were discovered in the Palestinian city of Jericho in 1953 by archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon. Covered in colorful plastered masks, these remains also had shells placed into the eye sockets, supposedly in an attempt to recreate the eyes of the skulls’ original owners.

Similar examples have since been found at sites from roughly the same period across the Levant and Anatolia, although interpretations of this striking funerary practice vary. The most popular explanation is that skulls were given plaster masks in order to restore them to life, and that the objects were then worshiped as ancestor figures.

Delving into the many mysteries surrounding these ancient noggins, researchers have now conducted detailed analyses on seven plastered skulls found at the archaeological site of Tepecik-Çiftlik in Turkey. Presenting their findings in a new study, the authors explain that the crania belong to six young adults and one child, suggesting that youthful individuals may have been specifically chosen for this interesting tradition.

As with other plastered skulls, these remains were coated in a material that had been dyed using an array of pigments. Identifying coloring agents including azurite and goethite, the study authors note the presence of red and blue hues in the plaster masks.

“Selected pigments were used to create a more dramatic appearance,” write the researchers. Despite the Tepecik-Çiftlik skulls lacking embellishments such as seashells for eyes, the authors insist that these findings are consistent with other examples and “correspond to a common ‘craftsmanship’ that was probably transmitted through a common oral culture.”

Perhaps most interestingly of all, the researchers also discovered that the plastered skulls were several hundred years older than the graves in which they were buried, indicating that they had been used for quite some time before finally being interred. “These results can be taken as indicative of a clue to the long-term community use of plastered skulls and crania,” write the authors.

During their extended period of employment, the plastered skulls likely required several rounds of touch-ups and renovations. Evidence for this can be seen in some of the Tepecik-Çiftlik skulls, which sport noses that appear to have been fashioned after the main mask had been completed.

Other findings, including cut marks on the bones themselves, “provide concrete evidence that soft tissues of the skulls of selected individuals were removed before the plastering process began.”

However, despite providing some intriguing insights into the history of these incredible artifacts, the study authors are ultimately unable to reveal why the skulls were plastered or how they were used.

The study is published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Source Link: Neolithic "Plastered Skulls" Found Across The Middle East And We Don't Know Why