There is far more variation in the way the brains of pessimists operate from each other than those of optimists, a new study finds. In other words, those who see life through a positive lens tend to use the same rose-colored glasses, whereas pessimists are more original and creative in their negative outlook. The findings could be helpful for those wanting to learn how to become more optimistic, while potentially also providing another reason why pessimism survives, despite its evolutionary drawbacks.

Even people who have never read Tolstoy are often familiar with his famous opening line to Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The quote is so well known because it resonates with people’s experience, and psychologists have investigated if it might apply to the individual as well as the collective.

A team led by Dr Yanagisawa Kuniaki of Kobe University combined approaches used in psychology and neuroscience by challenging 87 married people to imagine specific future events happening to them or their partner while lying in an fMRI machine. The sample group was deliberately chosen to include people with a mix of future expectations.

The fMRI machines revealed the neurons activated in the exercise, and showed that the images of different optimists’ medial prefrontal cortexes were remarkably similar. “What was most dramatic about this study is that the abstract notion of ‘thinking alike’ was literally made visible in the form of patterns of brain activity,” Yanagisawa said in a statement. Meanwhile, pessimists’ brains produced different maps from each other when given the same prompt.

However, if pessimists reading this are feeling smug about their originality compared to the blandness of the optimists, the project revealed something that might give them pause. An individual optimist’s brain looks quite different when contemplating a positive or negative event, as one might expect. That’s less true for pessimists.

“This means that more optimistic people perceive a clear distinction between good and bad futures in their brains. In other words, optimism does not involve positive reinterpretation of negative events. Instead, optimistic individuals typically process negative scenarios in a more abstract and psychologically distant manner, thus mitigating the emotional impact of such scenarios,” Yanagisawa said.

In a world where many of us are at risk of doom-spiraling, that abstraction of negative outcomes could be a handy skill to learn.

“By contrast, when envisioning positive events, optimistic individuals imagine them vividly and concretely, thus reinforcing the emotional significance and clarity of these scenarios,” the authors report.

“The everyday feeling of ‘being on the same wavelength’ is not just a metaphor. The brains of optimists may in a very physical sense share a common concept of the future. But this raises new questions. Is this shared mechanism something they are born with or is it woven in later, for example through experience and dialogue?” Yangisawa pondered. “I believe that elucidating the process by which this shared reality emerges is a step towards a society where people can communicate better.”

