It’s the Late Cretaceous and you, an ankylosaur, have been minding your own business while eating some plants. You’re famished from bashing away Tyrannosaurus rex all day – those pesky predators – and now some other ankylosaur is moving in on your patch. Time to dust off that tail, because it’s clubbing time.

That’s the picture painted by new research from scientists at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Royal BC Museum, and North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences who have found evidence that suggests ankylosaurs used their armored tails for social dominance, as well as self-defense. The finding comes from investigations into a Zuul crurivastator fossil, which demonstrates spikes along its flanks that were shattered and healed while the animal was alive.

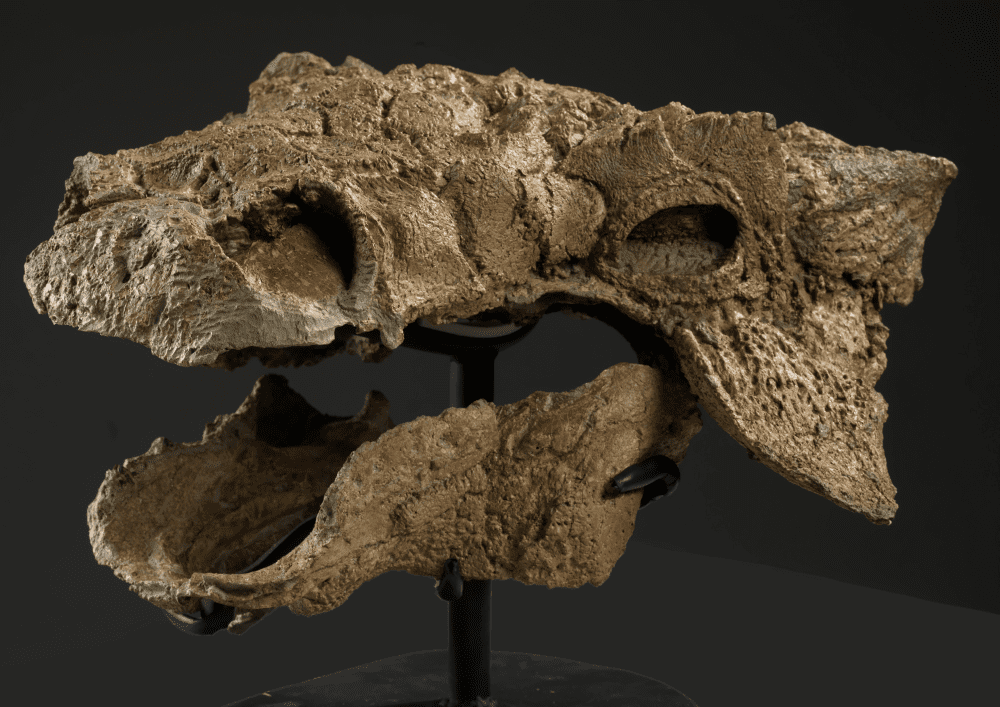

No ankylosaur, only Zuul. Image credit: Royal Ontario Museum

In case you’re thinking Zuul crurivastator is a very cool species name, you’d be right. It was taken from the fictional monster “Zuul” from Ghostbusters, and Latin for “the destroyer of shins”. Razor scooters got nothing on the bony-blobbed sledgehammer that was the tip of Zuul’s tail.

What’s curious about the injury is that it looks like it was inflicted by a fellow ankylosaur, indicating these animals were fighting each other as much as they were battling with predators.

“I’ve been interested in how ankylosaurs used their tail clubs for years and this is a really exciting new piece of the puzzle,” said lead author Dr. Victoria Arbour, Curator of Palaeontology at the Royal BC Museum and former NSERC postdoctoral fellow at the Royal Ontario Museum, in a statement.

An undamaged armored spike on Zuul. Image credit: Royal Ontario Museum

“We know that ankylosaurs could use their tail clubs to deliver very strong blows to an opponent, but most people thought they were using their tail clubs to fight predators. Instead, ankylosaurs like Zuul may have been fighting each other.”

Barbaric as communicating through tail smacks might sound to the humble Homo sapiens, this kind of social interaction is a complex behavior. It indicates that these ancient animals may have been fighting it out to protect their patch, or perhaps participating in their own brand of “rutting” season as males competed to win a mate.

Zuul’s complex behavior was discovered thanks to painstaking work that freed the fossil from 15,876 kilograms (35,000 pounds) of sandstone. Doing so uncovered preserved skin and bony armor that showed it was covered in bony plates, the spikiest of which lined its flanks.

The flattened spike of Zuul, indicating it was well-worn in life. Image credit: Royal Ontario Museum

A closer looked showed there was a curious pattern of spikes missing their tips, showing signs of healing from apparent repeated injury. The pattern told researchers that they were more likely the result of ritualized combat than sporadic attacks from a predator.

“The fact that the skin and armour are preserved in place is like a snapshot of how Zuul looked when it was alive,” said Dr. David Evans, Temerty Chair and Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum. “And the injuries Zuul sustained during its lifetime tell us about how it may have behaved and interacted with other animals in its ancient environment.”

The study was published in Biology Letters.

Source Link: Zuul Used Its Weaponized Rear-End For Social Dominance As Well As Clubbing T. Rex