Let’s start with a point a few people may not like. The Bible, the collection of texts that make up the holy book for Christians across the world, was not created in the state we have it today. The whole thing is a compilation of different narratives, instructions, prophecies, and poems written by different people over hundreds of years. More significantly, the texts that now exist in the document were themselves selected from various other competing texts by humans, rather than divine agency.

A popular misconception

The Bible has a history, and it is a complicated one. This may not surprise anyone who has read Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, which became popular in 2003. According to Brown’s fictional (and historically dubious) narrative, the books that make up the Bible were officially selected and put together by the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, under the authority of Constantine I who sought to define Christian doctrine and belief.

Although the Council certainly did meet at a time of crisis within the Church, it did not address the biblical canon, despite what Brown said. This has become a modern myth that has outlasted the book’s initial surge in popularity. In reality, the Council of Nicaea met to debate the nature of the Trinity (that Jesus is the son, and father, and the holy spirit at the same time), among other things.

So, who decided which books ended up in the Bible? Ultimately, no single person or group of people decided it. Instead, the Bible as we know it (and this is itself a tricky point, as the book’s compilation varies between denominations) was reviewed and changed at various times over a much longer period.

Establishing the book

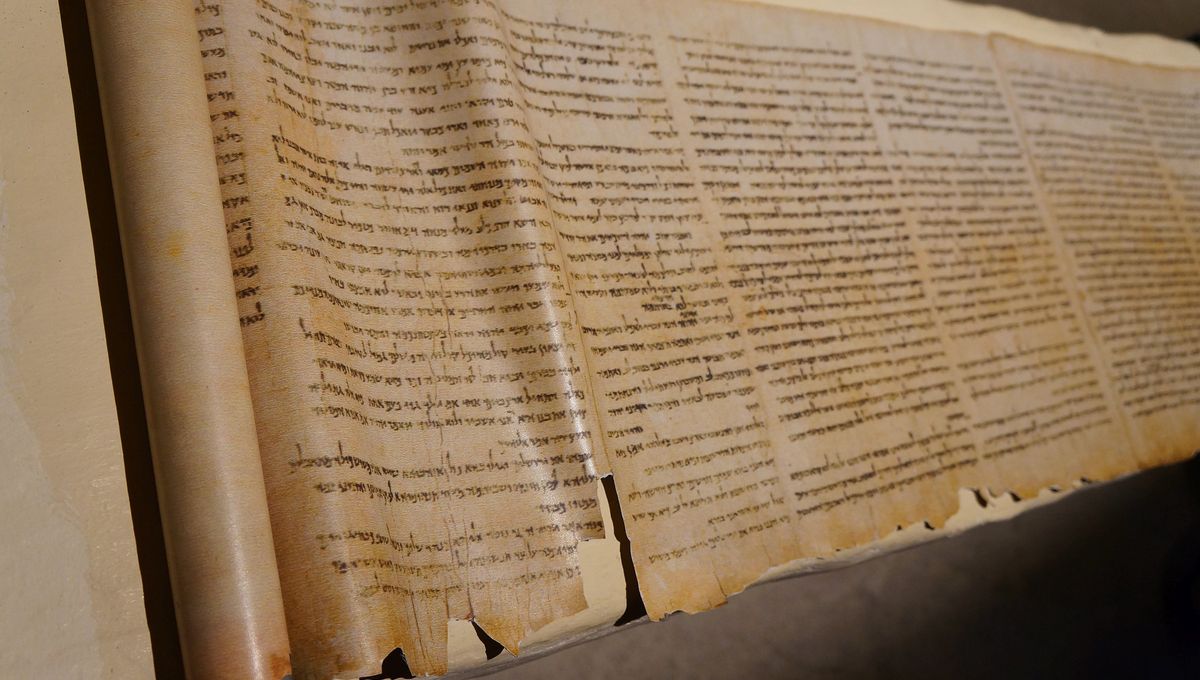

It’s important to remember that books themselves, holy or otherwise, have histories. Prior to the invention of the printing press around the 1440s, a book had to be made by hand. It was a slow and laborious process. But before this, the texts that made up the Bible were stored on individual handwritten scrolls (none of the original copies survive to this day).

Throughout the first to fourth century CE, and beyond, various Church authorities and scholars argued about scripture and which texts should be included in the canon. In most instances, they cast their opponents as heretics if they did not agree with them.

In this game, the loudest and most influential voices won the day and over time the books (scrolls) deemed to be authoritative and authentic by those who used them were added to the canon. Those that did not make the cut were discarded.

Although much of this process was completed by the end of the fourth century CE, debates over the Bible’s texts continued into the 16th century when Martin Luther published his German Bible, the first vernacular translation of the Christian scriptures.

What about the rejected texts?

There are many books that were rejected from what we understand to be the Old and New Testaments today. Although not all of them have survived, we know they existed because they were included in various lists circulated among the followers of the early Church. They include the Didache (or Teaching of the Twelve Apostles), the Shepherd of Hermas, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Epistle of Barnabas, and the Epistle of Clement. There were others too (including banned books that did not make the cut).

It is worth noting here that many of these texts were not rejected because they contained some secret knowledge, occult principle or some such. They were simply judged to be less authoritative or lacking spiritual substance.

Source Link: Who Decided Which Books Went Into The Bible?