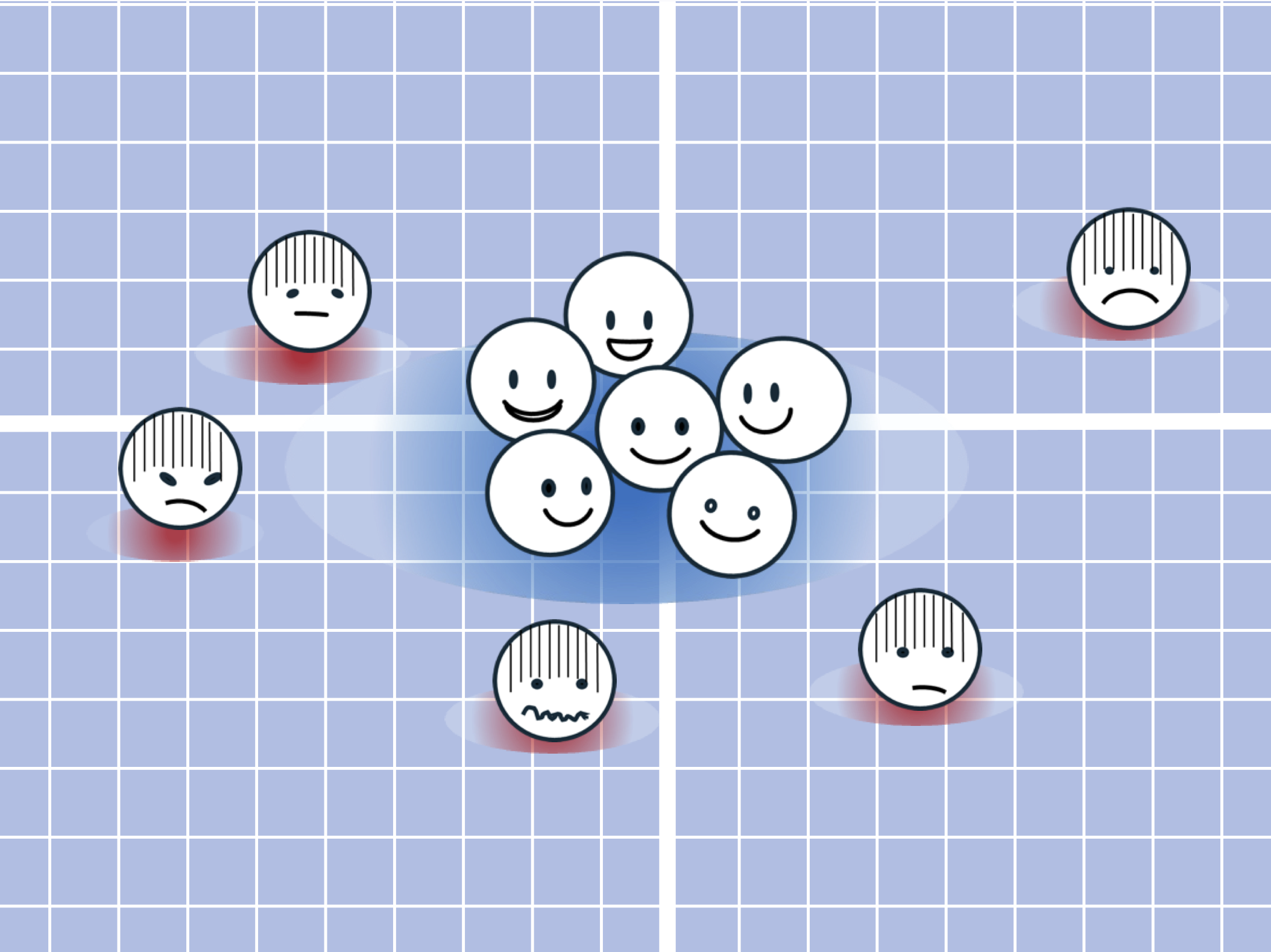

Visual representation of the way optimists’ brains align, while pessimists differ in how they expect things to go wrong.

Image credit: ASANO Kohei, SUGIURA Hitomi

Any mindset can be damaging when taken to extreme, but many past studies have revealed benefits to optimism such as better health and lower early mortality. Society also tends to reward optimism – no one likes a downer, as Cassandra could tell you, if you’d listen. The stigma towards pessimists is so widespread the authors even avoided the word when summarizing the findings: “optimistic individuals are all alike, but each less optimistic individual imagines the future in their own way.”

The benefits of optimism have always posed an evolutionary puzzle – why do pessimists still exist when it’s a hazard to health?

One possible explanation is that humans are social animals, and that a tribe will do best with a mix of characteristics. Any ancient human population composed entirely of optimists probably died crossing rivers because they convinced themselves there would be no crocodiles or starved because they didn’t prepare for bad seasons. This work also hints at the possibility that the individuality that comes with pessimism lends itself to more diverse approaches to problems, with a greater chance that one will succeed than the optimists who all try the same thing.

The authors acknowledge that, while their results were statistically significant for people imagining scenarios affecting themselves, significance was not achieved when comparing brain maps of those imagining events affecting their partners. However, they attribute this to “methodological constraints” they think can be addressed in future, rather than thinking patterns being different for how we imagine our own futures and those of our loved ones.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source Link: Optimists' Brains Work The Same Way, While Pessimists Dream Up Their Own Disasters