Is your hair lacking volume, are you feeling less than perfect? Well, maybe you should try adding some lizard to your shampoo. This may sound like a new TikTok trend (or maybe this will start one), but it’s actually part of a set medieval medical recipes recently discovered by scholars that redefine our assumptions of medicine during the Middle Ages.

The project, which was led by the University of St Andrews, Scotland, in collaboration with other institutes in Europe and America, sought to establish a new catalog of Latin medical manuscripts from the early medieval period. In particular, they wanted to gather medical texts created before what is known as the Salerno School revolution of the 11th century, which revived the tradition of ancient schools that taught “formal” medicine.

According to the traditional story, after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century CE, Europe experienced the so called “Dark Ages” whereby classical knowledge was lost until it was rediscovered in the 10th century CE. It was essentially characterized as a step back in scientific and rational progresses, especially when you compared the achievements of the Roman Empire – its infrastructure, medicine, and engineering – to the situation of this period.

The idea of the “Dark Ages” was popularized in the Renaissance and was later perpetuated by Enlightenment thinkers. However, modern historians of science and medicine largely reject the term for being inaccurate, too simplistic, and very much Western European centric. Indeed, while Europeans may have lost much of the Classical world, the Islamic world was intellectually thriving, developing innovations in medicine, mathematics, optics, and astronomy.

The term “Dark Ages” is also extremely value-laden, casting Western Europe as “backwards” and ignorant, rather than seeing it as a period of complex change. And this is a point powerfully challenged by the Corpus of Early Medieval Latin Medicine project, which has now identified hundreds of medical manuscripts from this period.

Far from being ignorant of Classical knowledge, the newly identified manuscripts demonstrate that early medieval monks did engage with authoritative non-Christian work.

Image credit: KBR, Brussels

Contrary to the popular belief, the research has shown that early medieval people were hugely interested in collecting cures and sharing authoritative health advice. At the same time, the texts they have gathered demonstrate that medieval Christians actually engage with and adopted insights from non-Christian ancient Greek medicine in order to understand the rational structures of nature.

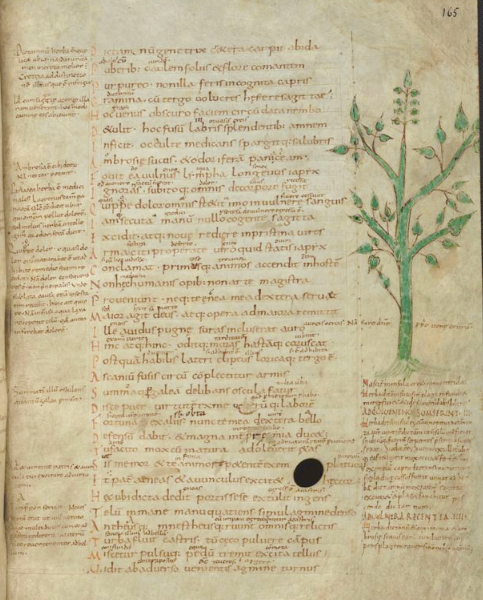

Much of this information has been available for a long time, but it has been overlooked by scholars because it is transmitted in manuscripts that contain non-medical works, such as those on theology, grammar, and science. Often they were copied in the margins or simply on blank pages.

Interestingly, it seems many medical recipes actually included exotic herbs and spices that would have had to travel thousands of miles to reach Europe. For instance, things like cloves or black pepper would have come from as far away as Indonesia, while cinnamon came from Sri Lanka, and cumin and saffron from Persia. Their inclusion in these European texts indicates a lively long-distance trade network that extended from Europe into Africa and Asia, indicating just how connected the medieval world really was.

And if you ever needed a reminder that people from the ancient world were not that different from us today, you can see entertaining (or depressing, depending on your perspective) parallels between some of the content and today’s social media wellness influencers. For instance, there was a sustained interest in seasonal healthcare and dietary regimes to prevent illness, many of which required a disciplined lifestyle as the best way to stay healthy.

They also promoted moderacy in all things and only eating seasonal food and the use of herbal potions that were effectively “cure all’s” for every ailment. And of course, they would also reduce toxins (can’t forget about those toxins).

Many of these works were copied by monks, which makes some of their content quite surprising. The above mentioned “lizard shampoo” is one thing, but it seems some non-Christian works, like the prognostic texts known as the “Sphere of Pythagoras” were also popular. This text was used to predict the outcomes of illness or to indicate the sex of a baby.

“It shows us that, in what was supposed to be a dark age for medical knowledge, there was huge interest in collecting cures and sharing authoritative health advice,” Professor James Palmer from the School of History at the University of St Andrews said in a statement.

“Moreover, we have been able to show medieval Christians adopting insights from non-Christian ancient Greek medicine to understand the rational structures of nature.”

“One of the main findings was that medical knowledge got everywhere, with recipes and other texts jotted down in books on theology, natural science or language. It shows people were curious about medicine and collected all sorts of things that might be useful, from ancient works by Hippocrates and Galen, to local traditional wisdom. It’s a long way from the classic image of the Church rejecting medicine while people wallowed in superstition.”

The team hope the project will demonstrate the early medieval period in a more positive light, foregrounding people’s curiosity and their thirst for knowledge.

The results will be made into a book to make the findings accessible to a broader audience and they plan to publish editions and translations of some of the texts for future researchers.

Source Link: "Lizard Shampoo" And Pagan Texts Suggest "Dark Age" Medicine Wasn't So Dark After All