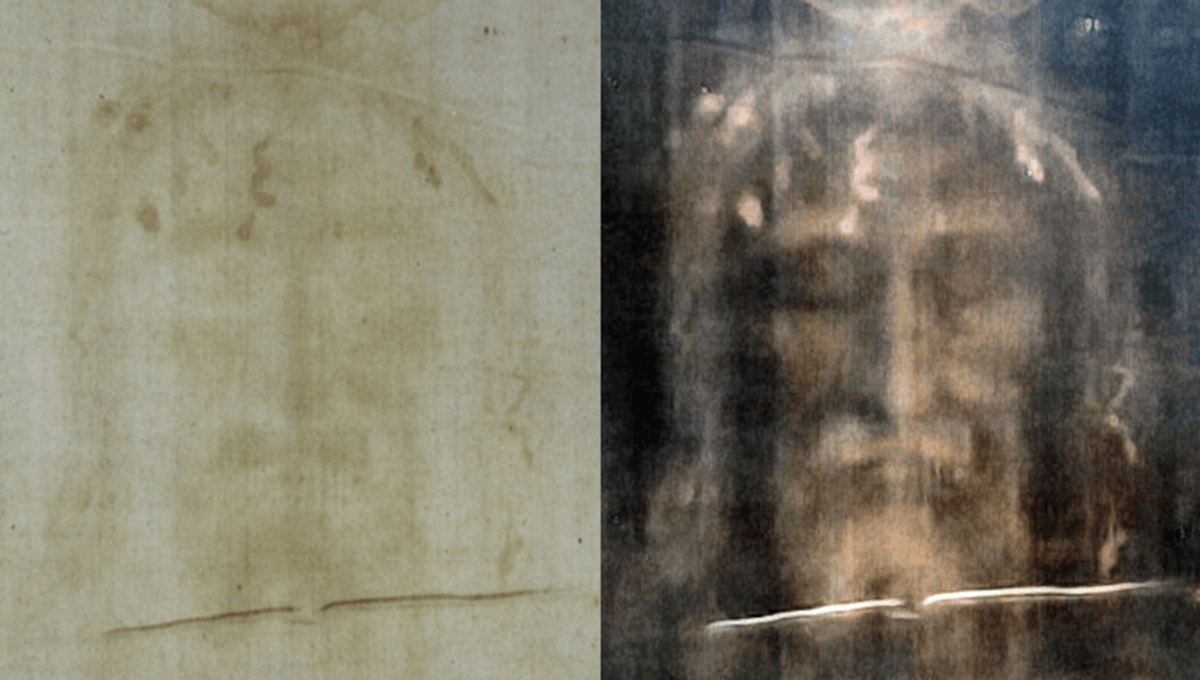

The shroud of Turin is a large piece of linen cloth that was used to wrap the body of Jesus Christ, according to those who believe in it. The cloth contains a faint image, which people have claimed shows the face of Jesus of Nazareth himself, complete with a crown of thorns and stains which people believe to be blood.

As with other supposed relics relating to Jesus, its authenticity has been heavily disputed. The first historical record we have of it was in 1354, belonging to Knight Templar Geoffroi de Charnay. Thirty-five years later it went on exhibition, where it was labeled a fraud by the bishop of Troyes who called it “cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who painted it”.

Nevertheless, popes through the years have believed in its authenticity and made pilgrimages to it as late as 2015. The shroud is rarely displayed today but has been submitted to scientific testing, in an attempt to determine precisely when and where it was made, and by who.

In the 1980s, the shroud was submitted to radiocarbon dating, along with three control samples, by three separate teams of scientists, each working independently.

“The results of radiocarbon measurements at Arizona, Oxford and Zurich yield a calibrated calendar age range with at least 95 percent confidence for the linen of the Shroud of Turin of [CE] 1260-1390,” a paper on the tests published in Nature concludes.

“These results therefore provide conclusive evidence that the linen of the Shroud of Turin is medieval.”

This dates it roughly to around the time it appeared in historical records, near to the time when the bishop of Troyes declared it to be a cunning fraud. It has since been suggested, by those who likely want to believe in its authenticity, that the teams could have taken a sample from an area of the shroud which was repaired in the 12-1300s, or that the shroud was contaminated during a fire in Chambery, France, in 1532.

Clutching even more desperately at straws, others have suggested that the shroud became contaminated by carbon monoxide, throwing off the dating of the cloth by a thousand or so years. Subjecting other cloths to carbon monoxide as a test, however, has not shown any significant impact on radiocarbon dating.

Other studies have focused on the patterns on the shroud itself. One team, using a mannequin and a volunteer, simulated wounds as shown on the shroud using real and synthetic blood. Blood was pumped around the mannequin, and released at the wound points supposedly shown on the shroud, which was then left to flow to show researchers what the resulting patterns would look like.

The team had been hoping to determine whether the patterns were consistent with a T-shaped crucifix or a Y-shaped crucifix, but concluded that they were not consistent with crucifixion at all. The body parts would have had to have been at different angles to produce the patterns seen on the shroud.

Though this analysis has also been questioned – by people saying it could have been altered if a body had been transported inside the linen, for example – the scientific evidence so far tells a simple story.

“The simplest, albeit the dullest, conclusion to reach,” as one team put it, “is that the shroud’s age is its historic age”. At some point before the shroud entered historical records in the 1300s, it was forged.

Source Link: What Scientists Found When They Studied The Shroud Of Turin