A team of physicists has outlined a possible way of sending probes deep into interstellar space within a reasonable timescale, using relativistic electron beams.

Space is that annoying combination of “really cool” and “really big”. We can see really awesome stuff going on out there, but unless we come up with ways to significantly improve our propulsion methods, we aren’t going to be taking a look at them any time soon.

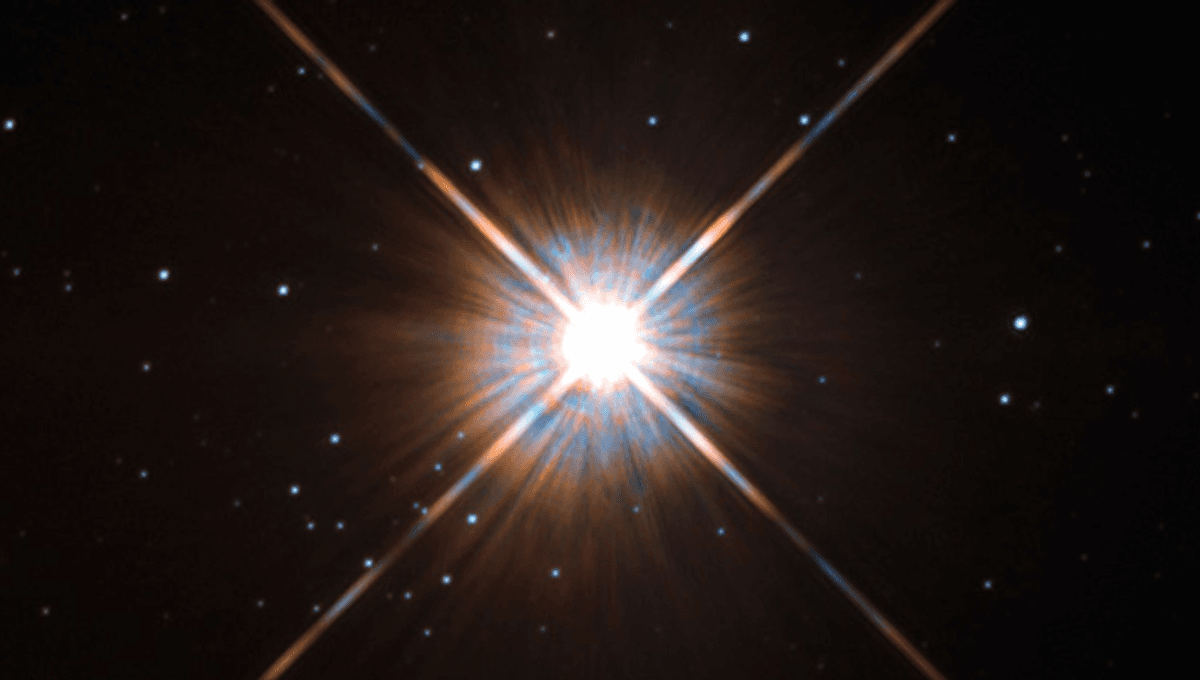

Traveling at the speed of Voyager, it would take over 73,000 years to reach our nearest star, Proxima Centauri. Even if we had solid evidence of life on Proxima Centauri b – the planet discovered in Proxima Centauri’s habitable zone – it would be tough to persuade someone to commit their ancestors to travel through space on a generation ship for longer than it took humanity to go from just a few thousand people to 7.674 billion.

In 2016, the long-term project Breakthrough Starshot was set up to figure out a way that we could do the next best thing; send a probe to the Alpha Centauri system, potentially to photograph it before returning to Earth.

Early designs, which rely on components getting small and light enough to propel with relative ease, proposed that scientists could propel the small craft using a light sail and a directed laser, while later suggestions have involved firing elementary particles or microwaves at the probe. The problem with these ideas, according to the new paper, is that the cost of running the source beam is very high, and it is difficult to prevent the beam from spreading out, making it inefficient. Equally irritating is the fact that the further away from the source beam, the less power you can transfer to it.

“A current project, Breakthrough Starshot, envisions beam ranges on the order of 0.1 AU from a very large laser array that directly pushes on light sails. Using the energy of the beam to expel reaction mass from the vehicle requires less power for a given thrust than using the beam momentum directly for missions where the total velocity change is much less than the beam velocity,” the team explains in their paper. “However, neither mode of operation fundamentally changes the tradeoff requirements for beams.”

Attempting to work around this problem, the team suggested alternative methods of accelerating crafts using a solar sail using electrons accelerated to relativistic speeds. At these speeds they can experience a “relativistic pinch”, an effect well-studied in particle accelerator and beam physics, which the team believes would help stop the spreading problem.

“In the frame of reference co-moving with the electron beam, this can be thought of as relativistic time dilation; there is not enough time in the beam frame for the space charge to spread the beam very far,” the team explains. “Or, in a frame of reference at rest with respect to the Sun, one can think of these as relativistic increases in the electron momentum effectively reducing the charge-to-mass ratio of the electrons, again slowing the spread of the beam.”

Accelerating the beam up to relativistic speeds, and keeping it directed at the target probe, would be somewhat of a challenge, and is still not something that will take place any time soon. The team suggests that the most promising idea is a “solar statite”, or a hypothetical craft that uses its own solar sail to modify its orbit of the Sun. With this maneuverability, it could have a continuous view of the probe it is directing the beam at. Using this method, we could potentially reduce travel time to decades, rather than millennia.

Though this could potentially make the project feasible without too many advancements, some will still be necessary before we can send a probe to our nearest stars, and potentially habitable planets.

“By using thermoelectric conversion in a near-solar statite, large, GW-class beam infrastructure can potentially be launched in the near term without waiting for the industrialization of near-Earth space,” the team concludes. “However, the usefulness of this approach depends on the discovery of a high-specific-power means of reception and conversion of that energy, either as beamed momentum or to eject reaction mass or push on the interplanetary medium as reaction mass.”

The study is published in the journal Acta Astronautica.

Source Link: We Could Send A Spacecraft To Our Closest Stars With Electron Beams, Physicists Suggest