Researchers have gained new insights into the Maya calendar and, in particular, the ability to predict eclipses. Like other advanced ancient civilizations, the Maya looked at the sky for auspicious signs and divine punishment, but their calendar is quite different from what we are used to, making its use an enduring mystery to modern archaeologists.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content.

The Maya astrological calendar had 260 days, and it was used to divine individuals’ destinies. In the Dresden Codex, there is a table with 405 new Moons, which amounts almost exactly to 46 of these 260-day cycles, so they could predict the occurrence of the full Moon or new Moon to within one day.

Eclipses happen either at full Moon (lunar eclipses) or at the new Moon (solar eclipses), but only when the Earth, the Moon, and the Sun are at their nodes. The orbit of the Moon around the Earth is slanted with respect to the orbit of the Earth around the Sun; only near the nodes are the three bodies are roughly on the same line, and an eclipse can happen.

There were two spots in the table that were closest to the exact alignment of the Earth, Moon, and Sun.

Professor John Justeson

The 260-day calendar not only allowed for the prediction of Moon phases, but also for the prediction of eclipses that might have happened anywhere in the world. While lunar eclipses can be seen by a record number of people at the same time, solar eclipses sometimes happen where only a few people can spot them.

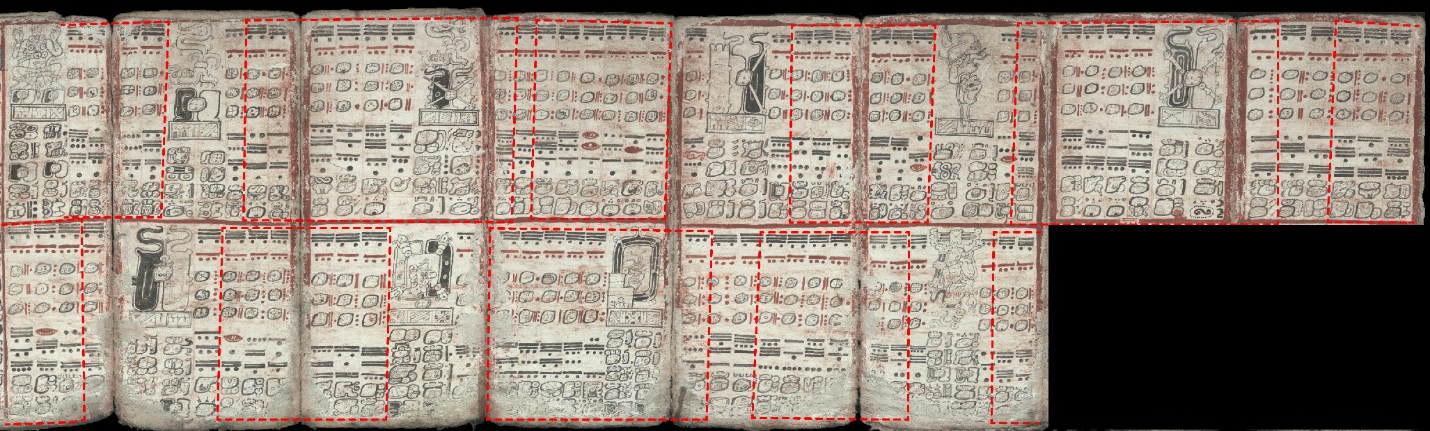

The full eclipse table of the Dresden Codex.

Image courtesy of J. Justeson

An issue emerges, though. If you were to take the lunar calendar table as it is, its eclipse predictive ability will get worse and worse after a few cycles. But the “daykeepers”, the Maya calendar specialists, learned to reset the lunar calendar table at specific intervals.

“What I figured out was that there were two spots in the table that were closest to the exact alignment of the Earth, Moon, and Sun, which would be the date of an eclipse. One of them at 358 months with an error of a tiny fraction of a day. There was another one at 223 months that had about four times as large an error,” lead author Professor John Justeson told IFLScience.

The 358 and 223 might seem like two other random numbers, but they are not. Both of them represent eclipse cycles. The inex cycle takes 358 synodic months, while the saros cycle takes 223 synodic months. Resetting the lunar calendar using those two specific points would allow the predictions to be accurate for hundreds of years.

The researchers suggested that the calendar was designed most likely for the years 1083-1116 or 1116-1140 CE, so it could have possibly worked to predict all the eclipses to this day, including the two crossing Mexico in recent years.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

Source Link: The Maya Calendar Had A Way To Predict Eclipses That Was Accurate For Centuries