Finding detailed fossils of soft-bodied organisms is exceptionally rare, making each discovery a unique opportunity to fill in gaps in both the fossil record and our understanding of evolution. That’s why the 1982 description of Proteroctopus ribeti – a 165-million-year-old fossil cephalopod – was such a big day for octopus science. Over the decades that followed, this Jurassic-era creature has revealed surprising details about the evolutionary journey of octopuses, from their more squid-like relatives to the intelligent aliens we see today.

ADVERTISEMENT

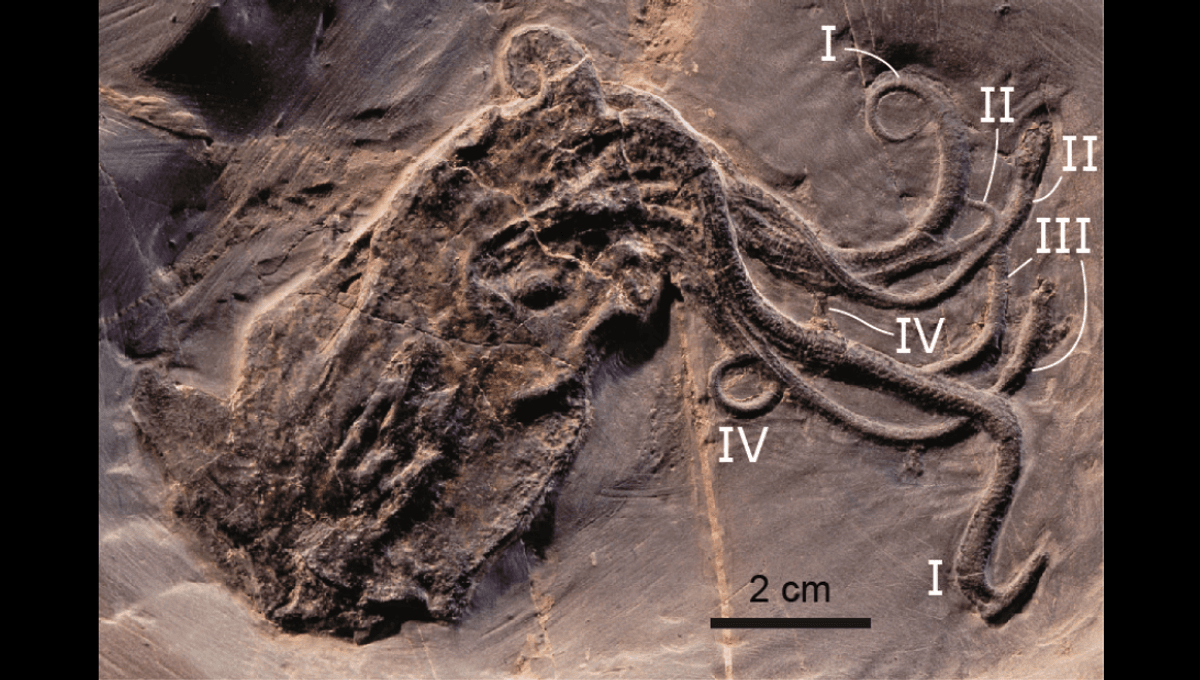

The fossil was discovered in what we now know as France, at the La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte. The site is famous for unearthing exceptionally well-preserved and biodiverse fossils. Proteroctopus is now housed at the Musée de Paléontologie de La Voulte-sur-Rhône, where you can see with the naked eye its flexible arms and much of its soft body.

Scanning Proteroctopus

In 2016, a team of scientists decided to take a closer look using synchrotron X-ray microtomography, exposing its internal and external structures in unprecedented detail. When Proteroctopus was first described, it was thought to be an early octopus. However, the 2016 study repositioned it as a basal member of Vampyropoda, the group that includes both vampire squids and octopuses.

One of the most surprising findings was that Proteroctopus had two rows of suckers on its arms. Previously, scientists believed this trait evolved later in the group’s evolution, but Proteroctopus suggests it was actually an ancestral feature.

Another unexpected discovery was its lack of an ink sac. Given that modern octopuses – and many Jurassic-era cephalopods – have ink sacs, this was surprising. However, what it lacked in ink it may have made up for in steering power, with two small but well-developed fins that could’ve made it a better swimmer than octopuses alive today (though we do see these kinds of fins in deep-sea cirrate octopuses).

A key transitional form

The scans also showed that Proteroctopus had a poorly mineralized gladius, a kind of internal shell that we don’t see in modern octopuses. This suggests early octopus relatives weren’t as soft-bodied as we thought, and Proteroctopus appears to be a key transitional form between squid-like ancestors and modern octopuses.

Another striking discovery was the axial nerve running through each arm. This feature is seen in the incredibly complex nervous systems of modern octopuses’ arms, and represents an early step towards that complexity.

Octopus fossils – why so rare?

Proteroctopus is one of the oldest and best-preserved fossil cephalopods, but it is not the oldest octopus fossil ever found. There’s also Pohlsepia mazonensis that dates back ~296 million years to the Carboniferous, and was retrieved from Mazon Creek Lagerstätte. It’s thought it may represent an even earlier octopod relative, though its classification remains uncertain. Then we have Vampyronassa rhodanica, also 165 million years old from the Jurassic and found at the same fossil site as Proteroctopus.

Despite not being the oldest, Proteroctopus remains one of the most significant, as it provided pivotal information as to how ancient cephalopods evolved. For all the examples we have, fossil octopuses remain rare as fossilization favors animals with tougher tissues. However, a study into frog fossilization unearthed how one key factor can significantly alter how much detail is preserved in soft-bodied animals.

Source Link: Scanning A 165-Million-Year-Old Octopus Fossil Revealed Surprising Features In Proteroctopus