It’s surprisingly easy to learn to operate an extra limb, a new study has found, despite the fact humans haven’t had to do it for millions of years, since some ancestral species lost their tails. Admittedly, the study demonstrated the capacity to repurpose leg muscles, rather than operate a true additional limb, but it could still open the door to better surgical outcomes.

People with damaged or amputated arms or legs can learn to operate prosthetic limbs quite quickly, but this just requires reorientating brain circuits that have been with us since time immemorial. We also get the hang of tools quickly, but given what we are learning about tool-making in other primates that’s also probably an application of something our ancestors mastered a very long time ago.

On the other hand, throughout our evolution we have only had one other hand, so the idea of operating our own limbs, and some extra robot ones as well, is very new territory. Whatever brain circuits squid and octopuses developed to keep everything working harmoniously came along long after our last common ancestor.

Consequently, when an Anglo-Australian collaboration gave people additional limbs they can control at the same time as their hands it was reasonable to expect things wouldn’t go so well. Surprisingly, however, the subjects caught on very fast.

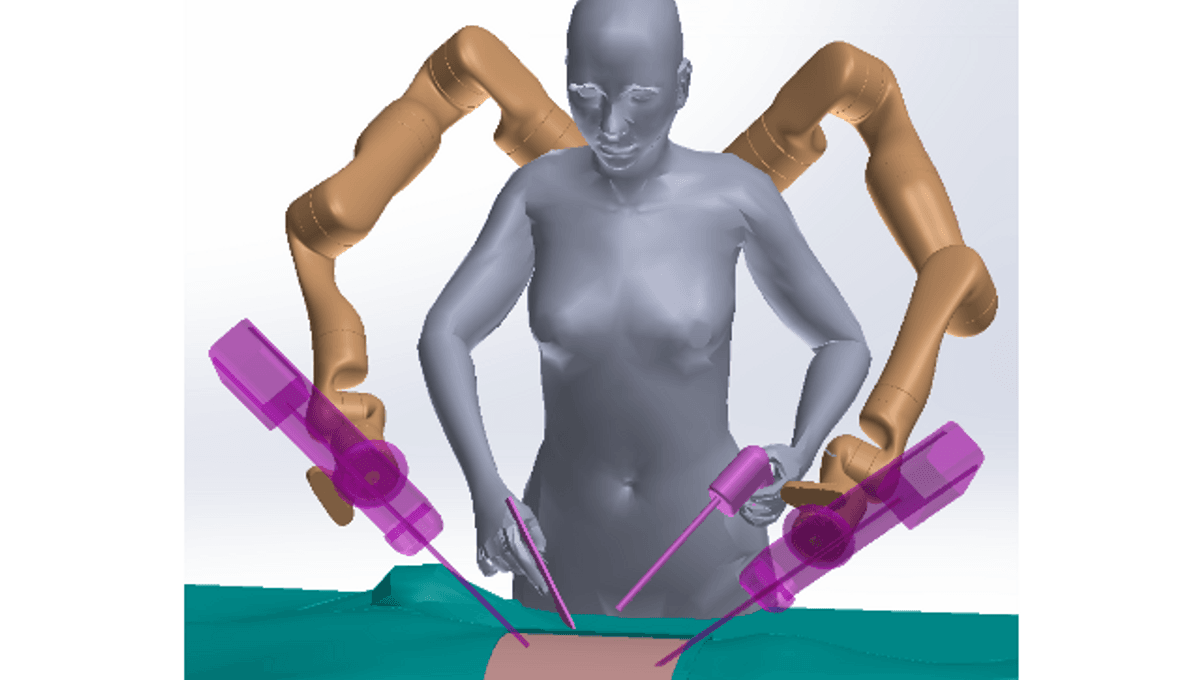

“Many tasks in daily life, such as opening a door while carrying a big package, require more than two hands,” said Dr Ekaterina Ivanova of Queen Mary University in a statement. “Supernumerary robotic arms have been proposed as a way to allow people to do these tasks more easily, but until now, it was not clear how easy they would be to use.”

Giving people an actual mind-controlled robot arm would be a bit pricey for the moment. Instead Ivanova and colleagues had subjects play a computer game that required the operation of three effectors to move the center of mass of a triangle within three seconds.

Two of the effectors were operated through hand controls, while the third used a foot control. Some were given four 15-minute training sessions in its use; the others had to collaborate with a partner who operated the third effector instead. To make things fair, the partner also controlled the third effector with their foot; the mental strain of operating all three at once was avoided, but feet did not have to compete with hands at fine motion control.

A previous study using a similar challenge found working with a partner produced better outcomes than trying to control all three virtual limbs at once. However, in that case those operating on their own had been thrown in without training.

This time the two groups performed equally well, indicating that an hour was all it took to learn to use the virtual third arm effectively. Ivanova and colleagues note how impressive this is. “When a pair performs a task they are able to draw upon a lifetime of interactions working with other people,” they write. Three-armed performance is far newer.

“Our findings are promising for the development of supernumerary robotic arms,” Ivanova said. “They suggest that these arms could be used to help people with a variety of tasks, such as surgery, industrial work, or rehabilitation.”

The study is published open access in the IEEE Open Journal of Engineering.

Source Link: People Learn To Control A Robotic Third Arm Surprisingly Quickly